-

Posts

4,534 -

Joined

-

Last visited

Posts posted by Admin_99

-

-

There is no stronger bond in this world than family, and a caring, loving parent will do just about anything to keep his or her loved ones safe. Dive into a lake to save a drowning child, or step in front of a train to rescue a toddler who’s fallen onto the tracks. Go up against a gang of human traffickers, escape from an abusive spouse, track down a band of ruthless kidnappers.

As a mystery and thriller writer I’ve always been drawn to stories in which an innocent person encounters some sort of evil entity or force that causes him or her to risk life and limb in order to rescue a daughter or son, husband or wife. In my new novel Beyond All Doubt, a grieving widower/single stumbles onto a secret that exposes a dark secret about the recent death of his wife and places him and his young daughter in the middle of a deadly criminal enterprise. While I’d like to believe the story emerged as whole cloth from my creative mind, I’d be foolish not to admit that countless family-oriented suspense novels and movies dripped elements of suspense, tension, plot, and character onto each printed page.

With that in mind, here are 12 thriller films—some better, some worse—that undoubtedly contributed to my love of this sub-sub-genre, and which I will never tire of watching.

Taken (2008): I will look for you, I will find you and I will kill you. Every fan of the thriller genre knows this line by heart, appropriately snarled by Liam Neeson to uber-bad Albanian gangster Marko Hoxha [Arben Bajraktaraj] in the 2008 film Taken. The set-up: Devoted dad Bryan Mills [Neeson] is frantically searching for his daughter, Kim [Maggie Grace], and her friend after they’ve been abducted by sex traffickers shortly after arriving in Paris. He has just 96 hours to find them before she’s scheduled to be sold at auction, and the former government operative needs to reach deep into his bag of black ops tricks in order to come to the rescue.

Frantic (1988): While on a business trip attending a medical conference in Paris, Dr. Richard Walker [Harrison Ford] becomes understandably frantic when his wife, Sondra [Betty Buckley], is abducted from their hotel room after picking up the wrong suitcase at the airport. Limited by his thin knowledge of French language and culture, he stumbles through his interactions with the Parisian police and eventually encounters a streetwise drug smuggler named Michelle [Emmanuelle Seigner], who accidentally selected Sondra’s bag from the luggage conveyor. Self-exiled director Roman Polanski brings an intriguing mix of noire, mystery, darkness, and even a touch of comedy, causing viewers to [almost] forgive some of the glaring plot holes.

Panic Room (2002): Newly divorced mom Meg Altman [Jodie Foster] and her young daughter Sarah [Kristen Stewart] are forced to lock themselves in a concrete-and-steel panic room when three thieves break into their New York brownstone. Unbeknownst to mother and child, a fortune in bearer bonds is stashed under the floor of the impenetrable vault. [Note: these financial instruments make for a great plot device, but have been outlawed in the U.S. since the 1980s.] Foster is at the top of her game in this well-crafted women-in-jeopardy picture directed by David Fincher, whose focus on a deliberate single-setting premise delivers results in a gripping tale that builds tension one frame at a time.

Enough (2002): Based on the 1998 bestselling novel Black and Blue by Anna Quindlen, Enough stars Jennifer Lopez as Slim, an abused wife who decides to go on the run in an attempt to elude her increasing obsessive husband, Mitch [Billy Campbell], and his murderous henchmen. Desperate to get away she goes into hiding with her daughter, eventually taking self-defense classes in order to eventually exact bloody revenge. Initially panned by critics, the #MeToo movement helped to revive the movie as a statement that abused women—and their abused children—have had enough.

Last Seen Alive (2022): The plot of this film—originally known as Chase—is simple enough: When a man’s wife suddenly disappears at a gas station, his desperate search to locate her propels him down a sinister path and ultimately forces him to run from authorities and take the law into his own hands. Directed by Brian Goodman and written by Marc Frydman, it stars Gerard Butler as real estate agent Will Spann, who stops to fill up while his estranged wife Lisa [Jaimie Alexander] vanishes after she heads inside to purchase a bottle of water. It’s a good, if predictable, premise, but the story is hamstrung by trying to be both a psychological thriller and an action flick. Critics initially gave it mixed reviews but fans loved it, and when it was released on Netflix in late 2022 it instantly became the most-streamed film in the U.S.

Kidnap (2017): This film is like one of those energy shots you buy at the grocery store. At just 81 minutes long, the adrenaline surges within seconds as every parent’s worst nightmare comes true. Single working mom Karla Dyson [Halle Berry] brings her young son Frankie [Sage Correa] to a local carnival, but loses sight of him while speaking with her divorce attorney. When she spots him being dragged into a green Mustang she gives chase, first on foot and then in her own car. In a heart-thumping race against the clock, Karla pushes herself to the limit to save her son’s life.

Retribution (2023): Matt Turner [Liam Neeson again] is a man with a problem. Several, in fact. He’s in over his head at work, his kids seem to loathe him, and while he’s driving them to school one morning in Berlin, he learns from a mysterious caller that a bomb in his car will explode if they get out of the car. What typically would be a normal [albeit angst-filled] commute turns into a nerve shredding race of life vs. death, as Turner et al are sent all over the city in a twisted thrill ride of retribution while he tries to keep his kids alive.

Sleepless (2017): Set not in Seattle but Las Vegas, police officers Vincent Downs [Jamie Foxx] and his partner rob a shipment of cocaine belonging to a drug kingpin, who intended to sell it to the son of a powerful mob boss. The two cops volunteer to investigate the robbery in order to cover up their involvement, pitting them in a battle against internal affairs investigators and homicidal gangsters. Making matters worse, the gangsters kidnap Downs’ son, placing Downs in a frantic race against time to save him and bring the criminals to justice. Based on the 2011 French picture Sleepless Nights, the film is 95 minutes of kick-ass entertainment.

Peppermint (2018) The last thing Riley North [Jennifer Garner] remembers when she awakens from a coma is the brutal attack that wounded her and killed her husband and daughter. Bucking a system that’s shielding the killers from the law, the young widow transitions from an ordinary citizen to urban guerrilla. Patient and determined, she sharpens her mind, tones her spirit, and strengthens her body in order to take down those who robbed her of everything she loved. The film is both exceptionally violent and exceptionally dynamic, with little-to-none gratuitous blood or guts.

Double Jeopardy (1999): In this female-powered ‘90s action film, Libby Parsons (Ashley Judd) is wrongly convicted of killing her abusive husband, Nick. While enduring the long years behind bars she dreams of just two things: reuniting with her son and solving the mystery that took Nick’s life. When she learns that he actually faked his own death, she goes after him with impunity, knowing that double jeopardy clause in the U.S. Constitution prohibits convicting someone for the same crime twice. That questionable legal argument aside, conflict arises in the person of Travis Lehman (Tommy Lee Jones), Libby’s parole officer who dogs her frame-by-frame as she pursues Nick and tracks down her son.

Nobody (2021): What happens when a nobody becomes a somebody? That’s the story of Hutch Mansel [Bob Odenkirk], an underestimated and overlooked family man who’s mostly ignored by his emotionally estranged wife Becca [Connie Nielsen] and two children. One night, when two thieves break into the house with a gun and steal his daughter’s favorite bracelet, his long-dormant temper is triggered, propelling him down a path of dark secrets, brutal skills, and explosive revenge. Suffused with the same DNA as John Wick [screenwriter Derek Kolstad penned both], Hutch takes it upon himself to save his family from a dangerous criminal organization—and make sure no one will ever again view him as a nobody.

The Call (2013): A veteran operator for an emergency 9-1-1 dispatch center, Jordan [Halle Berry] blames herself for failing to protect a young girl during a home invasion. Six months later she fields a call from a kidnapped teen [Abigail Breslin], and forces herself to take charge of the situation and help save her life. While lacking the blood-is-thicker-than-water premise, this film is both intelligent and gripping, with only a few moments—mostly toward the end—when the storyline begins to fray. Still, it’s an intense and nerve-shredding tale of quick thinking, improvisation, and the drive to never give up.

***

-

As a society we are not just interested in jewelry heists: you might even say we are obsessed with them. Books, films, TV shows abound decade after decade from Robin Hood to Lupin. From the Moonstone to the Oceans franchise. We love jewelry robberies the point that we seem to even admire the professional criminals who carry out these robberies. Think Cary Grant in To Catch a Thief. Yes, we’re relieved to know he’s given up his thievery, but would we really be that upset if we’d discovered every once in a while, he still pocketed a diamond bauble or two.

