-

Posts

4,576 -

Joined

-

Last visited

Posts posted by Admin_99

-

-

1 hour ago, aawoods said:

Sounds similar a certain Star Wars movie that was notoriously ill-received....

For the record, I agree that some plotting is inevitable. Even so-called "pansters" must have the general arc in mind, or at least the preexisting twists for a satisfying story, right? How else would Martin have planned the *SPOILERS AHEAD* Hodor scene, or the reveals of various character heritages, or the end-goal of Dany's descent into madness? As much as Martin, like King, talks about eschewing plot for natural character development, in some ways those characters are still on tracks that stem from their backstories. Is that not plot?

Excellent points! You really nailed it though with the character backstory observation.

-

One last thing, if every early stage novel writer possessed the time-honed story instincts of Stephen King, a bit more pantsing might be in order, however, they do not.

-

I still maintain the whole pantsing thing started with Jack Kerouac's publicity stunt for ON THE ROAD.

Dramatically speaking, you cannot have a protagonist or an antagonist without a plot, because outside of that context, they don't exist. You can't work from a high-concept premise without a plot. Plot evolves from the concept naturally OR IT'S NOT A STORY CONCEPT. The very basics of genre novel storytelling are PLOT BASED, naturally with a slew of characters interweaving and helping to define and push it forward. When you pitch, you don't pitch character traits, you pitch plot including the inciting incident and first plot point at a minimum.

King novels have PLOT, no question. So he throws characters in bowl and plays pantsing games with them for a few days (or so he says, though his MISERY reflection totally contradicts that) or whatever, then a story emerges, BUT that story has a plot! It's inevitable, or there is no story. Personally, I think he gets the bulk of his story ideas from various sources, as he did with MISERY, but I'm sure it's a mixed bag. Whatever suits him at the time.

But he can't maintain with any degree of validity that authors can't acquire great story ideas ahead of time, by whatever means, and work from there to flesh out the plot to conclusion. He already admitted he did just that with MISERY.

Even novel writers with advance outlines, in one form or another, realize fluidity as the story moves forward due to the characters coming alive on the page. But a plot plan equals GOALS. Again, if the goal is to retake the mining station on Ceres, a side trip to the slave moons of Jupiter for no good reason (or that would be PLOT) just because X character decided it was a good idea, might not work so well for the story as a whole.

A writer must keep their vision on the overall premise and the time-tested best storytelling ways to get there. This will prevent arbitrary character coups on the page that throw the story out of kilter and lead to rejection slips.

-

The New Yorker editor reached Randy Wayne White at his historic waterfront home high atop a historic Indian mound on Pine Island on Florida’s Gulf Coast.

“We’d like you to write a story about the Everglades for us,” she told him over the phone.

Randy was in a foul mood. The Outside magazine columnist was also a fishing guide working out of Tarpon Bay Marina on Sanibel Island, just across the bay and salt flats from his home, and it was the height of fishing season.

“I’d been fishing something like 48 days straight,” he says. “So much has been written about the Everglades, I don’t know of anything else to write.” He told her thanks, but no thanks.

He went on with his business: by day guiding his fishing clients to the best underwater neighborhoods in the Gulf of Mexico, and in the early morning hours writing columns and feature stories that give you sunburn. The New Yorker editor did her equivalent: attending Manhattan literary parties, chumming for talent and telling editors: “Randy White’s pretty good, if you can get him.”

In economics there’s supply and demand. Where those two curves meet is your price point. Randy was the supply, and his demand curve—now driven by the mystique of the literary party circuit—had risen sharply. He was already making—and this was in the late 1980s—$13,000 a month for a 1,000-word column in Outside magazine. Thanks to word of mouth and the cache of Outside magazine, other magazines started calling.

But even with his experience as a back-country fishing guide, he was determined to never write a feature on fishing. “I didn’t want to become known as a fishing writer.” Randy had a thing for the written word as well as for managing his career, which lead him into the world of writing books, but not immediately.

“I fell in love with books at an early age,” he says. “I thought if I could write one, I could come upon the magic I found in books.”

But first, this Southwest Floridian had to make a living. One of his first jobs was as a telephone linesman climbing poles, which made it possible to call anywhere in nation for free while dangling 30 feet above the ground.

“I called the News-Press from a pole and it was cold.” He had no experience and no education in journalism, but the Fort Myers, Florida newspaper—which had just been purchased by Gannett and was expanding—hired him. There, he honed his craft, first as a reporter traveling to small towns to write features and then as a daily columnist.

He later became a fishing guide, but never gave up writing. He would rise at 4 a.m., write for a few hours, and then meet his clients at the marina for a day’s fishing on the Gulf of Mexico.

In 1977 he sent an unsolicited story to Outside magazine’s Editor Terry McDonell. The story was rejected but McDonell was so impressed by his writing he hired him as a freelancer, which later turned into his regular monthly column.

“When I started writing for them, it was harder to get a major assignment from Outside than it was to publish a book.” And as he would quickly learn, magazines also paid better.

In the early 1980s an editor with New American Library was looking for writers to contribute to a new thriller series and asked if he would be interested in writing books under contract. The protagonist had to be blond, work in Key West, be freakishly strong, well-hung and had to know Hemingway.

“I wrote the entire book on iced tea and Red Man chewing tobacco in nine days,” he says. “As I recollect there were some nice sentences in it, and I was excited when I got the first copy.”

The Key West Connection by Randy Striker was published in 1981.

“I think the other fishing guides were impressed.”

New American Library was so happy with his speed that the editor asked if Randy could do it again. When he said yes, the editor fired three other writers she’d hired to contribute to the series and left if solely in Randy’s hands.

He wrote six more novels under contract for $5,000 each, always using a pen name. “They were awful,” he says, “and riddled with clichés. But the writing has held up, apparently. All of them are still in print and selling remarkably well.”

“I should have been writing my own books. I felt such self-contempt, but it was a good learning experience.”

Randy is a big man with massive biceps and a shaved head, something that appears more appropriate for the World Wrestling Federation than the literary world. There is no bullshit about him. He’s straightforward and candid, especially about himself. He talks about those in the business who piss him off and is open about his own ego, strong will and work ethic. While it’s the perfect mix of self-awareness and discipline for a writer, it’s unusual to talk with someone so genuine speaking with a stranger.

“I’m driven. Actually driven,” he admits.

He is also beloved. We met at Doc Ford’s Run Bar and Grill, his restaurant named after his famed protagonist and located on Sanibel Island. It is one of four restaurants owned and operated by his partners (Randy owns the franchise.). He lives on the island in seclusion. He became so popular that his home on Pine Island, which he still owns, was overrun by tourists. During our two-hour conversation he is constantly interrupted by fans seeking his autograph. He graciously complies.

Randy is not the type to fall prey to his public image as a famous author, which brings up his experience with the late gonzo journalist Hunter S. Thompson. First, Randy makes clear they were acquaintances, not close friends.

He first met Thompson in 1970 when Thompson was running for sheriff of Pitkin County, Colorado and Randy was a contract phone installer and lineman. Years later, when he was a well-known author, Randy dropped by Thompson’s home in Woody Creek. Thompson’s first words on seeing Randy’s hulking presence after so many years was, “Jesus Christ, you’re even scarier looking than people say.” They spent the evening talking. From then until he committed suicide in 2005, Hunter would call Randy at home in the middle of the night, always with questions about Florida. They still have many mutual friends.

“He was a funny, delightful guy. Clearly brilliant,” Randy says. “Tragically, he just got involved in his own caricature.”

As a magazine writer Randy recalls, “One of the best gigs was Playboy. They’d call me if they had a ‘Playmate of the Year’ in Florida. I’d sit down with her and write the hand-written page and photo captions.” He also wrote feature stories for the magazine.

When his editor at Playboy was about to take the helm of Men’s Health magazine, Peter Moore wined and dined him and made him an exclusive financial offer that was even better than his monthly column at Outside. Seeing a promising opportunity, Randy reluctantly jumped ship and started writing a man’s-man column called “Guys Like Us” for Men’s Health. The editors were blown away by the positive reader response.

