-

Posts

39 -

Joined

-

Last visited

Posts posted by aawoods

-

-

I confess, I'm not much one for romance novels. My few early introductions into the genre were bodice rippers featuring Fabio's bulging pectoral muscles and a woman swooning beneath a bold-face title. Needless to say, I ended up squarely in the science fiction and fantasy genre, where at the very least the covers were more discrete.

I confess, I'm not much one for romance novels. My few early introductions into the genre were bodice rippers featuring Fabio's bulging pectoral muscles and a woman swooning beneath a bold-face title. Needless to say, I ended up squarely in the science fiction and fantasy genre, where at the very least the covers were more discrete.

However, in the age of Kindle and cheerful cartoon cover designs, I decided to take another gander at what's going on in Romancelandia and check out Evie Dunmore's debut bestseller, Bringing Down the Duke. I am pleased to report that, while there was some bodice-ripping-adjacent shenanigans going on, I found this novel to be both highly enjoyable and highly educational from a craft perspective.

The crux of any romance novel is, of course, the characters. Everything in the story hinges around the chemistry between the two love interests. Dress it up in whatever sub-genre flair you want, proper romance must get those to lovebirds right. And this story does exactly that. The protagonist of the story is the sassy and bold suffragette Annabelle, whose situation is dire as she struggles to make ends meet and make her mark as one of Oxford's very first female students. Her love interest is the serious, duty-driven Sebastian, Duke of Montgomery. I was impressed by how much Dunmore nailed the opposites-attract, enemies-to-lovers story arc, where the two protagonists were perfectly situated to both hate and also challenge/fascinate each other. They start off the story on opposite sides of the suffragette movement, not to mention polar different ends of the class spectrum, which creates tension right off the bat. Right away, there is tons of story conflict to mine, especially when the characters are forced together because of deftly plotted circumstance. Dunmore, of course, doesn't leave it at that. She also adds in the tension of Annabelle's situation, desperate for money and tied into a movement that could put her whole education at risk, along with some great backstory about the Duke's family troubles, strained sibling relationship, and mysterious tragic backstory.

Of course, Annabelle and Sebastian quickly fall in love, circling one another like planets aligning. And this is where Dunmore's debut novel really knocks it out of the park [SPOILER ALERT]. One of the issues with Romance is how to keep characters apart when they're clearly destined to be together, which leads to a lot of contrived twists and eye-rolling miscommunications. See, you have to fill a whole novel with story—which means the two love interests can't just fall in love and be happy—while simultaneously not making either of them dumb, cruel, or otherwise unlikable. This novel expertly wields history for plot purposes, using the fact that a Duke couldn't marry a commoner without a scandal that would cost Montgomery the family castle he's been working to get back from the Queen. It's his life's work and ambition to reacquire what his gambling father lost, and openly tying himself to Annabelle would mean sacrificing that dream. And while there is the option that Annabelle could be his mistress, her own specific personal history makes that option impossible (not to mention dis-empowering!).

Like all good romance novels, this one has the mandatory HEA (Happily Ever After). It also has some really excellent discussions about women's rights, various schools of philosophy, and classism. As I've mentioned before, those details elevate an already good story to bestseller status. But the real backbone of this book is the fun roller coaster drama of lovable, in-love characters navigating the interesting setting of 1879 England. Dunmore created two fully fleshed-out people who were destined to be together, and the story of how they get there is un-put-downable.

Are you a romance writer? If so, I recommend studying Bringing Down the Duke. It's fun, funny, clever, and a must-read for anyone trying their hand at the biggest book genre in the world. If you're anything like Evie Dunmore, then hats off, because good things are coming your way.

-

I thought this pretty solid advice! It's a bit of a rambly video and could have been done in a more condensed fashion, but her tips were a great place to start for a new writer. No complaints from me on this one. I suppose if I had to gripe, I'd say it's pretty common sense stuff.

I did like her point about making sure you're learning from good people, since bad writing advice seems to perpetuate on the internet ad infinitum. We are obviously the good people here

-

I agree with Michael, this was distractingly theatrical. Kind of ponderous and self-important, to be honest.