As a writer who has been telling stories that revolve around jewelry for over a decade, I’ve often wondered at the meanings behind this fascination. Is it that we are impressed with the thieves who manage to carry out these jobs almost always without harm to anyone? Is it the vicarious thrill? Is it that we covet the gems ourselves? Or is that that, as Carl Jung suspected, many of us have a shadow self with a perpetually present “inner thief”. He said that like diamonds, we are multi-faceted—with many of our facets in our unconscious.

Gems are objects of desire for so many of us not just for their beauty and mystery, not just for their value, but because of the stories connected to them. Each gem was created hundreds of thousands if not millions of years ago. They contain all of time. They were excavated, cut, and polished, designed and set by human hands; then each one was bought, given to, and then worn by someone with a story to tell.

History certainly proves that we have always been obsessed with precious gems. Romans believed diamonds were splinters of falling stars. Ancient Greeks thought they were tears of the gods.

Over the years I’ve kept a journal of stolen gems, lost gems and jewelry robberies that have held particular fascination for me. One lost Romanov treasure inspired my 2022 historical novel The Last Tiara. And a robbery of an opal and diamond Lover’s Eye brooch from a private collection, inspired my March 2024 novel, Forgetting to Remember which is a time travel tale of romantic suspense.

If you’re as fascinated as I am by stolen gems, here are some of the most outrageous, successful, and simply stunning thefts of the last hundred years.

The Great Pearl Robbery of 1913. The “Mona Lisa of Pearls” a necklace of 61 flawless pink pearls was sent from Paris to a London. But upon receipt, jeweler Max Mayer found the pearls were missing and instead he’d been sent lumps of sugar. The thief, Joseph Grizzard, was eventually captured and the pearls found—by chance—when a piano-maker walking on the street saw a man drop something and then suspiciously hurry way. Examining the refuse, the piano play found a broken string of pearls. He took them to the police and received a large reward.

The InterContinental Carlton, Cannes. One of the most famous hotels on the on the French Riviera, the Carlton was featured Alfred Hitchcock’s, To Catch a Thief. The hotel’s first robbery occurred in 1944. Thieves burst into the hotel’s jewelry store firing machine guns walked out with gems worth between $43 and $77 million. In 2013, the hotel hosted an “Extraordinary Diamonds” exhibit. A single gunman, in less than a minute, walked away with $136 million in precious stones. He escaped through a window.

Antwerp Diamond Centre, Belgium. Often called “the heist of the century.” In 2003 over $100 million worth of diamonds, gold, silver was taken. The thief Notarbartolo was arrested for heading a ring of Italian thieves known as the School of Turin, but the items were never found.

Harry Winston, Paris. In 2008 a group of thieves, some disguised as women, robbed the famous house of Winston of $102 million. They addressed the employees by name, showed off a hand grenade and a gun. A car waited for them, and they made a clean escape. But only for a time. The eight men were eventually caught and convicted, one of them having once been a security guard at the store.

American Museum of Natural History, New York. Being a New Yorker, this has always been one of my favorites. In 1964, two men scaled a fence and snuck into the J.P. Morgan Hall of Gems and Minerals where they gathered up their loot. In all they took 24 gems, including the Star of India (the world’s biggest sapphire, weighing 563.35 carats); the DeLong Star Ruby (100.32 carats, and considered the world’s most perfect), and the Midnight Star (the largest black sapphire, at 116 carats). They got away in regular yellow cabs with $410,000 worth of gems, which today would be worth more than $3 million. After a long investigation nine of the gems were discovered in a locker at a bus terminal in Florida. 14 of the gems are still missing.

The Damiani Showroom, Milan. Thieves dressed in police uniforms arrived at the not yet open showroom asking the staff for store records. Using electrical cables they tied the staff up, sealing their mouths shut with tape, and then locked them in a bathroom. Millions of dollars were stolen during the robbery which took 40 minutes. Luckily, some of the firm’s most valuable jewels were not in the showroom as they were being lent out to celebrities for award shows in Los Angeles.

***

-

Over the past few years, there’s been quite a few novels popping up featuring translators solving crimes. Some of the books are by authors who themselves have experience in translation, and reward readers with their turns of phrase and tricks of prose lifted from the cadences of other languages. I try to keep abreast of trends in the genre, especially ones difficult to google (if you search for crime fiction about translators, you’re likely to find works of fiction in translation instead), and I’ve found the mother-lode with this one (or perhaps, the mother tongue?).

In particular, I put together this list because two books this year demanded it: Jennifer Croft, the award-winning translator of Olga Togarczuk, published her first novel in March, and one of April’s standout releases is The Translator, by Harriet Crawley, a novel of the “new Cold War” by a writer with decades of experience in Russia under her belt with the linguistic skills to match. While authenticity is not always a reasonable demand in our genre (we wouldn’t want actual murderers writing crime fiction), the authors below all appear to be nearly as multi-lingual as their characters.

Jennifer Croft, The Extinction of Irena Ray

(Bloomsbury)Jennifer Croft is the renowned translator of Olga Tokarczuk and this debut takes full advantage of her background in the best way possible. In this complex and metaphysical mystery, eight translators arrive at a sprawling home in the Polish forest, only to find their author has gone missing. Where is Irena Ray? What secrets has she been keeping from her devoted fans? And what’s with all the slime mold? I should add that this title is quickly becoming a favorite of all of us here at CrimeReads!

Harriet Crawley, The Translator

(Bitter Lemon)Harriet Crawley was married to a Russian, lived and worked in Russia for decades, and is a fluent Russian speaker, so it’s no surprise that her 2017-set novel feels as authentic as a le Carre tale when it comes to underhanded deeds and doomed romance. Crawley’s narrator is a skilled translator called up by the British government to help negotiate an important trade deal. His mission soon goes off-course when he encounters another translator, his former lover, who needs his help: her surrogate son, a hacker who got on the wrong side of the FSB, has died suspiciously, with few interested in a thorough investigation.

Eddie Robson, Drunk on All Your Strange New Words

(Tordotcom)This book is so strange! In the distant scifi future, the bumbling interpreter to an erudite alien attaché must solve a locked-room mystery or find her employment jeopardized. The act of translating the alien tongue makes her feel a bit tipsy, but that’s just the start of her problems in this wildly creative scifi/mystery mashup.

Ann Leckie, Translation State

(Orbit)Ann Leckie’s Translation State is part space opera, part murder mystery, and all entertaining. The set-up is compelling: two seekers converge in their quest to solve the mysterious disappearance of a skilled, but rebellious, translator, the key to avoiding a clash between titans as their political overlords prepare to renegotiate a controversial arrangement.

R. F. Kuang, Babel, Or, An Arcane History of the Oxford Translators’ Rebellion

(Harper Voyager)One of my go-to recommendations at parties! In R. F. Kuang’s anti-colonialist powerhouse, magic comes from the meaning lost or gained in a word’s translation, and the more used the language, the less power it provides. In the early 19th century, the Oxford Dons have recruited speakers of many tongues from across the empire to keep magic plentiful, gathering them from the periphery to the center. While these students are initially enamored of academia, they eventually begin a costly rebellion against those who would exploit their talents and their people. I know, it’s not crime fiction, but it does contain some subterfuge.

Ayesha Manazir Siddiqi, The Centre

(Zando)I can’t give away too much about this bizarre take on how the rich get ahead, but it’s got a killer twist! In The Centre, a woman learns of an exclusive language school promising near-instantaneous fluency in a variety of difficult tongues. She heads to the facility’s remote, spa-like location and bonds quickly with the woman in charge of the complex operation while throwing herself wholeheartedly into the center’s immersive process. Her commitments will be tested, however, when she finally understands the true cost behind the school’s innovations.

-

What makes an academic institution the perfect setting for fictional crime? Perhaps it’s because there is so much at stake when a child or young adult is exposed to a crime. A campus, whether primary, secondary or tertiary, offers the potential for a juicy closed-room thriller – not to mention a substantial roll of suspects from a pool of pupils, teachers and parents.

When I wrote my third novel The School Run, I chose a fictional private high school for my sinister goings-on. St Ignatius Boys’ Grammar was an institution so hallowed and revered that mothers would do anything to get an admissions offer for their sons – including commit murder. It was so intriguing to me, the idea of this wealthy battlefield: a prestigious, academic and historic place, with lawns and cricket pavilions ripe for murder and corridors that were ominous and threatening after dark.

I was inspired, in part, by my son starting high school, and also the aftermath of the 2019 college admissions scandal – the now infamous criminal conspiracy by celebrities and college officials to influence undergraduate admissions. It made me think: if a mother will commit this kind of a crime for her child, what else would she do? How far would she go?