“We’ve never had a reaction like this. Keep doing what you’re doing,” they told him.

Unfortunately, he too soon was blown away—by their repeated meddling in his writing. His column became “a diluted, corporate-crafted mess.”

“I had a one-year contract. Peter Moore told me later, ‘I’m the one who drove you out of the magazine business—you should thank me,’” Randy says, “Peter was right, and I still like him a lot. The others involved were well-intended amateurs. A columnist can’t write by committee.”

Throughout his writing career, he says, the Men’s Health episode was “the only unpleasant writing experience I’ve had.” Elsewhere, he says, “I’ve had some incredible editors—particularly at Outside and Men’s Journal—who saved my ass more than once.”

As soon as his contract expired, he quit and walked away from an unhealthy, but substantial, part of his income.

And then the unthinkable happened. The federal government decided to close Tarpon Bay to powerboat traffic. Overnight, White was facing a future with no income and a family to feed.

With two young sons, he did the one thing he knew how to do—write. This time, he would try a novel under his own name. “It had to be good. I wanted the book to be lyrical, even literary, but appeal to the commercial market. Failure wasn’t an option.”

He’d traveled to Central and South America for various magazine stories and fishing outings. Using that knowledge and his background as a fishing guide, he created a realistic story with his protagonist Doc Ford, a marine biologist who lives—where else—on the water in a marina on a fictionalized Tarpon Bay (Dinkin’s Bay in Randy’s novels.)

“Much of it is accurate in terms or description and the plot line—and certainly one of the bad guys,” he says.

He worked day and night and completed Sanibel Flats in seven months. He mailed a paper copy to Robin Johnson, an aspiring agent in New York, who was the daughter of one of his charter clients. Within two weeks, she called back with an offer from St. Martin’s Press for a three-book deal at $5,000 a book.

“I told her I make more than that on magazine stories.” But he signed the contract anyway. He needed the money.

Sanibel Flats was published in 1990. Randy was 39 and finally, a book with his name on the cover was sitting on bookstore shelves and did nothing else.

“It got incredible reviews, but it didn’t sell worth a flip.” So, he found another gig as a fishing guide to shore up his income. Sadly, his next two books suffered the same fate as his first: great reviews, piddling sales.

Still, St. Martin’s offered him another three-book deal. But at about the same time, Neil Nyren, Editor-in-Chief at Putnam, called out of the blue after reading one of his novels and signed him to a three-book deal over the phone and guaranteed him $80,000 a book. Shortly after, he signed with mega-agent, Esther Newberg, vice president of ICM Partners.

“I thought I was rich. I had no clue I’d just caught a damn-near perfect wave.”

Since then he has been a regular on the New York Times bestseller list. In 2001 the Independent Mystery Booksellers Association named Sanibel Flats one of the “100 Favorite Mysteries of the 20th Century.”

Randy has also received the Conch Republic Prize for Literature and the John D. MacDonald Award for Literary Excellency.

His PBS documentary, “The Gift of the Game,” which he wrote and narrated about bringing baseball to Cuba, won the 2002 Woods Hole Film Festival “Best of Festival” award. A catcher since high school, Randy played senior league baseball in Florida on teams that included several ex-Major League players. “I’ve caught a lot of great pitchers,” he says, “including three Hall of Famers.”

During his career he has written dozens of novels and non-fiction books and is working on his third in his “Sharks Incorporated” series, which targets young adults. He’s written for National Geographic Adventure and is still an editor-at-large at Outside magazine.

“The wonderful thing about writing…editors don’t care if you went to college or not. (Randy didn’t.) Or if you’re a man or woman…You don’t apply for a job as novelist. You don’t do interviews. You don’t have to take a test. It’s a pure free market. It’s all about what the individual can do.”

He writes six hours a day, seven days a week. When he comes to the end of a manuscript, he has a long-standing tradition with his two sons, Lee and Rogan. Since they were children, he’s let them come up with the final two words of each manuscript and type them on his aging Underwood. At the end of each author’s note in his novels he thanks them for helping him finish the book. This is the one time he doesn’t mind someone meddling with his copy. It goes without saying, he likes these editors. Maybe they’ve saved his ass too.

This time he’s happy to give them the last word.

___________________________________

Sanibel Flats

___________________________________

Start to Finish: Seven months

I want to be a writer: 11 years old

Decided to write a novel: 1989

Experience: Magazine columnist, feature writer, fishing guide, adventurer, contract novel writer

Agents Contacted: One

Agent Rejections: None

Agent Submissions: One

Time to Sell Novel: 10 days

First Novel Agent: Robin Johnson

First Novel Editor: Sally Richardson

First Novel Publisher: St Martin’s Press

Age when published: 39

Inspiration: Joseph Conrad

Website: RandyWayneWhite.com

Advice to Writers: Be relentless. Be absolutely relentless. For me learning the craft was a very slow learning curve. Learn to be merciless as an editor.

___________________________________

Like this? Read the chapters on Lee Child, Michael Connelly, Tess Gerritsen, Steve Berry, David Morrell, Gayle Lynds, Scott Turow, and Lawrence Block.

—From “My First Time,” an anthology in progress by Rick Pullen. rickpullen.com

-

(This article contains spoilers for Psycho and Les Diaboliques. And The Sixth Sense.)

This year marks both the 60-year anniversary of Psycho and the 65-year anniversary of Les Diaboliques. Psycho, directed by Alfred Hitchcock, has become one of the most famous movies of all time. Its brutal murder in a shower and its jolting all-strings score by Bernard Herrmann have acquired the status of memes. Even people who haven’t seen the movie have mimed stabbing movements while emitting staccato screeches to evoke the idea of a psychopath.

Les Diaboliques, made 5 years before Psycho by French director Henri-Georges Clouzot, isn’t as well-known these days, though we might not have Psycho without it. In the early 1950s, Hitchcock was desperate for the rights to the novel on which Diaboliques was based, but Clouzot ultimately won. People have speculated that Psycho was Hitchcock’s attempt to outdo Clouzot. There are certainly parallels within the movies: both are set in creepy collective living spaces (a boarding school, a motel), both depict grisly murders in bathtubs, and both end with a mind-blowing plot twist that pulls the rug out from under us. It’s this last part I want to focus on.

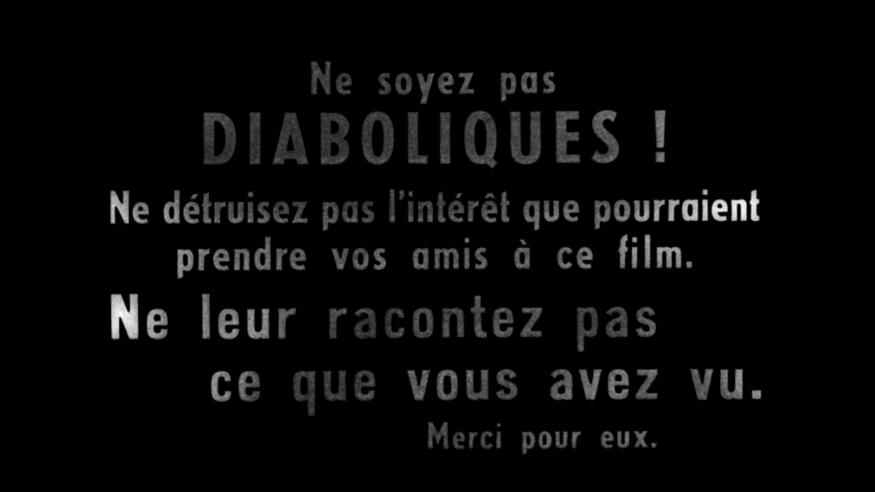

At the time of their release, both movies worked hard to protect their twists. After announcing “The End,” Diaboliques sent viewers out into the world with a disclaimer:

The final disclaimer:

Don’t be DIABOLICAL!

Don’t destroy the interest your friends might take in this film.

Don’t tell them what you’ve seen.

Thank you on their behalf.

Five years later, movie theaters screening Psycho were instructed not to let anyone enter the movie late or leave in the middle, and in some (perhaps apocryphal) cases stationed ambulances outside to tend to viewers overwhelmed by the ending.