I think telling writers to be "honest" is the same as saying that they need to find their "voice," which is a true statement but not altogether useful for the writer learning their craft. Those sort of meta-skills just come from repetition, practice, and listening to feedback, and isn't something one can just wake up and start doing.

The one useful piece of advice in here is to read like a writer, not like a reader. I agree with that, where if you're serious about the writing craft you should be picking apart the stories you enjoy (or don't!) to understand what makes them tick. I certainly understand the temptation to just fall into novels the way I used to, but it takes that extra bit of mental effort to dig beneath the surface and see the puzzle pieces that make a story successful.

Also, I do love the quote that to be a writer, you must do the equivalent of walking down the street naked. It's not useful for craft advice, but I've found that the more I write, the more of myself I put into my books which can be uncomfortable. I think King also said something along the lines that "if you want to be a writer, your days in polite society are numbered," which feels like much the same sentiment. Basically, it's writing fearlessly and truthfully about the world, telling stories about humans as they actually are. This is true for any genre, where the story dressings and world-building depend on the people being believable and relatable. I suppose that could be called being honest.

In the end, perhaps it was Gaiman finding his voice and being authentic, as Kara says, that made him successful. But maybe it was that he just got better over time and learned the skills to convey realistic stories.

-

Good points Michael!

You’re totally right on the originality of ideas. I was speaking in terms of archetypal stories (eg the hero’s journey) which have been done, but of course can be remade into endless new varieties, both high concept and not. Perhaps the way to charitably interpret her blunt advice is to embrace the creative remaking of old ideas and don’t waste time trying to reinvent the wheel? Familiar yet different is, after all, the root of most high concept stories.

I agree though, this video did feel like it had a very specific axe to grind. More of a rant than constructive writing tips.

-

Oh dear, I think this will show how cynical I've become...

I'll agree with Kara and Joe that she's pretty unpleasant and shrill in her delivery. I wouldn't recommend this video for that reason alone. But, at the risk of being the debbie downer of the group, I wouldn't necessarily disagree with her points.

In my previous pre-med career, I had a physician tell me that if a person can be talked out of being a doctor, then they should be, because they won't have the fortitude to make it. Alas, I would apply the same advice to writing as a profession.

Now, if you're writing as a hobby, then all the power to you. Have fun with it, don't watch videos like these, and don't let the naysayers ruin a perfectly good time. After all, I can play tennis without ever making plans to go to Wimbledon.

But yeah, pro writing is tough. It's a brutal industry, full of cold rejection and constant failure. Your first novel probably will suck, and she's right, very few people will care as much about your work and career as you do. Even the process of writing itself can be agonizing (I'm highly suspicious of those who say writing doesn't feel like work because it's just so fun. If that's true, I hope they step on a Lego). She's right that almost nothing is original. She's right that the publishing field is a business, and that the inevitable rejections you'll get aren't personal. She's right (at least in my experience) that there isn't as much money in publishing as people like to believe. Books, especially novels, are not a way to be a millionaire except for the anointed few.

And she is very right, I think, that you need a reason beyond money or fame to keep you going. Because the awful, ugly, slimy truth that none of us like to look directly at is that writing is a gamble. There are no guarantees. You're spending your precious life doing something that may or may not ever pay the electrical bill. I sincerely hope it will, for all of us, and please keep fantasizing about that big-5 deal! I sure do. But I also recommend acknowledging the possibility that it might not work out. So why do it? Personally, I get cosmic satisfaction from the cycle of improvement I associate with the writing craft. I like getting better. I like finishing things. And I love entertaining people. The intermittent highs of happy readers keep me writing, even when it's dismal.

But if I was only in this for external rewards like money or fame, I'd have burnt out long ago. And (don't hate me for saying it) that would have been a good thing.

There's my share of tough love for the day! I'll retreat to my dark little corner now, haha.

-

In the context of NaNoWriMo, I find this video to be a useful kickstarter for new writers looking to figure out how they're going to start page one. I especially like the idea of "types of progress" whether it be through information, physical movement, etc. While I do think Sanderson's "Promise, Progress toward that promise, and Payoff" structure is quite a bit oversimplified... [SEE BELOW]

-

So I'll admit, I'm kind of a Green brothers fan. I find their YouTube channel charming and escapist. I also unabashedly loved The Fault in our Stars. It's like a melodramatic Titanic for teenagers and I was there for it.