I’m a huge fan of campus novels purely for the intrigue and the fruitful platter of suspects. When I was making this list there were so many gritty stories that sprang to mind. Here are six of my favourites.

The Secret History, by Donna Tartt

This has to be the ultimate in campus crime novels, and it is certainly my favourite. Richard is recounting his years at an elite university in Vermont, and straight away we learn he and a group of fellow students – under the influence of their cult-like Ancient Greek professor – killed an unlikeable student named Bunny. I read this novel in a tent in Kenya on safari several years ago and the eeriness was real as I flipped the pages. It is not so much an action-packed whodunnit but an intellectual thriller that will give you the chills as much for its creepiness as its outstanding cleverness.

What Was She Thinking? (Notes on a Scandal), by Zoe Heller

Barbara Covett is a lonely and introverted school teacher who attaches herself to the new art teacher at St George’s School in north London, the whimsical and childlike Sheba Hart. When Sheba begins an illicit affair with a fifteen-year-old male pupil, Barbara uses the situation to her own advantage, claiming a sort of ‘ownership’ over Sheba. The crime in this story (nominated for the 2003 Man Booker Prize and later made in to a film starring Cate Blanchett and Dame Judi Dench) is obviously Sheba’s sexual relationship with a minor, which makes for uncomfortable reading. But so does Barbara. A gritty psychological thriller that touches on obsession, victimhood and regret.

Anatomy of a Scandal, by Sarah Vaughan

Politicians who believe themselves above the law, a drunken night at Oxford University that sees a man killed and a woman left deeply traumatised, and a court case with an almighty twist. This story, which was recently adapted for Netflix, is told in current day London, and also via flashbacks to our protagonists are at Oxford University swilling booze and behaving badly. One night it all goes horribly wrong and a woman’s life is destroyed forever due to an horrific sexual assault, and so she seeks her lawful revenge in the present day.

Oxford holds its own as a character in this novel, the university as debauched and unscrupulous as its campus inhabitants.

The Scholar, by Dervla McTiernan

Irish-Australian author McTiernan is well known for her gritty crime novels, and this, her second, is set at Ireland’s Galway University. It centres around the hit and run of a young woman who is the daughter of the head of a pharmaceutical giant, Darcy Therapeutics. The company’s influence is vast, from government to philanthropy, and so when the evidence begins to point towards a Darcy laboratory, the stakes for those involved become terrifyingly high. The second in McTiernan’s Detective Cormac Reilly series, this novel is propulsive, twisty and perfect for those who love a tense police procedural.

Who We Were, by B.M. Carroll

The tagline for this story is: ‘It’s been twenty years, but all is not forgiven.’ A tantalising story split between the current day with a school reunion in the planning, and back at Macquarie High when there was an adored (and hated) queen bee, a cruel bully and a hapless victim. Friends and enemies are brought back together as adults, reunited for the first time in two decades, and they bring with them the grudges they have each held on to since their teens. Not a knife-wielding, hold-your-breath-for-the-murder crime novel, but rather a clever campus noir with a good deal of focus on character and motive. Liane Moriarty called it ‘addictive’ for a reason.

Cat Among the Pigeons, by Agatha Christie

Agatha Christie fed and watered my love of crime stories as a teenager. This novel, first published in 1959, is set at exclusive girls’ school called Meadowbank where the body of the games mistress at is found in the sports pavilion among the lacrosse sticks. She has been shot through the heart, and now there is a cat among the pigeons. Enter Christie’s most famous character, Belgian detective Hercule Poirot, to investigate. The story is typical Christie with a somehow more light-hearted tone, although as one reviewer puts it ‘there is a shocking lack of cats and pigeons in this book’.

***

-

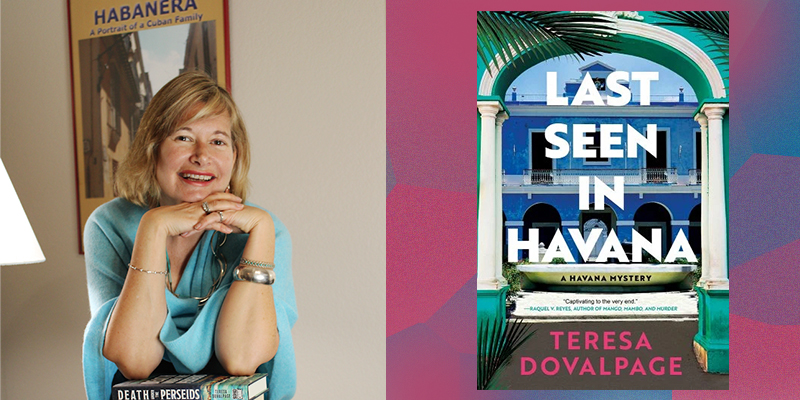

Last Seen in Havana, a suspenseful addition to Teresa Dovalpage’s Havana Mystery series, was released by Soho Press in February 2024. The novel, which takes place in Havana poignantly captures the perspectives and experiences of Sarah Lee Nelson, a young woman from San Diego who remains in Cuba in 1986, after falling in love with a Cuban man, and Mercedes Spivey, a Cuban-born professional baker, who returns to Havana from the U.S. in 2019 to help the ailing grandmother who raised her. In alternating chapters, Last Seen in Havana leaps from the mid-1980s to a time that just precedes the pandemic in unspooling a powerfully moving mystery, one that will stay with readers long after the last page has been turned.

I have had the great good fortune of knowing Teresa Dovalpage for more than twenty years, as a friend and a fan of her books. I’m thrilled to have the chance to discuss with her this latest addition to her estimable oeuvre.

Lorraine Lopez: In Last Seen in Havana, you present dual narratives from two main characters, capturing the first-person perspective of Mercedes and the third-person limited POV of Sarah. How did you manage to braid both strands so well, transitioning from one character to the other in such a clear and seamless way? And what were some of the challenges you faced in telling the story this way?

Teresa Dovalpage: This was the first time I’ve tried a dual narrative so I am happy to know it reads fine. The idea of a novel about Mercedes’ search for her mother was in the back of my mind since I wrote Death under the Perseids. But I realized I needed more of a background story for it to be compelling. If readers didn’t know much about Mercedes’ mother, Sarah, why would they care about her? The biggest challenge was writing Sarah’s chapters. At first, they were letters she wrote to her friend Rob, but they sounded a bit off—I couldn’t get a young, surf-loving San Diegan’s voice right. So, I shifted to the third-person limited narrator and it worked much better.

LL: John Gardner calls compelling concrete details “proofs.” In presenting two time periods, you provide convincing temporal and place “proofs.” By what means—research, experience, memory—did you mine information for such significant detail?

TD: Getting the “proofs” was a walk down memory lane. I lived for my first thirty years in Cuba so it wasn’t hard to remember the details: the May First celebrations, the Russian presence (of course, in the 80s we called Russians “our Soviet comrades”), the diplotiendas (dollar stores), all that… But I also asked my mother and friends about the “good old bad old times,” and watched Cuban documentaries from those years, so I felt I was living in the 80s while writing the book. It was fun to go back in time in search of the “proofs!”

LL: In an essay in An Angle of Vision, wherein you describe cleaning an old and decrepit refrigerator, you mention determination to be apolitical in your writing. I believe you achieve this quite well, especially in this novel, where you observe circumstances without passing judgment on political contexts, allowing readers to draw their own conclusions. Why is this important to you as an author?

TD: I remember An Angle of Vision! So does my mother, who loves to remind me that I seldom cleaned the cabrón refrigerador. Anyway, growing up in Cuba, I had to read too many socialist realism novels. Thankfully, most of them are forgotten now! The sad part is that not all the authors were bad writers—I actually liked Manuel Cofiño’s work, without the politics. But the fact that politics were shoved down the readers’ throats made me hate its inclusion in my own work. Too much blablablá, political or otherwise, and readers will close the book and start playing with their phones.

LL: Friendship between women factors into the novel in an important way. Mercedes travels to Cuba supported by her friend Candela who accompanies her. Sarah forges connections with Dolores and Valentina, who offer her practical help and guidance. What is your view of these relationships? Do they enable the protagonists or provide genuine resources?

TD: I don’t know what I would do without my amigas! You are one of them! Friends provide so much needed support in life and literature…The reason why female friendships appear so often in my books is because they are part of my own experience. As a narrative resource, Candela gave me a chance to present Cuba as seen through American eyes—the questions she asks Mercedes are those that my American friends have about Cuba. The connections that Sarah forges with Dolores and Valentina are a way to showcase two ways of looking at the Cuban reality of the 80s: a Russian woman married to a Cuban man (which was quite common then), aware of the changes happening in Eastern Europe in the late 80s, and a committed Cuban revolutionary who has no idea of what was going on in the world at that time.