All this elaborate management of the audience’s experience seems to confirm the widespread assumption that plot twists are just one-shot disposable tricks. So then why do Diaboliques and Psycho still hold up more than half a century later? Why do they continue to astonish first-time viewers and delight returning fans? Whether you’ve watched one or both or neither of these movies, I want to persuade you that they’re both absolutely worth watching (again) now. Why? Because Diaboliques and Psycho both achieve something very rare: a perfect plot twist but an unspoilable movie.

A plot twist is a machine for sudden dizzying reinterpretation. Bruce Willis is really a ghost! With a lurch we realise that we knew so much less than we thought, but can now look back and see a string of clues hiding in plain sight. The metaphor of having the rug pulled out from under us captures the sense that what we thought was firm ground was in fact a ruse to wrong-foot us. A good plot twist blows our mind by playing on what we know, and what we only think we know. In this way, it transforms an audience’s ignorance and misunderstanding—hardly promising material—into a source of delight.

Diaboliques and Psycho‘s plot twists do this, but they also do more: they consistently invite us to feel an intense (but misplaced) knowingness. By knowingness I mean the way having knowledge makes us feel. Knowledge can make us feel smug and self-satisfied or serenely superior, or it can fill us with anxious dread or agonising anticipation. These movies let us in on massive secrets (murder! crime!) early on, so that we feel like insiders and watch scenes where other characters fail to uncover those secrets. But we fail to realise, until it’s too late, that the movie is keeping other, bigger secrets from us.

* * *

Diaboliques begins with a bad man flaunting what should be secrets. Michel (a slimy Paul Meurisse) is the bullying headmaster of a boarding school near Paris. He’s openly having an affair with Nicole (Simone Signoret looking like a proto-Hitchockian icy blonde), one of the schoolteachers, making no attempt to hide this from his wife Christina (played wide-eyed and shawl-clutchingly by Vera Clouzot, the director’s wife), also a teacher at the school. Even worse, Michel is physically violent and psychologically abusive towards both women. He gives Nicole a black eye and torments the fragile Christina, who suffers from a heart condition, making her eat rotten fish in front of the entire school. Michel’s abuses are publicly known, while the women must keep up appearances.

We experience events from Christina’s perspective, and once she and Nicole are alone together we discover they’re better at keeping secrets. Nicole proposes a secret plot to Christina that will end Michel’s abuses permanently: murder! The women lure Michel to an apartment in Nicole’s small home town, where he hits Christina and then angrily begins drinking the whiskey which the women have knowingly spiked with a sleeping tincture. Before long, Nicole is filling the bathtub with water and holding Michel’s drugged body under the water with remarkable sangfroid while the more sensitive Christina looks away in horror.

The next day they drive the waterlogged body back to the school, and at night roll Michel’s body, now with eyes grotesquely glazed, into the school’s swimming pool. Eventually the body will float to the surface, and it will seem like Michel drowned accidentally in the school’s pool while the women were hundreds of miles away.

But the body doesn’t resurface. The pupils and other school teachers begin to speculate about Michel’s absence, while we share the women’s dark knowledge of what really happened. Nicole fake-accidentally drops a set of keys into the pool, and when the janitor drains the pool Christina looks in and faints in horror—not at the sight of a decaying corpse but because the body isn’t there! Like Christina, our knowingness is first shaken and then shockingly undercut. The vanished body suggests there are further secrets of which the women were unaware. (In contrast to Christina and first-time viewers, returning viewers might be starting to full smugly knowing here.) Nonetheless, we’re still aware that we know more than the school pupils and teachers: we know why Christina has fainted, we’re in on her and Nicole’s secret at least.

Then, strange occurrences begin to pile up. The suit Michel was wearing that fateful night is delivered to the school by a local dry cleaner. A school photograph is taken and seems to have captured Michel’s face in the gloom of a window. A young schoolboy smashes a windowpane with his catapult, and obstinately insists Michel returned to punish him. Is Michel acting from beyond the grave? Did someone take the body in order to blackmail the women? Are their minds playing tricks on them?

“I saw him, I did, I know I saw him”

Still, for all these mysterious new questions, we’re still in on the secret of the women’s murder plot. Privately, though, they begin to unravel. Christina in particular seems to be crumbling under the guilt and anxiety, which in turns makes Nicole increasingly irritable. We share the women’s grim irony as they have to listen to patronizing mansplaining that isn’t even aware of how much it misses. A detective appears on the scene, and the discrepancies in knowledge start generating not only irony but tension: we watch anxiously along with Christina and Nicole as the detective paces around the school, asking questions and noting details that might reveal the women’s murderous plot.

Christina becomes increasingly unwell, and a doctor orders her to stay in bed due to her heart condition. That night, at the movie’s climax, Christina is drawn from her bed by strange noises and shadows. Lured into the bathroom, she turns to see Michel’s body once again submerged in a bathtub.

Christina falls to the ground gasping. As if in a nightmare, the body begins to move. It rises uncannily, dripping bathwater. The hideously glazed eyes of the drowned man turn towards Christina. She looks back with horror, emits a few groans, and then slumps down dead.

So Michel was seeking his revenge from beyond the grave!

But no—almost immediately the energy in the room changes. Michel pops out a set of white contact lenses, revealing his normal eyes underneath. Nicole enters, they check Christina is really dead—yes, the nightmarish spectacle has given her a long-threatened heart attack. Michel and Nicole embrace and rejoice at the small fortune they’ll inherit now Christina has died of natural causes. All along, we thought Christina and Nicole were in cahoots, when in fact Nicole and Michel were the real allies.

Looking back, we realize that because we saw the murder from Christina’s perspective we never actually saw the entire drowning—while Christina was looking away there was plenty of time for Nicole to let Michel come up for air. Our feeling of being insiders on the women’s secret plot kept us from considering that Nicole might have secrets of her own. If we’d given it any thought, we’d have assumed that the diaboliques—the devilish ones—were Christina and Nicole. Now we discover that the real devils are Nicole and Michel.

So here we have our big reveal—the secret that I’ve been trying to avoid spoiling until now. But the movie isn’t done with its twists yet. When I recently rewatched this movie, knowing this twist, I was disconcerted to find this wasn’t the movie’s last surprise. I rewatched it feeling pretty smug, and then discovered that even my knowledge as a returning viewer was misleading me.

The wicked couple gloat, and we’re briefly realigned with their sense of their own superior knowledge compared to Christina, before that too is undercut. The detective enters and arrests the couple. We feared he would discover the women’s murder plot. Instead he discovered the plot beneath the plot. The architects of the movie’s central plot twist now also experience one themselves.

In this series of dizzying reversals, the movie keeps provoking our knowingness only to undermine it. While the big reveal of any plot twist throws us from the illusion of knowledge into an intense ignorance that leads to a new, superior knowledge, the last few minutes of Diaboliques pitch us back and forth between feelings of ignorance and knowingness so that we’re left exhilarated but unsure what solid ground is even left.

* * *

While Diaboliques ends with twists upon twists, Psycho is a rare example of a story that contains two totally distinct plot twists, one near the start, one at the end, and it uses the knowingness generated by the first twist to set viewers up for the second.

In the first 25 minutes of the movie, we follow Marion Crane (Janet Leigh, seductive with a hint of sadness) as she lounges in bed with her married boyfriend, deals with a sexist boss at the bank where she works, impulsively steals $40,000 cash (around $350,000 in today’s money) and goes on the run. She’s in every scene, her goals propel the action. As she drives through the night to reunite with her boyfriend, she stops to sleep at the Bates Motel.

While checking in, she makes polite small talk with the manager Norman (Anthony Perkins, sweet and over-sincere), who overshares about being trapped at the motel with his mother. We share Marion’s condescension towards this sweet but feeble young man, henpecked by his disturbed mother but too attached to ever leave. And we feel superior because we know about Marion’s secret crime that the wide-eyed Norman couldn’t dream of.

“We’re all in our private traps”

In her room, Marion undresses to take a shower. Norman spies on her through a peephole. Shortly thereafter, the shadowy figure of Mrs Bates enters the bathroom to brutally put an end to a seduction Marion wasn’t even aware of inciting. The now infamous shower scene has begun.