That said, I agree with Joe that this video might do more harm than good when it comes to giving writers advice. It sounds like Hank is (as we've been hammering on so hard here) a panster. From the way he described his process, it sounds like he sort of wanders through the story and sees where his interest (and the characters) take him. He's right that novels take time, but I think he's wrong in thinking novels must take quite so much time. If the story is well-constructed, it doesn't need to take that long. If the characters are fleshed out and understood in advance, then they shouldn't deviate from a plot that's been built around them. Heavy revisions and/or writer's block come, in my experience, from subpar planning. That's an avoidable problem, if a writer is willing to put in the work.

Which brings me to the point Joe also made, that his "all of these are writing" list is a lot more generous than I'd allow. Brainstorming key scenes, constructing an outline, and fleshing out story-specific world details? Yes, those could perhaps be considered "writing." But reading other people's books? Reading your own work (in a way that isn't editing)? Staring off into the distance and letting your mind aimlessly meander? Wikipedia rabbit-holes about things tangentially related to your story? No, I'm afraid those don't count as writing. Maybe, as Elise pointed out, they can count as supplemental study, or important background work. But I'd hesitate to give myself credit for something that isn't butt-in-chair, words-on-page time. Again, I come back to the fact that this is a job, and if an imaginary boss was paying you hourly to write, what would that person consider job-relevant? It's an unromantic way to think about it, but a little pragmatism goes a long way in this biz. Be an artist, but drop the starving part.

Elise is right though, he is entertaining

-

If you can write an excellent heist story, I can all but guarantee that fame and fortune will come knocking on your door. Everyone, and I mean everyone loves a well-constructed caper. Oceans 11, The Italian Job, The Thomas Crown Affair, The Lies of Locke Lamora, Mistborn, etc. The list goes on and on. As consumers of fiction, we love the feeling of the story shifting beneath our feet, of being outsmarted but reveling in the fact that we could have figured it out if we'd only been clever enough. Everyone knows the joy of a good twist, or a great mystery, and heist novels are chock full of both.

If you can write an excellent heist story, I can all but guarantee that fame and fortune will come knocking on your door. Everyone, and I mean everyone loves a well-constructed caper. Oceans 11, The Italian Job, The Thomas Crown Affair, The Lies of Locke Lamora, Mistborn, etc. The list goes on and on. As consumers of fiction, we love the feeling of the story shifting beneath our feet, of being outsmarted but reveling in the fact that we could have figured it out if we'd only been clever enough. Everyone knows the joy of a good twist, or a great mystery, and heist novels are chock full of both.

Writers beware: it's one of the more difficult plot-lines to pull off, right up there with time-travel and unreliable narrators.

But when done well, the industry adores it.

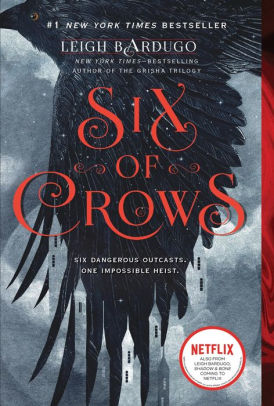

For a recent example of this phenomenon, look no further than Leigh Bardugo's breakout bestseller, Six of Crows. On the surface, this is a pretty typical YA fantasy. It features six point-of-view characters, all teenagers, all suffering from various romantic and interpersonal angsts. However, the thing that makes Six of Crows stand out in the crowded YA fantasy field is that the story centers around a high-stakes, high-concept, epic and death-defying, you-know-where-I'm-going-with this... heist.

I won't go into the brilliant details of the theft itself here. To do so would take ages, not to mention spoil the bulk of the novel. But there are a few things that we novelists can learn from the clockwork construction that makes Six of Crows tick.

First: The characters. Every single character in the story has a specific purpose, use, and arc that's story-critical. Even though there are six—six!—protagonists, Bardugo finds a way to make each of them matter. They all have a specialty that's utterly necessary to pull off the grand plot, not to mention a character trajectory that's important and meaningful. This makes the reader feel like the author knows what they're doing, that nothing is superfluous. The novel is a machine, well-built and expertly finessed.