LL: In terms of characterization, Villa Santa Marta, the house where Mamina lives and where Mercedes grew up, emerges as an antagonist, one that poses physical threat to its occupants. At one point, Mercedes observes, “[T]he fact is, we lived in an angry house.” What was your idea behind casting Villa Santa Marta as a villain the novel?

TD: Places are fun characters to write about, more so when they are bad or scary, like Villa Santa Marta. I used to visit a house in Miramar, which I used as a model for the story, that had such a bad vibe that it gave me the creeps every time I went there. The fact that two people were killed in that house (in real life) reinforced the impression. I knew I would use it in a story someday.

LL: As an avid fan of the Havana Mystery Series, I’m eager to know what lies ahead for you. Can we expect another novel in the series? What are you working on now?

TD: In the book I am working now, Teresita is a woman in her fifties who lives in the US and writes mystery novels. Her journey as a writer started with an unsolved case she witnessed as a teenager: a teacher and a student who died in a suspected murder-suicide case at the middle school she attended. When her best friend is accused of committing that forty-year-old crime, Teresita goes back to Havana in an attempt to figure out what really happened on that April 1980 day. I loved turning myself into a character!

***

-

Cozy mysteries are having a moment. The sub-genre is expanding and has resulted in a surge of popularity. Modern cozies maintain the core elements including a light-hearted tone, an amateur sleuth, and no graphic sex or violence. Yet they’ve become more inclusive and expanded their boundaries to embrace current technology as well as the use of contemporary verbiage. The shift has infused a new energy into the category, bringing with it themes and humor that resonate with a broader readership.

When writing my new cozy, Peril in Pink, I was inspired by the modern mysteries I’d been reading. Without a doubt, I knew I wanted my book to be in that lane, too, particularly when it came to the humor. The relatable quips and fun banter between characters felt fresh.

Here is a list of some of the modern cozies coming out in 2024 to keep on your radar.

The first in the heart-warming and deliciously mysterious Magical Fortune Cookie series from Lefty Award-nominee Jennifer J. Chow.

Readers are introduced to Felicity Jin and her family’s magical bakery in the quaint town of Pixie, California. Her mother’s enchanted baked goods bring instant joy to anyone who eats them.

After some failed attempts, Felicity creates a fortune cookie recipe that becomes a huge hit. Things are going well until one of her customers is murdered. The personalized prediction draws suspicion from the police and she becomes a prime suspect. Felicity has no choice but to get involved. She must clear her name and turn her luck around.

The second book in the Hayden & Friends Mystery series, readers are treated to some daring excitement!

Dating blogger Hayden McCall and his best friend Hollister are once again drawn into a murder mystery after attending an upscale circus arts show. It’s a fundraiser featuring magic, acrobatics, and a Michelin-star dinner.

Things start to go wrong when the celebrity performer is a no-show. Then Hayden’s frenemy, Sarah Lee, finds the missing star dead in her hotel suite. Sarah Lee turns to Hayden for help. With a cast that includes a trapeze artist, a cowgirl comedian sharp-shooter, and a sexy troop of Romanian male acrobats, there’s no shortage of suspects to choose from. Hayden and Hollister need to act fast before Sarah Lee is charged with murder and the real killer performs a disappearing act.

The rhythm is gonna get you.

What a fun tag line! Rhythm and Clues is the third book in the Record Shop Mystery series. It features Juni Jessup and her two sisters, Tansy and Maggie. Together they own Sip & Spin Records.The sisters are under pressure from predatory investors and the struggling vinyl record/coffee shop is in trouble. Things go from bad to worse when a sketchy financier is found dead outside their shop during a thunderstorm.

Then the nearby river spits out an unexpected surprise and Detective Beau Russell, Juni’s ex, asks for her help. With washed out roads and the whole town on alert, Juni must hurry before someone else gets hurt.

Influencer Maddy Montgomery is at it again in A Cup of Flour, A Pinch of Death…

Maddy Montgomery has turned Baby Cakes Bakery into a huge success after inheriting it from her great aunt Octavia. But not all the attention she’s drawn to the bakery is good. Her former nemesis, Brandy Denton, shows up and disrupts a vlog Maddy is making. Their argument snags the attention of viewers and the video goes viral. Then Brandy is found dead and Maddy becomes a murder suspect.

With the help of her aunt’s friends, the Baker Street Irregulars and her English mastiff Baby, Maddy digs into the case. She must unearth some secrets and find the truth.

Time to tune into Peter Penwell and JP Broadway’s HGTV hit reality show Domestic Partners for a Halloween themed mystery.

Peter Penwell and JP Broadway are excited to kick off season three of their hit show with a fixer-upper that’s rumored to be a haunted house. Twenty-five years ago automotive heiress and beauty queen Emma Wheeler-Woods fell from a third-floor balcony to her death at a Halloween night party inside a lavish manor home in the Detroit suburb of Pleasant Woods.

Fiona Forrest, who recently inherited the home after learning she is Emma’s daughter, hires Domestic Partners to restore the property. But ghostly sightings, deep secrets, and sabotage have Peter and JP wondering if the place is haunted and if Fiona’s mother was actually murdered.

They hustle to finish the project by Halloween—the anniversary of Emma’s death. Can they finish the work, shoot the finale, and solve a cold case before someone else ends up dead?

It’s Autumn in Shady Palms and Lila Macapagal and her Brew-ha Café crew are at it again.

It’s the annual Corn Festival, a big deal in Shady Palms. Lila is happy to participate and have some fun. She and her friends at the Brew-ha Café even put a wager on who can make it through the fastest.

Then a dead body is found in the middle of the corn maze, and Adeena Awan, one of the Brew-ha crew, is found unconscious next to the body. Even worse? She’s holding a bloody knife.

Lila knows Adeena is no killer so she gears up to find the real culprit and prove her friend is innocent.

The lazy, hazy, dairy days of summer are coming to a close in the Sonoma Valley… and so is someone’s life.

Willa Bauer is at it again! Willa, owner of the Curds and Whey Cheese Shop in Yarrow Glen, is gearing up for the annual Labor Day weekend bash: Dairy Days, in neighboring Lockwood. Willa is thrilled to celebrate her favorite things—she is a cheesemonger after all—and this festival goes all out: butter sculptures, goat races, cheese wheel relays, even a Miss Dairy pageant. Too bad the pageant runner, Nadine, is treating Dairy Days prep like it’s fondue or die and is putting everyone around her on edge.

When Willa finds Nadine’s dead body under years’ worth of ceramic milk jugs, the police are slow to want to call the death anything but an accident. But fingers are pointing at Willa’s employee, Mrs. Schultz, who stepped in to help the pageant after Nadine’s death. Someone wanted Nadine out of the whey, and Willa is going to find out who.

***

-

During the early years of the pandemic, I escaped into horror movies and books. There is something soothing about sitting at home alone in the dark, hiding from the outside world. There is a cool control to be found watching fictional evil on my computer screen, or falling asleep reading a well-worn horror paperback for a story whose ending I already knew. At the end of the day I can shut off the screen, close the book, push the horror away.

Fictional horror is often my escape from the horrors of the real world, a place to practice survival strategies and map out escape routes.As a Black woman who loves horror, fictional horror is often my escape from the horrors of the real world, a place to practice survival strategies and map out escape routes. At moments when my life has felt out of control, I’ve outlined and started half a dozen horror novels. I’ve written my fears and anxieties into the plotlines of short stories. I’ve written about Black women and girls and Black families escaping monsters because sometimes it’s so hard to escape them in our real lives.

It felt necessary to write Black people surviving and winning against insurmountable evil during years filled with so much Black death. COVID-19 steamrolled through Black communities in the last four years, making us one of the hardest hit in terms of illness and death. Police violence against Black bodies continues to splash across our social media. All this while right-wing attacks against racial progress have resulted in the end of affirmative action, the pullback from DEI, the banning of Black books, and the exclusion of Black history in schools. When so much is out to erase your very existence, fear becomes a constant part of your life.

In horror I see my fear and terror at a world beyond my control reflected back at me. For Black people, horror can provide a safe environment to process the trauma from our daily lives. Horror can offer us a powerful space to imagine fighting back and making it out. To imagine survival.

The Monstrous Other Emerges

Horror is one of the oldest storytelling genres, with its roots in our oral storytelling traditions, myths, folktales, and fairytales, all of which have always contained elements of the unknown, the grotesque, and the supernatural. Most mainstream Western horror traces its roots to the Gothic tales of the late 18th century. In these Gothic novels, ghosts, soulless monsters, and unsettling terrains filled readers with feelings of foreboding, unease, terror, and fear, the defining characteristics of the modern horror genre.