The first twist: Marion isn’t the main character, she’s the story’s first victim.

The shower scene is so infamous that it’s hard for viewers today to experience the initial shock of this twist. But the movie in fact did a lot to set early audiences up for surprise. Like Diaboliques, Psycho invites audiences to misattribute the title to the wrong character. Marion acts recklessly, is visibly rattled and even hears voices as she drives, making her initially the movie’s obvious candidate for psycho status. Add to that the fact that Janet Leigh was the movie’s big star and featured front and center on the poster, and you’d expect to be with Marion for the long run.

(While Psycho‘s first twist may no longer surprise, this type of twist does seem to work afresh for every generation: for some it was Drew Barrymore getting bumped off 10 minutes into Scream, for others it was Sean Bean, the biggest name in Game of Thrones, losing his head before the end of the first season. The site TV Tropes even has a name for this: Dead Star Walking.)

Like Christina in Diaboliques, a character whose perspective we’ve shared is killed by something she never saw coming. Her secret turns out not to be the story’s most important secret. Marion’s secret turns out to be irrelevant, and so audiences being in on her secret is irrelevant too.

But we do have a new secret that drives the plot forward: we’ve seen Norman discovering Mother’s murder and covering it up. For most of the rest of the movie, we align with Norman’s knowledge, even though we don’t root for him: when Marion’s boyfriend and sister come investigating we know where they should be looking for clues, what questions they should be asking. When the local sheriff reveals that Mrs Bates is dead and buried, we know that there’s been some trickery as she’s alive and kicking (and stabbing) at the motel. Our knowingness kicks in once again, but this knowingness isn’t tinged with smugness so much as with frustrated impatience—no, don’t go in there! figure it out already! (And if you know what revelations are ahead, this investigation phase feels doubly frustrating.) Scene after scene, the knowledge we share with Norman feels agonizing.

Which brings us to…

The second twist: Mrs Bates really is dead, but the murderous Mother is a split personality in Norman’s mind.

There’s a deeper secret behind the secret we thought we knew, and that the characters needed to uncover. The real psycho is the sweet young man nobody would ever suspect (though he did have that weird interest in taxidermy…).

As with Diaboliques, we thought we were in on the secret of a murder and coverup, and were waiting to see if others would discover it. In fact the knowledge we shared with one of the characters bamboozled us, as it did them. In Diaboliques, Christina was the victim of a plot within a plot, her partner in crime secretly scheming against her. In Psycho the added complication is that Norman is keeping a secret from himself, one part of his mind is plotting against another. We thought knowing what he knew put us in a position of superior knowledge, when in fact it led us to misunderstand the situation as tragically as he did.

* * *

Both Psycho and Diaboliques manipulate feelings of knowingness throughout, culminating in the intense revelation of a whole series of misunderstandings at their denouements. Despite suddenly revealing audiences’ misunderstanding, plot twists usually leave us with a firm sense of certainty at the end. They eventually reveal all the truth, and give us a powerful new interpretive framework that perfectly makes sense of what came before. But that’s not quite how it works in these two movies. After the big reveal of the plot twist, both movies end with a brief flourish that isn’t a full-blown twist but does unsettle our knowingness one last time.

After the double reveal at the end of Diaboliques of Michel and Nicole terrorizing Christina to death, and the detective catching them in the act, we cut to the next morning. The young schoolboy with the catapult smashes another windowpane, and when a teacher asks how he got the catapult back the boy says Christina gave it back to him. The teacher admonishes him that Christina has died, to which the boy simply replies “she isn’t dead, because she came back”. The boy is sent to stand in the corner, as he obstinately repeats “I saw her, I did, I know I saw her”. Fade to black, “The End.”

“I saw her, I did, I know I saw her”

In the moment, it’s hard to know what to make of this final scene, because its significance depends on how we understood earlier scenes that have, just in the last few minutes, been cast in a totally new light. When the boy claimed earlier to have seen Michel, we (thought we) knew Michel was dead and so assumed the boy must either have been tricked or actually seen a ghost. Now we know that he really did see Michel alive. So does that mean he has really seen Christina too? Is she alive, despite what the teacher says? Is this yet another ruse? Is she the movie’s first and only real ghost? The movie doesn’t give us enough evidence—or time—to come to any conclusions.

And even that isn’t quite the end of Diaboliques. Remember that final disclaimer? “Don’t tell them what you’ve seen.” It might seem like a simple instruction, but placed alongside “I saw her, I know I saw her”, the movie reminds us one last time of what it’s repeatedly demonstrated: that seeing may be believing, but it’s not necessarily knowing.

Psycho too, after the big reveal, ends on a note of uncertainty. First a psychiatrist confidently explains Norman/Mother’s psychology in terms of repression and guilt, before we move into the jail cell and hear Norman/Mother’s crowing at having misled the psychiatrist. Each claims to know more than the other, and we have no way of knowing who’s right.

“Why, she wouldn’t even harm a fly…”

So yes, while it’s a spoiler to tell your friends that Nicole is secretly in cahoots with Michel against Christina or that Norman and Mother are the same person, in their final moments these movies raise new doubts about the solid ground we finally felt we’d reached.

I’m reminded of a moment from Friends in which dopey Joey is told not to reveal anything about a pileup of secrets, bluffs and double bluffs, and he responds “couldn’t if I wanted to”. The dizzying twists of Diaboliques and Psycho resolve into new mysteries that—even if we wanted to—we couldn’t spoil

Whereas most plot twists create a vast difference between the first and subsequent experiences, these two movies make viewers’ knowingness (generating it, undermining it) an integral part of every viewing experience. And whereas most plot twists leave us with the pleasing satisfaction of now, finally, perfectly knowing what’s what, these two deliver that deep satisfaction in their big reveals, and then gently tweak the rug one final time, just to remind us not to feel too knowing just yet.

-

When Valora first stepped through the door of my office, the smell of cigarettes followed, along with a palpable physical tension. He was in his thirties but looked older, with a tight, tense frame, deep creases in his face, and bags under his eyes. His thin, sinewy arm muscles twitched under his skin, and his fingers beat a rhythm against each other as he fidgeted to find a comfortable position. He spoke in a staccato voice, interrupting himself when his train of thought outpaced his speech. He had a million questions for us. Who were we? What did we want to know? Where should he start? Did we know about his pending criminal case? He didn’t care if helping us helped him with that; he just didn’t want Dr. Li to get away with fraud or dangerous prescribing.

“Hold on,” we said, Joe and I both reaching toward him, arms outstretched. We had spoken to his attorney to understand the nature of Valora’s arrest and make sure it was okay to meet with him, but, we told him, we couldn’t talk to him about that case without his attorney present.

I pulled out a chair for Valora, picking the most stable one from my collection of discolored brown-upholstered seats in various states of disrepair. I explained that we had received his tip but needed more information to determine whether we could pursue a case. Valora told us his story. We listened, interrupting only to keep him on track; then we went back over every detail from the beginning and opened up countless lines of inquiry. What he told us launched a long and secret investigation, of which only the parts ultimately disclosed at trial ever may be known other than to the judges, attorneys, and prosecutors and, of course, the witnesses and Dr. Li.

At the end of our meeting, Valora repeated that he didn’t care if helping us made a difference in his own case. After his last visit to Dr. Li, he had overdosed on Xanax. He just didn’t want anyone else to get hurt.

“Have you heard about any other overdoses?” Joe asked. It was a key question—one that he would end up asking many times, of many different people. Valora gave Joe just enough to keep him on the road pursuing leads for the next few weeks: a first name, a neighborhood, and a rumor. He also remembered a sign he’d seen in Dr. Li’s office—something about prices per prescription. Sounded too crazy to be true—no doctor would ever do that!