Second: The stakes. Any writer who's spent time on this website can't deny the importance of big stakes. There needs to be a reason for the story, especially a story about thieves, beyond simple enrichment or fame-seeking. Six of Crows makes the heist matter to the characters, and so the reader, by making the object of the heist an addictive magical drug that would radically shift the balance of power in Bardugo's world. This makes the heist important on the grand scale, but Bardugo goes further than that. The heist also matters on an interpersonal level, in specific ways to each of the characters. It's about more than money. Bardugo does the work to make the reader first care about the people and then care about why they must do this. And so the reader is hooked into...

Third: The twists. Now, it's easy to understand the foundation of a well-built heist novel (although very, very difficult to actually build one). It needs to be intricate, surprising, and clever. The leader of the team must be smarter than the reader, the mark, and, quite possibly, the writer themselves. Not easy to do. But the real challenge of a heist novel is to not make it easy. This brilliant mastermind must construct a genius plan that fails, at least in some way. This is where so many writers drop the ball. The gimmick of Sherlock Holmes being all-knowing is fun for about 10 minutes, but the story of Sherlock Holmes only happens when he's outwitted, or distracted, or surprised. If your mastermind is smart, then the antagonist must be smarter. Only then can you show the true genius of the heist's grand master, when their equally-brilliant, even-more-daring plan B must come into effect, or perhaps when they come up with something genius on the fly. Then and only then can the reader/watcher see the true power of the heroic team, overcoming a real, tangible obstacle that threatened real, tangible failure.

Make it tough, and the readers will be scrabbling for more.

Six of Crows is not without faults. It suffers from a saggy, meandering middle between the first plot point and when the mischief actually begins. It's also bogged down, as many YA books are, by an overabundance of adolescent hormones. Worst of all, the much-anticipated sequel was, to put it mildly, a disappointment. But all that can be forgiven because the theft itself is so excellently constructed. The caper fits into the world, brings together all the pieces of the story, is compulsively readable, charming, and (almost entirely) satisfying. It's a fun book to enjoy and an important book to study for anyone brave enough to take on the mantle of such a twist-heavy genre.

So go forth and write crime! Who knows? You might find story gold along the way.

Or perhaps steal some...

-

I second Kara and Joe in that this one is positive and kindly meant. I think it's a fine "absolute baseline beginner" video in the sense that it's motivational, with a sweet, sort of fluffy undertone. After all, no one wants to hear when they're first starting that "this industry is brutal as all hell, you should brace yourself for the worst or jump ship now."

However, I also think Michael is right. Her advice is amateurish and too vague and soft to really be helpful. I also do not think that every idea is a good one - there are ideas that, when pursued, lead only to wasted manuscripts (I myself have written upwards of 5 of them and do wish I'd spent that time more wisely). I do NOT recommend experimenting with pantsing if you're a natural plotter. Plotting is far, far easier to succeed at in genre writing. I would wager if someone did a study on the top 1000 writers in the world, between 90 and 99% of them would be plotters. So don't step back from your natural strengths if you're a person drawn to outlines. When writing commercial fiction, that's a plus, not a hindrance.

I also think her ideas about motivation, while good, aren't as blunt as I think professionals would be. At the end of the day writing is a job. You do your job if you want to get paid. That's it. Yes, it's also an art and there's a certain level of intrinsic difficulty in creating art, and pushing past mental blocks. But if you want to be a professional writer, then you need to learn to write like one.

I'll end with a note about her comments on editing. The breakdown of editing here is correct (developmental edit to line edit to proofreading), but there are some HUGE things she leaves out. It seems like an enormous emission not to mention beta readers or critique partners, since literally no writer ever can go from idea to finished novel by their lonesome. Some grammar-savvy authors MIGHT be able to proofread themselves, but trust me, you can't see all the flaws in your own book. The more eyes on the manuscript, the better. She is correct (but doesn't emphasize enough) that, if you're self-publishing, you MUST hire a professional editor. It's even becoming recommended in some traditional publishing circles, to either hire a pro or have several round of betas to make sure that book is in tip-top shape before it goes out to agents. There's mixed advice on whether or not you need to pay someone for editing services before querying, but in a field that's more competitive than ever, writers must do everything in their power to get their books into the best shape imaginable.