What is specific to this time period in the birth of modern horror is its connection to European colonialism. Western horror has long been obsessed with otherness, because it sits at the juncture of Western imperialism and the creation of a racialized “Monstrous Other” as an integral feature of 18th and 19th century Western speculative fiction. Much of this fiction would become a site in which white European’s fears, desires, cultural anxieties, and fantasies played out. European colonialism and racism needed to create “monsters” out of the people being colonized so that Europe could justify destroying and enslaving those populations. When one is positioned as the “Monstrous Other” by the dominant culture one is considered completely unassimilable, making it easier for these groups to be marked for destruction and death. Equating Blackness with monstrosity, and darkness with evil in the popular imagination was one of the largest enactments of racialization in Western literature.

This racialization would continue into the 20th century, which meant Black characters would be mostly non-existent, or sidelined and marginalized in horror film and literature. Often we were the monsters, or the monsters were a stand-in for Black people and other people of color. And if we did exist beyond monsterdom, Black characters fulfilled stereotypical roles or tropes, never receiving the development or depth given to white characters.

Black characters often showed up as background or side characters in three specific ways: as the token Black sidekick or best friend to the white protagonist; as the “Magical Negro” with special wisdom or powers that can be used to assist the white protagonist; and as the notorious “First to Die” or Sacrificial Negro, where the Black character either died first, or existed only to save a white character and is killed off soon after. Horror reinforced the slave-era idea that Black bodies should only exist in service to whiteness, and that Black people were worth less than the white people who got to survive to the end.

Enter Black Horror

A decade ago the Black Lives Matter movement first spread across the country, spurring massive conversations about anti-Black racism in the United States and its institutions. As a social movement it inspired a renaissance in all Black artforms, including the literary world. For years the lack of diversity in publishing translated to a lack of Black authors being published across all genres. Fortunately, the push for greater diversity in publishing has brought more Black writers to our bookshelves over the past few years, seeding a Black literary renaissance.

In the realm of SFFH, two critical cinematic moments also helped to increase visibility. The success of Jordan Peele’s 2017 Oscar-winning directorial debut Get Out did for Black horror what Black Panther did for Black science fiction a year later, amplifying interest in the often under-resourced and overlooked work Black writers have been doing in these speculative genres. In the years since, Black horror storytellers have had more freedom to talk back to the genre, inserting Black characters front and center as heroes and survivors.

Nia DaCosta’s reimagined Candyman broke pandemic-box office records in 2021. HBO’s 2020 hit series from showrunner Misha Green, Lovecraft Country, still remains a talked about series despite its contentious cancellation. Black horror anthology TV series such as Amazon Prime’s Them and Shudder’s Horror Noire, offered Black writers and directors a chance to see their stories come to life on screen.

At long last, we’re beginning to get Black horror book adaptations. In 2022 the long-awaited television adaptation of Octavia E. Butler’s genre-blending time travel classic Kindred premiered. This past year saw the adaptation of Zakiya Dalila Harris’s social horror The Other Black Girl and Victor LaValle’s dark fairy-tale The Changeling.

During this Black horror renaissance, Black actors were cast as leads in several horror movies, including Master, Nanny, His House, The Invitation, Bad Hair, Antebellum, Vampires vs. The Bronx, The Blackening, Talk to Me, and The Angry Black Girl and Her Monster. Black actors also landed lead roles in several horror TV series. Among my favorite performances include Saniyya Sidney in The Passage; Harold Perrineau in From; Dominique Fishback in Swarm; André Holland in Castle Rock; Leslie Odom Jr. in The Exorcist: Believer; and Mamoudou Athie in Archive 81. We also saw Black and interracial families leading horror shows like Netflix’ The October Faction, and in movies like Disney’s 2023 Haunted Mansion and Netflix’ We Have a Ghost.

For Generation Xers and Millenials who gorged our love of horror via 90’s pulp teen horror paperbacks, we were treated to diverse castings in recent television adaptations. We saw Black leads in Netflix’ 2022 The Midnight Club, based on the book by Christopher Pike, and Black leads in two series set in the worlds of R.L. Stine — 2021’s Fear Street Trilogy and 2023’s Goosebumps series.

We’ve seen more Black Final Girls in the past few years as well. Some of my recent favorites include Georgina Campbell’s Tess in Barbarian, Kiersey Clemons’ Jenn in Sweetheart, Taylor Russel’s Zoey in Escape Room, and Keke Palmer’s Emerald in Nope.

We’ve Always Loved Horror

Even before Peele, Black horror had a rich literary lineage going back to the folklore of Africa and its Diaspora. Stories of haints, witches, curses, and magic of all kinds can be found in the folktales collected by author and anthropologist Zora Neale Hurston and in the folktales retold by acclaimed children’s book author Virginia Hamilton. One of my earliest childhood literary memories is being entranced by Hamilton’s The House of Dies Drear and Patricia McKissack’s children’s book classic The Dark-Thirty: Southern Tales of the Supernatural, both examples of the ways Black authors have tapped into Black history along with our rich ghostlore.

I’ve taught Black Speculative Fiction at the university level, and I always include a section on Black horror. This past year I taught short stories like Eden Royce’s “The Choking Kind,” P. Djèlí Clark’s “The Secret Lives of the Nine Negro Teeth of George Washington,” Nalo Hopkinson’s “Greedy Choke Puppy,” Kai Ashante Wilson’s “The Devil in America,” and Tananarive Due’s “Free Jim’s Mine.” I try to introduce students to a range of what Black SFFH can do in the hands of Black writers writing from our own cultural folklore and specific histories, from our own traumas and realities. Our lens on the world is unique, and our horror writing speaks to that.

Even before Peele, Black horror had a rich literary lineage going back to the folklore of Africa and its Diaspora.Black horror can be clever and subversive, allowing Black writers to move against racist tropes, to reconfigure who stands at the center of a story, and to shift the focus from the dominant narrative to that which is hidden, submerged. To ask: what happens when the group that was Othered, gets to tell their side of the story?

Black horror allows us to ask questions about the unique role Blackness plays in allowing us to rethink almost every piece of speculative worldbuilding—how does the meaning of vampirism and immortality shift as it intersects with race in books such as Fledgling by Octavia E. Butler, The Gilda Stories by Jewelle Gomez, the African Immortals series by Tananarive Due, and the Vampire Huntress Legend series by the late L.A. Banks? Yes, I do love vampire fiction.

Black horror gives Black writers the chance to talk back to and critique icons in the genre like H. P. Lovecraft, something we see in P. Djèlí Clark’s Ring Shout, Victor LaValle’s The Ballad of Black Tom, and N. K. Jemisin’s The City We Became.

Black horror situates Toni Morrison’s Beloved as a classic work of Gothic horror that uses genre tropes to showcase the real-life horrors of slavery and racism. Some of the richest writing in Black horror follows this Black Gothic footprint, or what AfroSpeculative comic artist John Jennings calls an “ethnogothic” framework, where supernatural and gothic tropes are used to distill ideas around the horrors of racist oppression.

Black horror allows Black writers to claim our place as architects of the Southern Gothic as well, bringing attention to a distinctly Black Southern Gothic. No one better represents this subgenre today than two-time National Book Award winner Jesmyn Ward. Her last two novels, Sing, Unburied, Sing and Let Us Descend beautifully blend the supernatural and the real-world horrors of the rural Southern Black poor, while also showing how Black ancestral folkways and traditions can be tapped as resources for a character’s transformation and empowerment. Her work sits alongside Black women-helmed Southern Gothic classics such as Julie Dash’s Daughters of the Dust, Kasi Lemmons’ Eve’s Bayou, and Gloria Naylor’s Mama Day.

In this rich Black Southern Gothic landscape, many amazing books have emerged, including Tananarive Due’s The Reformatory, LaTanya McQueen’s When the Reckoning Comes, Johnny Compton’s The Spite House, and Monica Brashears’ House of Cotton. Outside of the Southern setting, gothic tension winds cleverly through Rivers Solomon’s Sorrowland, Alexis Henderson’s The Year of the Witching, and Elisabeth Thomas’s Catherine House. Horror-tinged thrillers like Jackal by Erin E. Adams and When No One Is Watching by Alyssa Cole have shown how real-world Black experiences can be powerful forces in building mystery and suspense.