We asked Valora about his health. We had saved these questions until the end. Of course, this was necessary information if we were to understand Valora’s interaction with Dr. Li, but there were other questions in the back of our minds: Was Valora strong enough to go forward? Would it be ethical to expose him to the type of scrutiny and pressure that might be involved in testifying about the case in an eventual trial? As Valora spoke about his illness, Joe and I took in its physical manifestations: foreshortened arm muscles; swollen and stiff hands; body mass reduced to the absolute minimum. Valora had been a body builder, so he was now left with a defined but atrophied body. He’d also struggled with addiction in the past and still denigrated himself for some of the choices he’d made. In body and spirit, he was a man under relentless attack by an unavoidable foe: himself.

Nevertheless, Valora assured us that he was determined to go forward. I explained what this meant: At some point, his identity and testimony would be a matter of public record. Should we ever go to trial, Valora would be cross-examined on the stand by Dr. Li’s defense attorney, including about his criminal record and credibility. We’re far from that now, I explained, and we’ll work with you to prepare if it happens, but it’s not easy. You’ll have to be up-front about all of it. Are you up for it? Yes, he answered. When I shook it, his hand was clammy and cold, but his grip solid.

Afterward, alone in my office, I wondered whether I was up for it—whatever “it” was. Where was this case going? At the time I couldn’t know. Valora’s story raised the possibility of criminal behavior, ranging from prescription sales to health-care fraud, but there also was the possibility that Dr. Li was just a bad physician, running an unprofessional and lax—but not criminal—practice. It would have felt irresponsible to just stop, without a proper resolution or answer, but the uncertainty made me anxious, especially now that Joe, too, was clocking so many hours on the case.

Valora also presented a particular challenge. He was an important fact witness but had vulnerabilities ranging from his criminal record to his health. If I wanted to preserve him as a witness, I’d have to strike a balance between warning him of the difficulties ahead and guiding him through with a steady and neutral hand. It was not my job to protect him—in fact, I had to be level-headed, transparent, and direct about the challenges he would face down the line. And I would have to subject him to the toughest questioning myself.

You would think that this comes naturally to prosecutors. To some, maybe it does. To others, like me, this kind of questioning is an acquired skill and a significant challenge. When you have grown up seeking to avoid conflict at all costs, it takes deliberate effort to speak awkward truths and accept discomfort. That is precisely why I wanted this job: I hoped and expected it would force me to counter my deep-rooted instincts to put everyone at ease and keep every situation conflict-free. Call it voluntary aversion therapy for a lifelong people pleaser. My old way of functioning would be unethical and unprofessional in the context of my work. I had to let it go. It certainly hadn’t served me well in my personal life, either. At tense moments throughout my workdays, as I realized that I was, yet again, trying to appease or avoid tense situations and emotions, scenes flashed through my mind, warning me away from the old trap.

I’d catch myself studying body language for signs of annoyance, frustration, tension, wondering if someone hated me or was angry at me—those fears and feelings then sent me into a spiral of anxiety and paranoia. For too long, I had learned to watch for danger signs, detect the signals, and ward off trouble by any means necessary.

___________________________________

-

Draw a circle. The space inside the circle represents the positive space in the drawing. The negative space would be the shape made by the outside of the circle. It’s most noticeable in cut paper art or silhouettes or even those Nagel prints that were so popular in the 1980s. Positive and Negative Space exists within other forms of art as well: ceramics and sculpture, for example. Since writing is also an artform, the theory of Positive and Negative Space also applies to literature and, specifically in this case, world-building or setting.

Often, readers and new writers assume that world-building is what the author describes in detail—whether that’s the history of the fictional continent, the climate, the system of government, cultures, arts, typical foods, monetary system, and social norms. However, what isn’t said tells a story too. It’s in the clothes the characters wear and the materials they are made from. Wool, for example, means there are sheep or creatures like sheep which in turn means shepherds. The sheep are sheared and that wool is cleaned, carded, spun (either by hand or with a spinning wheel), and either knitted or woven. Next, there’s the color of the cloths. Dyes are made from plants, bugs, and sometimes even animal parts. All of these things must be gathered, processed, and applied. Often, as is the case with indigo, it requires a great deal of water. Lastly, are the clothes in question handmade? Or were they manufactured? In Science Fiction—particularly in Space Opera, there aren’t likely to be fields of cotton or herds of sheep available—particularly if the story is set on a generation star ship or living on the moon. That’s when other technologies, like 3D printers must step in. So much can be implied about a world in a simple castoff sentence about an item of clothing or food.

It might be easier to imagine world-building as an iceberg floating in the sea of plot. The reader only sees a small percentage of it. The rest is deep beneath the water and affects everything in the water—visibly and invisibly. That said, communicating with the empty spaces takes a deft hand because the border between too little and just right is quite thin. In addition, Americans in particular are often socially conditioned to say more and listen less. That’s why world building in the blank spaces is an advanced technique most often employed by authors with experience and skill.

A great deal of worldbuilding can happen with what is left unsaid.

Ray Bradbury, Fahrenheit 451

In Fahrenheit 451, Ray Bradbury does all the things writers are told not to do when it comes to setting. Much of the details are left for the reader to infer for themselves—effectively conveying a powerful sense of isolation and unease. The country in which the story is set isn’t named and neither is the date. Although, one can easily extrapolate that the characters live in some form of futuristic America. The details of the government aren’t filled in, and this heightens the sense that it’s a sinister force. It’s clear that this version of America is at war but why and with whom are also never explained. There seems to be no past—other than a time when books were legal—and no future. There is only the ever present now, now, now. That’s the point. Everything is surface because the characters are forced to live only in the present. Distractions are a way of life. Asking questions is dangerous. And so we learn that this America is ruled by an autocratic government without ever explicitly being told it is. Books aren’t the only things being destroyed. So is the ability to think.

Octavia Butler, Dawn

Octavia Butler also employs negative space in her novel Dawn. The novel opens with the main character trapped in a blank room and no memory of what happened or how she came to be there. The room in question is inside an alien spaceship. Its interior is made up of blank white walls and floors that can be shaped into whatever is needed. However, the power to do so is locked to alien DNA. At some point, the main character, Lilith, must agree to having that DNA implanted in order to operate the doors of her cell. This is, the reader discovers, a major part of the aliens’ culture and existence. In order to survive, they assimilate different parts of various beings as they travel across the universe. They discovered human beings just before they annihilated themselves. The aliens kidnapped/rescued the remaining population with the intent to repopulate the earth. Lilith has been chosen to lead humans on the path to their new future. The blank setting is in place for a large part of the novel until the humans enter an area that has been created to replicate the Amazon rain forest. Other details given to the reader have to do with alien reproduction, intimate relationships, and biology. The entire novel is stark, and its blankness imposes a creepy claustrophobic air.

Iain M. Banks, Culture Series

Iain M. Banks’s “Culture” novels are another great example. Throughout much of the series the reader is directly told very little about The Culture. Most of what is learned is demonstrated through the actions of its agents—themselves largely unreliable narrators. Pretty quickly we’re made aware that The Culture is vast, is run by artificial intelligences with far advanced technology, and considers itself a helpful influence among the lesser technologically inclined species and planets around them. The Culture interferes, but only in ways sanctioned by the main governmental group. At first, the reader might be inclined to believe The Culture is exactly as powerful and beneficent as is claimed, but over time the cumulative buildup of negative consequences begins to erode this view. One is left wondering if the differences in technological and cultural systems are just too enormous for any interactions or attempts at uplift to result in anything but a mixed bag. Ultimately, very little is said about The Culture, but the silence screams more loudly than if pages had been devoted to exposition.

Ursula K. LeGuin, The Left Hand of Darkness

Ursula K. Le Guin’s The Left Hand of Darkness stands out as one of Science Fiction’s greatest works. Genly Ai, a human from Terra, is sent by the Ekumen (a confederation of planets) as an ambassador to the planet Gethen. His objective is to convince the nations of Gethen to join the Ekumen. He starts his journey in the Kingdom of Karhide. Unfortunately, it turns out that Genly Ai knows very little about the beings with whom he’s been sent to negotiate. While the people of Gethen are humanoids, they have key differences in their biology. For a start, they are asexual and possess characteristics of all genders. However, during kemmer (mating season) their bodies transform and they develop sex organs. As a result, their society has certain social strictures surrounding gender. Genly Ai’s maleness creates barriers to communication. Another issue is that while Gethen has similarities to Earth, the world is in the midst of a glaciation period. The Kingdom of Karhide is facing a famine due to the extended winter.