All in all, I thought this was a sort of vague, sweet instructional from someone who means well, but isn't, at the end of the day, a pro. I admire her positivity and motivational sentiment, but I think true writing advice for those who really want to reach success in the field requires a bit more roughage.

Although to be fair, after 6 years and 15+ novels, I might just be a lot more jaded...

-

On 1/26/2021 at 5:14 PM, MichaelNeff said:

If Sarah and Conner are racing to Jupiter, a diversion to the casino planet for three chapters worth of blackjack might not work (this actually happened in a screenplay collaboration).

Sounds similar a certain Star Wars movie that was notoriously ill-received....

For the record, I agree that some plotting is inevitable. Even so-called "pansters" must have the general arc in mind, or at least the preexisting twists for a satisfying story, right? How else would Martin have planned the *SPOILERS AHEAD* Hodor scene, or the reveals of various character heritages, or the end-goal of Dany's descent into madness? As much as Martin, like King, talks about eschewing plot for natural character development, in some ways those characters are still on tracks that stem from their backstories. Is that not plot?

As Michael points out, King proves this in the above statement, where the idea itself had a natural inciting incident, first plot point, climax, etc. Perhaps he didn't intentionally plan or name it that way, but as a good story it needed those elements, so he crafted them.

Personally, I think the whole plotting/pansting debate has been badly framed in writing circles. I think it breaks down to the writers who follow the broad strokes, in their head, in some kind of "instinctual" way, often using the rough draft as a sort of playground/idea garden on which to base the entirely-rewritten second draft (as Kara says, knowing points A and B and C, but not the details between them), and, on the other hand, writers who carefully craft outlines first, then write first drafts, and then edit said drafts that don't (usually) have to be entirely scrapped. Either way, there's inherent planning in the story and an inevitable climax it must build to. Some writers just keep that part more vague than others.

Thoughts?

-

There's some good in here....and some not-so-good.

He's totally right that "the best writers are voracious readers", and no writer ever succeeds without getting REAL comfortable with rejection. You should, in fact, hone your writing with imitation exercises/short stories, have a routine, and pick the best possible ideas to work on.

And every writer should strive to be a King, not a Martin, when it comes to productivity.

But going where the story leads you? Now this is the real stinker because, sir or ma'am, that's risking a whole lot of time, words, and creative agony on the fact that you might not have the natural talent of Stephen King. Are you willing to track through hundreds of pages to see if you've got the right 'instinct'? Are you willing to rewrite the whole darn thing because you didn't truly think through this plot thread or that character arc?

Wouldn't it be easier to plan out a hard-hitting, page-turning story BEFORE you start?

That's what King and his pansting ilk get wrong. Muddling your way through the plot as you go is like driving without a map, in the dark, without high beams. You MIGHT get somewhere cool, awesome, new, satisfying. King often does.

But you might also end up in a ditch.

The choice is yours...

-

Is there a more classic story than man vs. nature?

Is there a more classic story than man vs. nature?

I think we all know how much fun a good survival story can be. It awakens our most basic instincts as human beings, as animals. Watching a character fight for their life against the terrifying vicissitudes of an inhospitable wilderness will get anyone's empathy-neurons firing.

But only if done well.

I don't know about you, but I've plodded through enough snooze-fest survivalist yarns to be suspicious of the genre. One can't just plant a dude in the wild and watch him survive. A writer can pour all the blood, guts, lions, and quicksand into the story that they want. They can make it fast-paced and snarky, or gritty and dark. Doesn't matter. If a story is missing these three key elements, then no reader in the world is going to care about the character fighting for their lives.

What are those three elements, you ask?

Well, let's look to one of my all-time favorite survivalist stories to find out!