The Black horror boom has traversed age categories as well, resulting in more Black horror in young-adult and middle-grade fiction. Justina Ireland is a predecessor in Black YA horror, and her books like Dread Nation stand out for their unique blending of historical settings with the fantastic. Black YA horror continues to span the horror subgenres, from ghostly hauntings to urban legends to zombies. Several examples include: The Taking of Jake Livingston by Ryan Douglass, The Weight Of Blood by Tiffany D. Jackson, Burn Down, Rise Up by Vincent Tirado, The Getaway by Lamar Giles, The Undead Truth of Us by Britney Lewis, The Forest Demands Its Due by Kosoko Jackson, and Delicious Monsters by Liselle Sambury.

The Final Girl is Black

The YA Black horror anthology I co-edit with Saraciea J. Fennell, The Black Girl Survives in This One, came out this month, and it finds company with recent Black Horror anthologies like Jordan Peele’s Out There Screaming, Circe Moskowitz’ All These Sunken Souls, and Terry J. Benton-Walker’s forthcoming The White Guy Dies First. It also makes itself at home next to recent books featuring Black Final Girls, such as There’s No Way I’d Die First by Lisa Springer, Their Vicious Games by Joelle Wellington, You’re Not Supposed to Die Tonight by Kalynn Bayron, and Dead Girls Walking by Sami Ellis.

In The Black Girl Survives in This One, we purposely subvert the idea of the Final Girl, which has typically been that of a virtuous white teen girl or white woman in her 20s who defeats the powerful villain and lives to tell the tale. We wanted to move Black teen girls from their conventional sidekick role of “sassy best friend” to the very center of the story. Doing so provides a healing moment for us as Black writers and Black readers. It is so vital to see narratives of Black women and girls surviving, in a world where anti-Black violence and violence against Black women and girls is still a true life horror story.

My story in the collection, The Brides of Devil’s Bayou, explores how trauma is passed down in Black families. Aja, my Final Girl, is caught in a powerful family curse. I was interested in the idea of the curses we inherit, and how the horrors of the past manifest in the present. I was also interested in the ways Black woman not only carry our own demons, but our mother’s demons, and our grandmother’s demons, without even knowing it. I wanted to use the supernatural to illustrate generational trauma made manifest.

Many of the stories in the anthology hint at the underlying terror of Black girlhood, the psychological trauma and the hyper-vigilance Black women and girls face on a daily basis, in just fighting to be heard, seen, or believed. There is a natural survival instinct underlying how Black women and girls already move through the world that gives depth to our roles as final girls. It’s powerful to see yourself survive in a world that has not always valued your life. In this way, Black final girls are revolutionary. Something poet Lucille Clifton once wrote about Black womanhood rings true here: “Come celebrate with me that everyday something has tried to kill me and has failed.”

***

-

It was early 2021 and I couldn’t stop thinking about the eighties. For you maybe it was the seventies, or early 2000s, or whatever time it was that whisked you back to your youth, what we collectively call the good ole days, even if we can never all agree on when those days were. That period of time when things were easier, life was simple, people were less divided. Most of all, a time when there wasn’t a goddamn pandemic going on. In short, in 2021 I was feeling profoundly nostalgic.

Every writer I know—including myself—was getting the same question: how are you going to write the pandemic? People wanted to know how novelists were going to set books in modern-day and if we were going to have the pandemic serve as a backdrop, or even a character.

I got these questions and had no answers, because the pandemic made me want to write about anything BUT modern day. My books are dark enough, I didn’t want reality sending my readers into a depression-spiral. Moreover, I wanted to stick my head in the sand, ignore everything around me, and write about when I was living as a teenager in the Los Angeles suburbs in the mid-to-late-1980’s. Funny thing is, a lot of my writing friends were feeling the same thing, and damn if we aren’t now seeing a slew of fiction coming out set in the past. My newly released thriller The Father She Went to Find is my pandemic book, and it all takes place in 1987 (is that long enough ago to be considered historical fiction? Probably not).

Everyone needed an escape in 2020 and 2021, and for many authors that meant writing about their version of the good ole days. But the naked truth is there’s no such thing. All days are amazing, and all days are the stuff of nightmares. Everything is perspective, and the foundations of perspective are memory and ignorance. If you have fond memories of a certain decade, it’s usually a result of how long ago that decade was and how naïve you were at the time. In the 1980’s, I was exceptionally young and stupid.

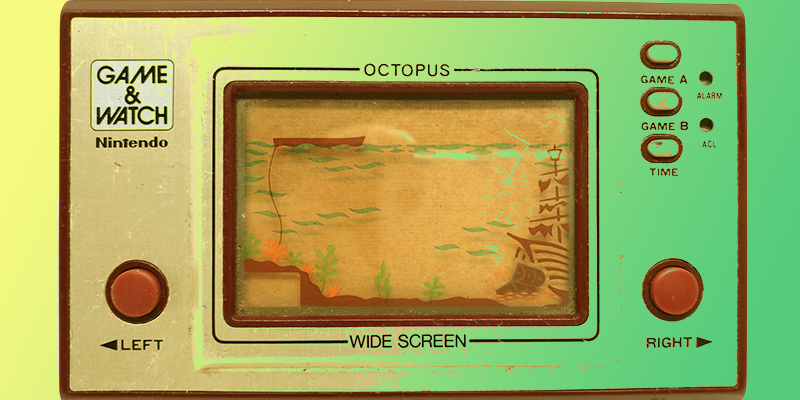

But that’s good! I write thrillers, and no matter how Pollyannaish my memories of the 80s are (mall arcades! mix tapes! whitewash jeans! Cyndi Lauper!), there are haunting things about that decade that make it a delicious time period in which to set a novel.

Cocaine was killing people even though it was more common than Guess jeans. Crack was disproportionately destroying Black families while Nancy Reagan was blithely telling folks all you had to do was say no. Massive industry deregulation allowed Wall Street bankers to do whatever the hell they wanted, and they did. Oliver North was the symbol of all the lies the government was desperately trying to hide. Smoking on airplanes was still allowed, chickenpox parties were a thing, hitting your kid was an accepted form of parenting, and if you had to murder someone to get that limited-edition Cabbage Patch Doll, well, we’ll just look the other way for a few minutes while you do it.

Oh, and nuclear war. That was going to happen at any moment. For pretty much the entire decade. At school, our nuclear-strike drills consisted of the (useless) actions of either cowering under our desks or running outside, because what school district can afford thousands of radiation suits?

We always think the current decade is the worst of all time, but all decades are sublime and terrible in their own ways.We always think the current decade is the worst of all time, but all decades are sublime and terrible in their own ways. You tell me how the eighties were the decade of confidence and wealth, and I’ll point out how suicide rates were the highest since WWII (a rate not eclipsed until 2018). So even though I was feeling nostalgic and had a yearning to write about my good ole days, the national backdrop of my formative teen years was, in fact, one of paranoia, greed, self-harm, and fear.

Which is great if you’re a thriller writer, because, well, those four things can make for a terrific story. And while a first-person narrative with only a handful of characters may not encompass the full cultural zeitgeist, there are other things about the eighties that can be especially appealing to the thriller writer.

The top of that list is the absence of smartphones. Or even dumb phones. In the eighties, the freedom of being fully untethered while, say, out for a pleasant night drive came at a massive price. One wrong turn, one flat tire, one run-in with an unhinged driver–you were out of luck (the 1986 movie The Hitcher was a brilliant example of this). You had no way of checking your location on a map or calling for help, unless you could hoof it to the closest place with a landline (and who knew what horrors were waiting for you in that place). Writing crime fiction in an area before mobile phones is an unbridled delight, simply because it strips your characters of so many options. Simply put, the more fundamental the technology of an era, the greater ability for all sorts of nasty things to happen to you.

Yet my draw to write about the eighties still came from a place of nostalgia, because I remember those years as some of the best of my life. It was only when I started the process of putting words down that I remembered the cracks in the varnish, the not-so-great bits about the decade. But this ended up saving my manuscript, because as much as the pandemic made me want to write about shiny, happy things, in the end I’m still a writer of dark, psychological thrillers, and there’s nothing particularly fear-inducing about getting the high score in Galaga or moonwalking in front of a school assembly.

The good ole days? Now that I’m in my fifties, I can confidently state they don’t exist. And for a crime writer, that’s a good thing.

***

-

My first novel, For Worse, in bookstores April 2, 2024, is a domestic thriller about a vision impaired woman who’s trapped in a dangerous marriage with a husband who uses her blindness to sabotage her. Desperate for freedom, she finds an unexpected solution in a ladies chat room on the dark web, whose members have a sinister but successful remedy for navigating a bad marriage.