The plot revolves around the relationship between Genly Ai and Estraven the Prime Minister of Karhide. During the course of the book, we’re given information about the planet of Gethen and the customs of multiple cultures native to it. However, readers are left to infer almost all information about Ekumen via the reactions of Genly Ai to the cultures found on Gethen. Not only does this make sense character development-wise—Genly Ai would be more focused on the uniqueness of Gethen’s cultures than he would be on information he already knows and understands—but this juxtaposition also emphasizes the rift between the cultures of Gethen and Ekumen. It makes Ekumen feels more alien than it would if it were expressly described. In addition, Genly Ai’s situation feels more perilous because the reader isn’t clear what else he doesn’t know about the cultures he’s been sent to interact with, building tension in a slow-paced plot.

***

-

https://stephenking.com/works/novel/misery.html

In his own words:

"The inspiration for Misery was a short story by Evelyn Waugh called "The Man Who Loved Dickens." It came to me as I dozed off while on a New York-to-London Concorde flight. Waugh's short story was about a man in South America held prisoner by a chief who falls in love with the stories of Charles Dickens and makes the man read them to him. I wondered what it would be like if Dickens himself was held captive."

This clearly demonstrates a plot line and characters planned in advance and executed according to that plan. MISERY was a huge book and movie deal for King. He now officially joins the club of authors who plot and plan their novels - at least to a certain degree, enough to create a best selling novel. This doesn't mean he didn't vary his approach with other novels, but it contradicts his later claims of never plotting. It's just not true and here is the proof. Realistically though, with a great story concept like this, why not do whatever maximizes the chances of writing a great novel.

-

39 minutes ago, KaraBosshardt said:

I agree with what you say in terms of the context here-long career of being published vs. just starting out, etc. However Stephen King wouldn't be who he is today if he never allowed himself to write the way that he does. If he'd rigidly adhered to the rules of plot structure when he was first starting out then we may not even be talking about him in this post. Take an artist, for example. How do they know which medium works best for them until they allow themselves to try multiple kinds? Any writer cannot truly find their own unique and authentic voice and style of writing until they give themselves the opportunity to try different things.

Perhaps the middle ground here is a semi-loose plot outline that gives you points A, B and C then "pantsing" your way to each? Or, if people are curious but nervous to let their characters lead the way, then perhaps a short story would give them the ability to try it out without having to fully commit. A tasting, if you will.

I guess I should clarify that I'm not pro pantsing, nor am I pro-detailed outlining. I'm pro allowing yourself to try new things.

For writers trying to break in, they need to appease agents and editors reading the work. If they're missing an inciting incident and first major plot point, they're sunk, period. I know that for a fact after 15 years of pitch conference. So the issue becomes, how loose can the plotting be, so to speak, and still get over the line to be fitted for a brass ring? For those self-publishing, it's the wild west. For more literary authors, certainly more flexibility in some cases. For veteran authors with a good readership, also more room to try new things.

As for me, I know my last novel wasn't rigidly following a continuum of points in the same way a screenplay would, however, it didn't veer off into character-inspired tangents. There were tangents, but not spontaneous ones, rather controlled ones that still supported the main story. I wanted to hit that sweet spot between 85,000 to 95,000 and couldn't afford to get crazy. However, one could still spontaneously veer off now and then, but still more or less follow a coherent genre plotting scheme. It makes rising action development much more steady and sure.

It would be curious to do a study of King's early work and later work in the context of plot. However, I believe his scathing comment that linked plotting to bad writers was a deliberate knock and very petty. He didn't have to put it that way even if he did believe plotting to be a bad idea (which I don't believe he does since his novels are not plotless).

In summary, my many years of workshopping and editing have taught me that new writers are better off following the rules of good fiction writing, simply because 99.9% of them flounder in predictable ways--weak story being one of the ways. Later, perhaps, they can experiment.

But hey, if you get published, that's usually a pretty good sign you did something right... course, there are exceptions even to this.

-

___________________________________

The Life and Crimes of Marie Dean Arrington

___________________________________

Marie Dean Arrington had been taking matters into her own hands for her entire life. So when she found herself in a minimum security jail cell—well, what was she supposed to do? Just sit there?

Marie was thirty-five, and she’d been committing crimes for over a decade. At 23, while working at a motel as a maid, making 75 cents an hour for scrubbing floors, she suddenly realized that she could make a lot more money if she just robbed the motel instead. So she robbed her boss, and then she tied herself to a chair. When the police arrived, she said that she was a victim of the robbery. (She might have gotten away with it if it weren’t for her one weaknesses: cigarettes. The police noticed that there were cigarette butts all around the chair, and asked Marie how she managed to smoke since her hands were tied. At that, she confessed.)

Now she was in far more serious trouble. She was facing the electric chair. But she’d been put in a minimum security room in the prison hospital at Florida Correctional Institute for Women at Lowell, even though the man who prosecuted her had protested wildly, saying she was “dangerous and will kill again.” She looked around the room. She got to work.

“It’s like she flew out of here,” said the prison superintendent, the next day.

—

Marie was born in Leesburg, Florida on August 8, 1933. She was Black, and Leesburg was segregated at the time. She dropped out of school in sixth grade. And that’s about all we know of her childhood. Decades later, when she spoke to journalist Gary Corsair about her life, she refused to tell him anything about those early years. Her sister wouldn’t talk about their childhood, either. All Marie ever said about that time in her life was in an interview in 1973, where she declared, “I was never handed anything. Everything I ever got I had to fight like hell for.”

Marie certainly did fight like hell, though she was often fighting on the wrong side of the law. One of her high school classmates remembered her as a “peculiar person” and a “bad seed” who didn’t get very much parental supervision, which led to a lot of drinking and running around with a bad crowd. In her twenties, Marie committed a series of offenses, from petty to serious: forgery at age 22, assault at 23, larceny and robbery at 24, passing bad checks at 28, larceny and vehicle theft at 31. When it came to crime, she wasn’t picky about her victims. She forged her sister’s signature once, to steal money from her bank account, and her sister seemed almost impressed, saying, “Marie can imitate anybody. If she sees yours [your signature] one time, she will imitate yours.”

Most of the people who knew her, it seemed, knew that she wasn’t to be trusted. “No one said anything good about Marie,” her high school classmate remembers. “I knew she really did a lot of little terrible things, bad things, what not, like stealing, drinking, and staying out all time of the night with different guys. But I didn’t have no idea that she would murder anybody. No, I didn’t.”

—

For more about the life and crimes of Marie Dean Arrington, listen to episode 40 of Criminal Broads.

Follow Criminal Broads on Instagram.

-

“Your father was working for the CIA,” said Bogdan, husband of my second cousin, a provocative person, especially after several bottles of local Slovenian wine.

Nine of us were finishing a pleasant dinner in Ribić, a seafood restaurant on the Adriatic coast near Trieste in 2010. We were reminiscing about the years our American and Slovenian families had known each other, a relationship that began in 1951, when I was brought to Yugoslavia as a ten-month-old. My parents were in London for a year on a Fulbright grant when my father decided to visit the Slovenia mountain village his parents left in 1911.

Bogdan’s claim stopped the conversation. “Preposterous, out-of-the-question,” I laughed.

The accusation, unthinkable at the time, stayed with me. I knew the surface details of my father’s life—birthplace, college, Marine Corps, Harvard-educated New School professor—but he was secretive about his private life, and when I was a boy the whole of his work life seemed remote and mysterious. I went off to college, started a career, had my own children, and there was never a good occasion to ask about his early life. My parents divorced in 1969 and his remarriage helped close the window onto his past with my mother. My parent’s lives in their twenties were a sort of pre-history, but with time I discovered new things about them. The secret affairs they kept from me—and from each other.

I remained curious about the Yugoslav trip, but the closest I got were grainy photographs taken during the three-week visit—my parents among smiling relatives in a country recovering from war.

Several years after Bogdan’s allegation, I looked into his claim.