In my not-so-humble opinion, The Martian is one of the best science fiction books (and movies!) in recent memory. It's eminently entertaining, and therefore worthy of study for us entertainers. Now, I'll be honest with you: it's not the best writing in the world. The prose itself is pretty pedestrian. It's not poetic, intellectual, or particularly deep in its commentary of mankind. After all, I think we'd all do our best to survive if we were stuck on Mars.

But I (and millions of other people) picked up that book and didn't put it down until we were done.

Why?

First of all, one has to consider the hook. A hook is, as you probably know by now, the thing that actually makes readers take a chance on your novel. It's the core of your story, the boiled-down concept in it's purest form, the cool thing that makes someone sit up and say 'tell me more.' Well boy does The Martian have a doozy of a hook! One could sum up this whole novel in four words: Cast Away on Mars. Boom! Right away, you know what the book is about. You know the promise the book is making to you. When picking up this story, you can expect a likable character in a desperate situation struggling to survive and return home. You'll experience the (understandable!) psychological toll and struggle of isolation in a totally foreign, interplanetary environment. On top of that, it's a contemporary, timely topic that every good sci-fi nerd has on their mind (thank you Mr. Musk). So, right out of the gate, Andy Weir is raking in the fans.

Most people would think that the second thing would be the setting, or perhaps the scientific accuracy. And don't get me wrong, those are both great! I know a lot of people who recommend this book because it uses actual science, actual research, and actual inventions based on the technology we have now. All very cool. However, that's not what kept me reading.

The second most important reason The Martian is such a success is its namesake character: Mark Watney.

Like I said, it's tempting to just plop some guy into a desperate, life-threatening situation. But that's not enough to make someone actually care. The reason you care about Watney is because he's a terrifically sympathetic main character. He's lighthearted, clever, and fun to spend time with, not to mention a bada** scientist. Within a few pages, you're charmed by his voice and rooting for him to survive. As the story progresses, you learn through the rest of the crew that he really is a great, brilliant guy, one they're all invested in saving. But even from that first page, I wanted more of Watney, was impressed by Watney, and understood Watney on a personal level. Therefore it became ever more important that he not die.

Presto! Instant page-turner.

Finally, the thing that really seals the deal for The Martian is the plot. This book takes no time at all to get moving. On the very first page, Watney is already in the most dangerous situation of his life, arguably of any human life ever. He's alone on Mars, abandoned by his crew in the midst of a dangerous storm. There's no slow build-up or info-dumping to set the stage. There's no tedious ramping up of conflict. No, the inciting incident happens before the book even starts, and the tension doesn't ever stop. Just when you think he has things figured out, something blows up, or fails. Critical life-support systems aren't trustworthy, and you read the whole book on the edge of your seat, wondering when the next shoe's going to drop. That's the mark of a good storyteller: unpredictability. The plot isn't linear, it isn't easy, and that makes it a darn fun ride.

Overall, The Martian is one of those wonderful breakout novels where the stars perfectly aligned. It was a great concept at the right time, written with a terrific voice and solid tension. The window-dressing elements of the technology and side-characters do help push the book into the stratosphere it reached (and the incredible casting of the movie pushed it further), but really The Martian is, at its core, just a really excellent example of a survival story.

Now don't mind me as I hoard oxygen canisters in my basement...

Till next time!

I confess, I'm not much one for romance novels. My few early introductions into the genre were bodice rippers featuring Fabio's bulging pectoral muscles and a woman swooning beneath a bold-face title. Needless to say, I ended up squarely in the science fiction and fantasy genre, where at the very least the covers were more discrete.

I confess, I'm not much one for romance novels. My few early introductions into the genre were bodice rippers featuring Fabio's bulging pectoral muscles and a woman swooning beneath a bold-face title. Needless to say, I ended up squarely in the science fiction and fantasy genre, where at the very least the covers were more discrete.

If you can write an excellent heist story, I can all but guarantee that fame and fortune will come knocking on your door. Everyone, and I mean everyone loves a well-constructed caper. Oceans 11, The Italian Job, The Thomas Crown Affair, The Lies of Locke Lamora, Mistborn, etc. The list goes on and on. As consumers of fiction, we love the feeling of the story shifting beneath our feet, of being outsmarted but reveling in the fact that we could have figured it out if we'd only been clever enough. Everyone knows the joy of a good twist, or a great mystery, and heist novels are chock full of both.