I knew about the domestic thriller genre, but I never realized, till I wrote For Worse, that there was a subcategory called “Marriage Gone Bad.” I thought this was fascinating, and when CrimeReads asked me to come up with my top MGB thrillers, I was ready.

Please note: some of these books involve themes of abuse and/or other possibly triggering subjects, so please do your due diligence and read responsibly.

Gone Girl, by Gillian Flynn, pub. 2012

While I know there had to have been other Marriage Gone Bad thrillers before this (see my next entry), Gone Girl seems like the modern MGB starting point, with its unguessable plot twists, troubling themes and unreliable narrators (I love a good unreliable narrator). This novel sparked my own interest in domestic thrillers, and perhaps is what catapulted the genre into its current ubiquitous incarnation.

The Jealous One, by Celia Fremlin, pub. 1976

A happily married woman suspects that her husband is having an affair with the woman next door, but keeps second-guessing herself, thinking she must be imagining it. Things take a turn when she dreams that she’s murdered the woman, and wakes to find the woman has disappeared. What I love about Fremlin is that she’s very funny, not something you generally find in thrillers. Check out her earlier book, The Hours Before Dawn, about a mum in 1950s London, who’s so sleep deprived from her latest baby, who hasn’t slept through the night in eleven months, that she can’t tell what’s real and what’s hallucinatory. The suspense is palpable, but it’s also hilarious.

Something In the Water, by Catherine Steadman, pub. 2018

A young couple, blissfully in love, go on their honeymoon to Bora Bora and, while scuba diving, discover a bag full of money and jewels. Their marriage unravels as they decide what to do with it. This provides the requisite psychological twists and turns but is also quite witty, which is always a plus for me. I found the heroine, who’s first seen irritably digging a grave, very snarky and fun.

The Silent Wife, by A.S.A. Harrison, pub. 2013

This is a slow burn of a novel about two partners, never married, whose twenty-year relationship has long been faltering: he’s chronically unfaithful and she pretends not to know. When he finally leaves her and she learns that, because they were never married, he has no financial responsibility towards her, she decides to take an extreme tactic. This is less a twisty-turny page turner and more of a “Geez, what would I do?” book, but there’s still plenty of nail-biting moments.

The Family Remains, by Lisa Jewell, pub. 2022

This is a sequel to The Family Upstairs, following the lives of the children in the aftermath of their traumatic childhood. This is a tale where many different strands from the past come together to inform and heal the characters in the present, something Jewell does brilliantly. There is a Marriage Gone Bad amid the strands, and it’s horrifying, but it’s only one part of a complex and compelling story that, like most Lisa Jewell novels, you can’t put down.

Rock Paper Scissors, by Alice Feeney, pub. 2021

Married for ten years, their marriage straining under secrets and lies, a couple goes to a remote getaway in Scotland for their anniversary, to give their marriage one last chance. Part haunted house story, part thriller, part rumination on love and trust, this novel has at least one surprise that even a veteran domestic thriller/MGB reader like me did not see coming.

The Echo Wife, by Sarah Gailey, pub. In 2021

The heroine of this sci-fi thriller is a renowned scientist in the field of cloning, whose husband has used her ground-breaking research to clone himself a more compliant version of her. This is a brilliant, dark and troubling novel that, now that I think about it, I’m going to read again.

Wilderness, by B. E. Jones, pub. 2021

In the interests of disclosure, I have to report that I haven’t yet read this, but I saw the excellent limited series on TV and I’ve ordered the book. A newly married wife discovers that her husband has been having an affair, and agrees with his ostensibly repentant suggestion that they go on a road trip across the US to rekindle their love and trust. This sounds like a good plan, except she can’t forgive him and wants to kill him. It was a great watch and I expect it’s a great read as well: simple, logical, extremely well done, and compelling.

Behind Her Eyes, by Sarah Pinborough, pub. 2017

A single mom meets a man in a bar who turns out to be her new boss, a married psychiatrist, so they initially don’t act on their mutual attraction. Later, his wife, unbeknownst to him, strikes up a friendship with the single mom, who believes the wife has no idea that the single mom and the husband are dancing around an affair. This triangle has enough sizzle to keep it going on its own, particularly since the single mom hears from both the husband and the wife that the other is unstable and making their life miserable. However, Pinborough adds a very strange twist that, when you first read it, makes you think, “Wait–what???” but she’s so good that two seconds later you’re fine with it. This MGB thriller is a high wire act that Pinborough pulls off with aplomb. I saw it on TV as a limited series and then read the book. Neither disappoints.

Our House by Louise Candlish, pub. 2018

A woman comes home from a few days away to find that another family is moving into her house, which wasn’t even on the market when she left. This disorienting beginning (typical of Candlish’s books, all of which I love, whose jumping off points seem to be quotidian “what-if’s”) kicks off a masterfully plotted novel of lies, betrayal and deception that kept me up way past my bedtime.

There are so many fabulous thrillers out there, marriage gone bad and otherwise, that readers can be assured that if one novel doesn’t scratch their itch, the next one probably will. May your next great read (and I hope it will be mine!) keep you up way past your bedtime!

***

-

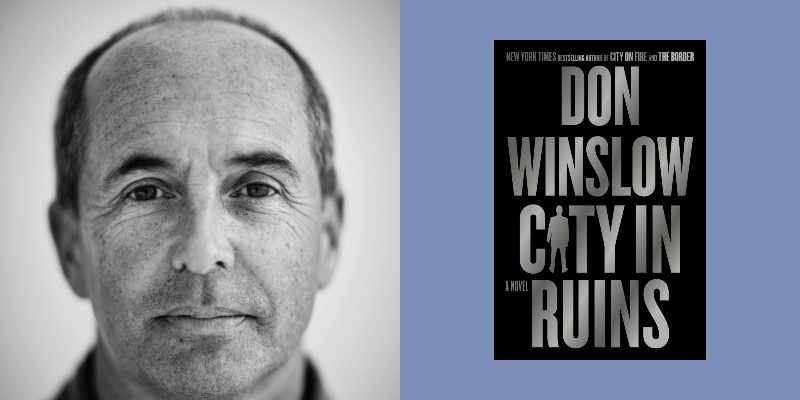

For more than three decades, Don Winslow has written bestselling novels about everything from the War on Drugs (with his sweeping Border trilogy) to police corruption (“The Force”) to mafia hitmen (“The Winter of Frankie Machine”). Yet even as he produced these books at an astounding rate, his muse kept directing him back to a sweeping epic set among the gangs of New England in the 1980s and 90s.

That epic eventually manifested as a trilogy, concluding with the imminent release of “City in Ruins.” When this latest book begins, protagonist Danny Ryan has become a major power player in Las Vegas. He’s a long way from the Rhode Island gang war that powered “City on Fire,” the first book, as well as the Hollywood backstabbing and catastrophe that marked “City of Dreams,” the second. But like the heroes of all epic tragedies going back to the Greeks, hard-working, fast-moving Danny can’t achieve the velocity necessary to escape his past—an intense rivalry with another mogul on the Strip devolves into death and destruction, threatening everything he holds dear.

If you’ve followed Winslow’s career, you know that “City in Ruins” is his last book before retirement. For fans, that makes its imminent release bittersweet. To mark the occasion, Winslow chatted about the trilogy, his career… and whether there’s any chance he’ll reverse that decision to retire.

The Danny Ryan trilogy is set in the 1980s and 90s, and bounces between Rhode Island, Hollywood, and Las Vegas. What made you decide on that particular time period as opposed to modern day, or even the 1950s and 60s?

Several reasons.

The 50s and 60s have been done, and done so well, in iconic works such as, obviously, “The Godfather.” There was no point in my retreading that ground.

Second, I wanted the trilogy to end in Las Vegas in the 90s because I wanted to come in after the major power of the mob was over. The 50s and 60s in Las Vegas were obviously fascinating, and rich ground for a writer, they’ve also been done. I wasn’t that interested in covering the era of the Rat Pack, or even of Lefty Rosenthal and Tony Spilotro. I am very interested in transitional eras, such as Las Vegas in the years when corporate money was taking over but when there was still a residual mob influence. That seemed the most interesting time to bring Danny in.

Third, I wanted direct access to the years I was writing about through the whole trilogy. That is, I wanted a time within my own memories and experiences. I knew Rhode Island, Hollywood and Las Vegas in those years. They were evocative for me in a way that made them… not easy, but powerful… to write. Also, that period allowed me to talk to people who were there, which was invaluable.

You’ve been writing this trilogy, on and off, for three decades. When you started out, did you have a detailed idea of the plot and character arcs, or were those things that developed gradually as you worked over the years? In the end, did the final versions of the books differ radically from your initial vision?