***

My parents—both passed away—never said much about the trip except to recount pleasant stories of being embraced by distant relatives who’d been partisans in the war. There were old photographs of me in the arms of a kindly Slovenian aunt who cared for my brother and me while my parents disappeared for several weeks.

I turned to my father’s memoir, published the year he died. I had skimmed it, but my resentment about the divorce made it difficult for me to read without getting angry at how little he said about the family and how much about himself. He devoted one chapter to the 1951 trip.

The trip was financed by the Voice of America through an old college friend who worked as a propaganda analyst, and wanted a study on Yugoslav reactions to BBC, Radio Moscow, and VOA broadcasts. The VOA was based in New York, but funded and managed from Washington by the State Department. Official support for the trip was rejected by the State Department. George V. Allen, the American ambassador in Belgrade, was concerned that formal sponsorship, if it came to light, would affect fragile relations between the countries. Tito and Stalin had split in 1948, and the US was secretly looking for ways to pull Yugoslavia further from Soviet influence. Frank Wisner, head of the CIA’s covert arm, was secretly negotiating with the UDBA, Yugoslavia’s ministry of state security, to sell military equipment to help Tito resist a Soviet attack.

“I cavalierly agreed to do this study on my own time and at my own risk,” my father wrote. “It did not occur to me that this might be regarded as a form of spying, or that I was an accomplice in Cold War propaganda operations. I was interested in the $500.”

I was startled to read how he thought he’d been engaged in a ‘form of spying.’ I requested a copy of his 115-page VOA report from the archives at The New School where he’d taught sociology for more than 40 years.

My parents’ trip went forward without official State Department clearance, but he was fortunate to get the assistance of the British Foreign Office. They lived at 10 Highgate West Hill in London on the first floor of an old mansion that have been converted to apartments. Peter Carey, their neighbor, befriended my parents, sharing his coal ration during the extremely cold winter of 1950-1951.

Carey, I discovered, was a British military intelligence officer in WWII in Yugoslavia who spoke fluent Serbo-Croatian. He fought in the Balkans 1943-1945, living with partisans, harrying Germans, and interfering with their communications right up to D-Day. When the war ended Carey was temporarily assigned to the British embassy in Belgrade, and then he chose to return to Oxford where he completed a degree in classics. When Carey befriended my father, he was in the British Foreign Office, head of the Yugoslav desk.

Carey readily made himself helpful on the study. He translated Serbo-Croatian transcripts of VOA programs to help my father formulate questions, and he organized personal letters of introduction to high-placed Yugoslavs and British embassy staff. As my father recounts, letters were sent to Zinka Milanov, the world-renowned Croatian opera singer; Lawrence Durrell, the writer, then British Attaché in Belgrade, and a distinguished linguist at the University of Zagreb who was Tito’s English teacher.

The trip started in June 1951. My father wrote: “Readied for the expedition with wife, two babies, and a bicycle, we boarded a train at Waterloo Station headed for Paris for a connection on the Simplon Orient Express to take us to Ljubljana. Even in third class, the accommodations were comfortable until we reached the Yugoslav border at Trieste where we were required to change from French to Yugoslav cars. The Yugoslav train was more like a cattle car outfitted with wooden benches.”

They entered Yugoslavian checkpoint just beyond Trieste, becoming among the first Americans to enter Slovenia by this route since the end of the war. They were interrogated by border guards. Two years earlier, Yugoslavia downed two US Air Force C-47s over Trieste, killing one crew, claiming the American planes had illegally entered Yugoslav air space. But people on the train were cordial to the Americans. My father wrote that old Slovenian peasant women insisted on caring for my brother and me, and my parents were offered bread, wine, and slivovica, the local plum wine. Old and young alike wanted to engage the returning Slovenian in sign-language and broken-English conversations.

My mother was aware of the dangers. Before leaving London, she wrote to a college friend: “Cross your fingers that war doesn’t start while we’re there.”

***

Cold War tensions were at a peak in 1951. The year before, North Korean troops streamed across the 38th Parallel, initiating the Korean War. There was fear in Washington and London that the Soviets would invade Yugoslavia to forcefully reclaim it. The CIA’s National Intelligence Estimate 29, written for Truman in March 1951, concluded there was a “serious possibility the Soviet Union or its satellites, Rumania or Hungary, would invade Yugoslavia.” The British Chiefs of Staff made a similar assessment. Yugoslavia had a long land border with his hostile Communist neighbors and there was concern that Danubian plains north of Belgrade were vulnerable to armored attack.

American intelligence in Yugoslavia was a one-man operation in 1950. The CIA opened its station in Belgrade in 1948 and the first Chief of Station was a junior officer who operated under cover as an interpreter for Ambassador Allen. His principle qualification was that he knew Serbo-Croatian. He operated a translation service with the British embassy, sending Washington whatever intelligence he gleaned from English translations of Tito’s notoriously long speeches and whatever casual intelligence he picked up in bars and restaurants. His job, he explained, was “to go and just soak up Yugoslavia.” But he was one man. The joint translation service with the British assured that whatever went to Washington also went to Peter Carey, head of the Foreign Office Yugoslav desk.

The CIA upgraded its station in January 1951, bringing in Louis Charles Beck, who had been an FBI agent undercover as a US Army captain liaison to Soviet military leadership in Moscow during WWII. He joined the CIA upon its creation in 1948 and came to Belgrade with knowledge of Russian and familiarity with Soviet military thinking. His directive was to “do everything they could to move Tito away from Stalin.”

My parents arrived in Ljubljana at a risky time and they knew the dangers. Yugoslavia’s formidable secret police, the UDBA, had rounded up more than 100,000 Yugoslavs with Soviet sympathies and thousands had died in prison.

My father’s host in Ljubljana was Marjan Sadar, a cousin, and a textile factory manager. My grandparents had generously supported their Yugoslav relatives during the war and my father was embraced with great warmth and affection. He was introduced to uncles, aunts, and cousins, some of whom were look-alikes. Same nose, same blue eyes, same chin. He visited Kropa, the small mountain village his parents had left in 1911, and he was given access to many people who shared stories fighting Germans, and their views of Tito and Stalin.

Sadar secured the use of a state-owned car (one of only a few cars in all of Slovenia), with a driver provided by the Slovenian Communist Party Chief, husband of another cousin. My older brother and I were left in the care of my father’s aunt, Lojzka, and her daughter, while my parents traveled to Ljubljana, Zagreb, Belgrade, and through the countryside. Of course, as a ten-month old, I have no memory of that time. It was only while researching the 1951 trip that I learned Lojzka survived Dachau and her unmarried daughter lived with the stigma of a wartime relationship with a Nazi officer.

My father conducted forty-two interviews, each several hours long, in homes, airport waiting rooms, cafes, farms, and offices—secretly typing up notes at night on a portable Smith Corona. The subject of radio propaganda was of intrinsic interest to Yugoslavs at the time. Yugoslavia was being bombarded with messages from the VOA, BBC, and Radio Moscow and there was little trust in the official news presented by state-controlled Yugoslav radio stations.

He talked with factory workers, party leaders, the old bourgeoisie, famers, plant managers, students, and relatives. His interviews touched on radio listening preferences, but much of his questioning touched on highly sensitive political topics. The 115-page report addressed the consequences of Tito’s break with the USSR, opinions toward America, and gripes about Tito. Taken as a whole, the report is a snapshot assessment of popular opinions toward Cold War adversaries—the United States and the Soviet Union.

He kept his work secret. He wrote: “When doing my interviews, I was unable to take notes for the obvious reason that the study did not officially exist. Keeping a record of the interviews was a problem…I had to remember as much of an interview as possible until I could record it. I kept a visual image of an interview’s setting and memorized key words and phrases in order to reconstruct the account. I recorded my notes whenever I could, usually late night in the privacy of my bedroom. Once recorded, I hid the notes in my baggage.” He thought of himself as an amateur spy, he wrote. And he had a good cover. “No one bothered to probe into the personal affairs of a father traveling with a wife and two children.”