If you can write an excellent heist story, I can all but guarantee that fame and fortune will come knocking on your door. Everyone, and I mean everyone loves a well-constructed caper. Oceans 11, The Italian Job, The Thomas Crown Affair, The Lies of Locke Lamora, Mistborn, etc. The list goes on and on. As consumers of fiction, we love the feeling of the story shifting beneath our feet, of being outsmarted but reveling in the fact that we could have figured it out if we'd only been clever enough. Everyone knows the joy of a good twist, or a great mystery, and heist novels are chock full of both.

Is there a more classic story than man vs. nature?

Is there a more classic story than man vs. nature?

Red Rising: A Study in Trilogy Arcs

in Audrey's Archive - Reviews for Aspiring Authors

Posted

If you're a fantasy or science fiction fan, then few things are more classic than the trilogy arc. Dating back to Lord of the Rings (probably even long before that), there's something about the three-book structure that calls to the human subconscious. We like stories that break into three parts, that travel from humble beginnings to epic middle to explosive end, especially in genre fiction.

And I've seen few modern trilogies as successful at this arc than Pierce Brown's Red Rising series.

[SPOILERS AHEAD]

Red Rising starts, as many books do, with the origins of its hero. In a high-tech future where humanity has colonized the solar system and stratified into a color-coded hierarchical society, Darrow is at the very bottom as a Red. Condemned to a hard life of mining in the tunnels of Mars, he's accepted his lot in life. However, his story kicks off when his youthful wife is executed for dissent and he's recruited to serve in a rebellion called the Sons of Ares. He's transformed into a Gold, the top tier of this society, and sent to infiltrate their ranks to take them down from within.

Right away, you can see that Darrow's story is sympathetic and epic, rising up against a broken society with a righteous cause. The stakes are huge (the settled worlds, the freedom of his people) and his mission daunting. But the propulsion of his personal tragedy combined with a strong main character ropes the reader into rooting for him, despite the impossibility of his task.

In the first book, Darrow enters a school for Gold children who must fight to prove themselves, brutally if necessary. Darrow, being both genetically enhanced and also toughened by his time as a Red, manages to succeed well enough to graduate with a leadership position in book two. Even though he lacks title and history, Darrow fights hard and earns himself a strong position in Gold society, which allows him to, in Golden Son, start a war between families that begins the process of breaking down their power. Things are going well for him and he's achieving what he set out to do...

But--and this is where Brown makes his trilogy stand out--Book 2 ends with Darrow being betrayed, revealed, and knocked out of Gold society, forced to lead a truly desperate rebellion on the fringes. Morning Star is a tale of extreme risk and death-defying (or not-so-defying) stunts. It has ridiculous space battles and wild twists and every fresh reveal makes the reader question if a happy ending is even possible. Of course, the series ends with an explosive and expertly plotted climax that brings all the elements together into a satisfying finale (if you'd like more detail, then I highly recommend reading the books!).

The Red Rising series has many flaws, and each book itself has high and low points in terms of writing. But I've always looked at it as an excellent example of a trilogy, because it has such a spot-on story parabola. It begins in a low place, where its hero must fight hard and take great risks to earn himself victory. His trajectory goes up, up, up with held-breath tension and white-knuckle jeopardy. And then, perfectly timed at the end of Book 2, there's a crash. Darrow loses it all, falls to almost as low as he began, and then must start over stronger and smarter and build up victory in the right way, without the weaknesses that took him down the first time. It's a classic hero's journey, and doesn't pull any punches for the protagonist. The victory at the end feels thrilling and hard-earned because Darrow went through hell to get it, and the reader understood the stakes from the first moment in the story. The Romans-in-space setting is (you guessed it!) window dressing to an otherwise classic and archetypal structure. It's fancy toppings on your favorite flavor of ice cream, a fun new thing with a core so familiar that it's almost universal.

Which is (almost always) the foundation of high-concept ideas!

Are you writing a trilogy? If so, I highly recommend checking this one out. It's great to study, and you'll have a ton of fun while you do!