Well, in a project that took almost thirty years from conception to completion, things are going to change. Having said that, the overall concept—to create an epic that would be a standalone, modern crime saga while also a retelling of Greek and Roman classics—never changed. What developed gradually were the specifics. While I always knew, for instance, that Danny Ryan would stand in for Aeneas, and that the general arc of his story would track the “Aeneid,” the details of how to make ancient events truly modern were challenging, and the solutions did change over the years as I got better ideas. It took a whole lot of bad ideas to get to the good ones, and I’ll bet I hit ‘delete’ on literally hundreds of pages. Some of the developments were surprising—for instance, I didn’t expect Danny’s mother, Madeleine, to become such a major character, but in researching and writing her I became fascinated. It happens that way sometimes.

I knew that Danny would have to build an empire, but it was a big question as to what that could be in the 1990s. A drug empire was too easy a solution—there had to be something better. I finally hit on Las Vegas and the gambling industry. I’m a little embarrassed that it took me years to hit on that. But once I did, the third book, “City in Ruins,” became possible. And once I hit on the idea that the central conflict would be over a valuable piece of real estate (not a woman, as in the “Aeneid”), the book really took off.

The trilogy is also an extended riff on classical literature. The first book, “City on Fire,” recalls “The Iliad”; the second, “City of Dreams,” echoes a big chunk of “The Aeneid.” With “City in Ruins,” where do we stand in terms of the parallels to epic poetry? (While I was reading the end of your trilogy, I was also listening to the audiobook version of Emily Wilson’s translation of “The Iliad,” and I was really struck by how certain themes—honor, vengeance, carrying your people through hardship—have endured over the centuries.)

“City In Ruins”—which, as in the whole trilogy, can be read with no reference to the classics at all—tracks the last third of the “Aeneid,” the last books of the “Odyssey” and the final play of the “Orestes” trilogy by Aeschylus. My goal was to create an entire world, peopled by modern, approachable characters, from those epics. Initially, I intended to do only the “Aeneid” and Danny, but, again, I found some of the ‘secondary’ characters so interesting that I wanted to tell their whole stories.

Picking up on your comment on enduring themes, that was the impetus for the whole trilogy. When I started to read the classics, I was struck at [how] their themes still remained relevant in not only contemporary crime fiction, but also in real-life crime history. I already knew the Helen of Troy story from things that were happening around me when I was growing up. I felt that I already knew these characters, these people.

When we consider the origins of modern crime fiction, we always—as we should—look to Chandler, Hammett, Christie, Doyle, et al., but I think that we look for our roots in too shallow a soil. We should also look at Dickens, Shakespeare, Cervantes, and yes, Homer, Virgil and Aeschylus, because, as you mentioned, those themes of honor, vengeance, loyalty, revenge, power, lust and love have never changed. If you shot some of their stories in black and white and put a trumpet score behind it, you’d have a noir film.

Much of “City in Ruins” takes place in Las Vegas, which is the setting of many a gangster epic (as well as an incalculable amount of real-life gangster drama). Knowing that, how did you approach Danny’s story in Vegas so that it stands out from all the gangster/business intrigue stories that have come before?

Mostly by setting it in a specific era, that is, when corporate money had taken over from organized crime. I thought there was a seam in there that I could mine without being in the shadow or stepping on the toes of such great works as “Casino.” I know my Las Vegas crime history pretty well—I wrote about it at length in a book called “The Winter of Frankie Machine,” and I didn’t want to repeat that.

I think that empires are at their most interesting at two points—when they’re on their way up and when they’re on their way down, and this period gave me the chance to write about both. I also liked the societal commentary that it provided. To paraphrase Shaw, “Any vice that society can’t control it turns into a virtue,” and that is certainly the case of Las Vegas and the gaming industry as a whole. ‘The numbers’ used to be a crime, now buying a state-run lottery ticket is a civic-minded act. Las Vegas has come to pride itself on being squeaky clean as regards its gambling operation, but it can no more escape its past than can Danny Ryan. There will always be that taint, that, let’s be honest, seductive scent of criminality about it that they even use in their marketing—“What happens in Vegas… .” So I was interested in that transition, how a guy like Danny could navigate both the city’s and his own attempted changes. I think that’s what sets the book apart.

I know any number of crime writers would like to take a shot at writing an epic trilogy. You’ve now done it a few times. Do you have any advice for anyone who’s contemplating spending years of their life on writing a sweeping tale across multiple volumes? I assume your approach for the Danny Ryan trilogy differed from the Border trilogy, for example, just given the sheer amount of research you needed to do for the latter, etc.

Well, I’d tell them to get ready for a marathon. And to understand that it’s life-changing. Other than my wife and son, I have spent more time with Danny Ryan and Art Keller (the protagonist of my other trilogy) than any other real human being in my life. So know that it’s a marriage—you’re going to go to bed and wake up with the same person for decades. I spent 23 years writing about drugs—it changed who I am and how I view the world. I spent close to 30 years wrestling with the Danny Ryan trilogy, it took my going home to Rhode Island and seeing it in a different (more mature?) way to really be able to write the book.

What I would advise above all else is patience. Know that there are going to be good days and bad days on the books, and know that the bad days are absolutely necessary. Those wrong ideas, those crappy pages are an essential part of the process that you just have to go through to get to the good stuff.

I’d also advise flexibility. Don’t get too rigid, too stuck on an outline. Be open to possibilities, go on tangents, because sometimes they’ll open you up things you hadn’t planned or even thought of, and they’re often better than what you had.

You’ve said this will be the last book before you retire. As you look back on your career, if you had to condense your books to a set of themes, what would those be? Throughout your books, your characters inevitably seem to discover there’s a price to whatever they’re doing or desiring. You also tackle everything from the morality of criminality to U.S. policy failures. Is it impossible to condense it down?

Yeah, it’s impossible.

But if you put a gun to my head (I am, after all, a crime writer), I’d say that the central theme that runs through all my work is what I think is the essential question of crime fiction—how do you try to live decently in an indecent world?

When I look back on my career (a relatively recent activity for me) I think that all my main characters have struggled with that issue, whether it was Art Keller trying to reconcile the conflicting morality of the War on Drugs, or Denny Malone navigating the complexities of a cop’s life, Frankie Machine trying to justify his career as a hit man, or Danny Ryan attempting to to raise a family in the midst of a mob war, I think it’s all been about trying to find a morality, or a redemption, in a world that doesn’t care about either. Maybe it’s my Catholic childhood, but those have always been central questions to me, for individuals, societies, even nations. How do we exist decently?

If I find the answer, I’ll let you know.

When you talked to CrimeReads about “City of Dreams,” you seemed pretty adamant about retirement. Is that still the case? As the 2024 election cycle gears up, do you plan on pouring your time into political messaging?

It is still the case.

Look, do I have mixed feelings about it? Of course I do. The readers out there have given me a career and a life that I couldn’t have dreamed of. So I’m grateful. And humbled. And of course I’ll miss it. I already miss that routine of getting up before dawn (okay, I still do that most mornings), making that pot of coffee (ditto) and going to work on a novel (ah, there’s the difference). That was my life.

But we don’t get to choose the times that we live in, and we live in a time in which our democracy is in an existential crisis. That demands our time and energies.

So yeah, watch this space.

-

Write what you know—it’s a piece of advice you hear a lot. I’m not sure how useful it is. My first novel opened with a mysterious man buying a shovel so he could help a friend dig a grave in the woods. My latest begins with an eleven-year-old girl sneaking out her bedroom window for a walk under the stars and stumbling across the body of a serial killer’s victim.

I’ve never found myself in either of those situations.

But when it comes to choosing a setting for a story, writing what you know has its benefits. For my new novel Don’t Turn Around, I wanted to use a small college town as the setting—somewhere rural and remote. A place where my serial killer, known as Merkury, could take a college student as his twelfth victim. A place where my protagonist, Kate Summerlin, all grown up now at twenty-nine, could go to track the killer down and come to grips with what happened to her when she was eleven.

I knew the perfect spot, because I grew up in upstate New York and went to college at Colgate University in a small town called Hamilton. I knew the campus on the top of the hill, the academic buildings with their stone facades, the movie theater downtown. I changed a few details and Colgate became Seagate College. Hamilton became Alexander. The back roads and woods on the outskirts of the town became places where a serial killer could operate.

Write what you know.

Like anyone who writes, I owe a lot of what I know to the work of others. So here are five crime novels that have entertained and influenced me—all of them set in college towns.

First Lady by Michael Malone