One Slovenia relative wrote to me. “Your parents with chauffeur and interpreter came to Rijeka and left your brother with us (you were in Radovljica alone) and they went down the Dalmatian coast to Split. The story is, your mother was partying with some students and spent a night in the police station. It would be interesting to see what the UDBA archives say about your parents. I am sure they were followed very closely.”

Now, as I think about my parents, both twenty-nine years old at the time, conducting their research and feeling the danger, I do wonder: what were they thinking, leaving their two infant sons in the care of women who were almost strangers, aware the UDBA might be following them. Records of the UDBA, like those of the Stasi, have been made available to the public, and I asked the Slovenia Ministry of Culture to examine its microfiche and papers records for any mention of my parents. I received a reply that all archives were searched and no records were found, followed by a final comment: “The absence of UDBA records indeed seems to be a little surprising in relation to the nature of his work.”

The final 115-page typed report has cross-outs and one page is mysteriously stamped CONFIDENTIAL. The page caught my attention. I had found a copy of the report in my father’s papers in The New School’s archives. The report makes political assessments that would have been of great interest to American intelligence officials who lacked direct knowledge of Yugoslav public opinion. One chapter describes how trusted, word-of-mouth reporting through informal channels occurs along train lines and boats that travel up and down the coast. Another chapter addresses the resentments of the disaffected bourgeoisie, factory workers, and farm laborers toward the Communist Party. The report goes beyond radio listening preferences; it provides a road map for influencing Yugoslav public opinion.

He submitted the final report shortly after returning to the US. He wrote: “To my surprise, within a week I had a call summoning me to Washington for an interview and debriefing with a State Department functionary on the Yugoslav desk.”

My older brother, who interviewed our father at the end of his life, said, “He did go to Washington DC to brief the State Department. That always struck me as an indication that his spying was considered important enough to merit a high-level cross-examination.”

Was my father working for the CIA? Or even MI6? In spite of my father’s claim that he was an ‘amateur spy,’ I am reasonably certain he used the phrase figuratively. The report went to the State Department in Washington and probably also to Carey in London. Given the cozy relationship between the State Department and the CIA in 1951, I suspect the report found its way to the CIA.

I didn’t fully answer the question that I set out to explore, but in the process of looking into Bogdan’s claim I discovered things about my father—his first encounters with relatives with whom he maintained a life-long friendship, curiosity about his roots, the appeal of adventure in a dangerous place, and his willingness to put his family at risk. I thought I knew my father when he was alive. He’s been dead more than a decade, but not a year goes by that I don’t discover something about him that makes me realize that I hardly knew him at all.

*

-

“It is impossible to drive anywhere in America today without encountering a patient, droop-shouldered chap who stands by the roadside and continuously jerks his thumb across his chest. He is the hitch-hiker, one of the strangest products of the auto age, and he is getting to be a prominent part of the American landscape. He is also getting to be an intense pain in the neck. Just why it should be considered proper for a man to stand by the roadside and beg free transportation from total strangers is a mystery….But the hitch-hiker is something more than a nuisance. There are times and places when the hitch-hiker is an actual menace to public safety….[M]urders of motorists by hitch-hikers have been recorded recently in Oregon, Virginia, Nebraska, New Mexico, and Oklahoma….It might also be remembered that when Pretty Boy Floyd was finally hunted down and killed in Ohio he was in the process of hitch-hiking across the country….As an individual, the hitch-hiker may be a likeable chap. As an institution, he is getting to be pretty trying. One wonders just how much longer the American motorist will put up with him.”

—“Hitch-Hiker is Menace and Nuisance,” Santa Rosa Republican (September 11, 1935)

___________________________________

On the afternoon of Monday, February 5, 1940, a handsome, narrow-faced, dark-eyed youth with a mane of black hair calmly walked into the police station at Las Vegas, Nevada, then a small city of some 8500 souls, placed a revolver on a table and quietly implored, “Lock me up. I’ve just killed a man.” Asked to explain himself, he added “I guess I’m just a smart hitchhiker. I killed him to get some money.” Upon examining the car which the darkly attractive young man had driven into the city, the police found blood spattered over the seat and floorboards and an empty gun cartridge on the floor. The self-described “smart hitchhiker,” who gave his name as George Emanuel, his native state as Indiana and his age as twenty-three, guided police some thirty miles southwest of Las Vegas, to the turnoff to the small town of Goodsprings. There by the side of the road the police found the body of a man who bore a fatal gunshot wound to the head and whose clothes had been riffled, presumably for cash.

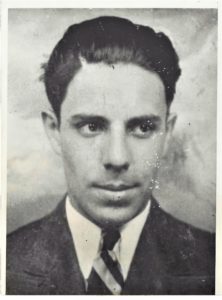

George Emanuel

George Emanuel

Earlier that day the murdered man, stocky, forty-two year old Floyd Monroe Brumbaugh, had picked up the hitchhiking George Emanuel in the town of Barstow, California, offering to take him to Las Vegas. According to George’s account, the two men had ridden peaceably from Barstow across the California-Nevada state line, “talking of this and that,” until, some thirty miles from Las Vegas, the younger man suddenly pulled a gun from his pocket and shot his benefactor point blank in the head, killing him instantly. “He never saw it coming,” George told the police. “He was looking straight ahead and never knew what hit him.” Brumbaugh, who had been driving at around fifty-five miles per hour when George fired the fatal shot, slumped down over the steering wheel, causing the car to swerve, but his frantic murderer was able to shove his bloody, brain-spattered corpse aside and gain control of the careening machine. After taking the turnoff to Goodsprings, George pulled over and dumped Brumbaugh’s body out by the side of the road, going through his pockets for cash and finding but a single penny. (In his haste he missed the $6.50—about $118 dollars today—which Brumbaugh had carried on his person.) Demoralized, George dazedly drove into Las Vegas, where he gave himself up to local authorities, insisting that robbery had been his sole motive for the shocking slaying. Soon sensation-hungry newspapers across the country were emblazoning news of Nevada’s ironic “one-cent hitchhiker slaying,” doubtlessly spurred on by the murderer’s dark good looks and spotless social standing.

A pulchritudinous scion of highly respectable small-town, white-bread Middle America, George Hawley Emanuel claimed among his distinguished forebears not only a prominent Indiana doctor and lawyer but his beloved paternal grandmother, Ida Virginia Emanuel, head librarian of Auburn, Indiana’s Eckhart Public Library until her death in 1923. George’s identically named late father, who died when young George was only sixteen, had been a Chicago journalist and publicity agent while his widowed mother, Irene, was employed as the executive secretary to the Family Welfare Association of Evansville, Indiana—the Emanuel family, which also included George’s younger brother and sister, John and Mary, having moved from Chicago to Evansville four years earlier.

Young George had graduated with honors from Evansville High School and attended Howell Military Academy when he married welfare worker Marjorie McKinnon, relocating with her to Indianapolis. The couple divorced in 1939 and a despondent George returned home to live with his mother, clerking in a bookstore and working around the house until October, when he resolved, like many another restless soul during the unsettled years of the Depression, to hitch his way to the Golden State of California. His avowed plan was to visit his brother John, a student at Stanford University, and a couple of aunts. Once in California he became a laborer with the North American Airplane Factory in Inglewood, near Los Angeles, where the advent of the Second World War had already started a boom in the munitions industry. However, during the first weekend of February 1940 George, having abruptly quit his factory job, started drinking heavily and lost a large sum of money at the racetrack at Santa Anita Park in the city of Arcadia. On Sunday he determined to pick up such meagre stakes as he had in the Golden State and hitchhike to New Orleans, first purloining and loading the gun owned by one of his roommates. In Los Angles a friendly man picked him up in his car and carried him some eighty miles, dropping him off near Victorville, where another obliging fellow spotted him and drove him an additional forty miles to Barstow, cite of his fatal encounter with Floyd Brumbaugh.

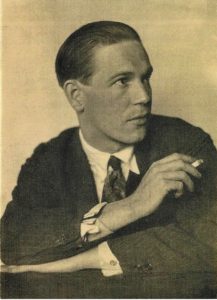

Floyd Brumbaugh and Willie Bell Brumbraugh

Floyd Brumbaugh and Willie Bell Brumbraugh