Each month the CrimeReads editors make their selections for the best upcoming fiction in crime, mystery, and thrillers.

*

These are the things that you at home need not even try to understand.

—Ernie Pyle, war correspondent

Between the abduction and cannibal-mutilation murder of Grace Budd by Albert Fish in 1928 and the unsolved murder of Elizabeth Short, “the Black Dahlia,” in 1947, a generation of future “epidemic era” serial killers was born, including Juan Corona (1934), Angelo Buono (1934), Charles Manson(1934), Joseph Kallinger (1935), Henry Lee Lucas (1936), Carroll Edward Cole (1938), Jerry Brudos (1939), Dean Corll (1939), Patrick Kearney (1939), Robert Hansen (1939), Lawrence Bittaker (1940), John Wayne Gacy (1942), Rodney Alcala (1943), Gary Heidnik (1943), Arthur Shawcross (1945), Dennis Rader (1945), Robert Rhoades (1945), Chris Wilder (1945), Randy Kraft (1945), Manuel Moore (1945), Paul Knowles (1946), Ted Bundy (1946), Richard Cottingham (1946), Gerald Gallego (1946), Gerard Schaefer (1946), William Bonin (1947), Ottis Toole (1947), John N. Collins (1947), Herbert Baumeister (1947) and Herbert Mullin (1947).

They were followed by the births of Edmund Kemper (1948), Douglas Clark (1948), Gary Ridgway (1949), Robert Berdella (1949), Richard Chase (1950), William Suff (1950), Randy Woodfield (1950), Joseph Franklin (1950), Gerald Stano (1951), Kenneth Bianchi (1951), Gary Schaefer (1951), Robert Yates (1952), David Berkowitz (1953), Carl Eugene Watts (1953), Robin Gecht (1953), David Gore (1953), Bobby Joe Long (1953), Danny Rolling (1954), Keith Jesperson (1955), Alton Coleman (1955), Wayne Williams (1958), Joel Rifkin (1959), Anthony Sowell (1959), Richard Ramirez (1960), Charles Ng (1960) and Jeffrey Dahmer (1960).

The vast majority of these children would not begin their serial killing until they were in their late twenties or early thirties in the 1970s and 1980s, with the exception of Edmund Kemper, who first killed in 1964, Patrick Kearney who began killing in 1965, John N. Collins in 1967, Richard Cottingham in 1967 (perhaps even as early as 1963) and Jerry Brudos in 1968.

In trying to explain the surge of serial murders from the 1970s to the 1990s, we often invoke the epoch in which the serial killings happened. From the cultural and sexual revolutions of the 1960s and the wanton hedonism of the 1970s to the cruel Reaganomics callousness of the 1980s and the rapacious greed of the 1990s, we argued that somehow serial killing was a product of the violent times in which the killing happened. But that was only half the story.

Psychopathology is first shaped in childhood, so to understand surge-era serial killers of the 1970s and 1980s, we actually need to look back some twenty or thirty years earlier, to the eras in which they were steeped as children in the 1940s and 1950s. I’ve already described the process of basic “scripting” of transgressive fantasies. The direction these “scripts” take and how people are chosen for the role of victim in them has a complex structure pinning it all together.

***

In explaining surges of serial murder, criminologist Steven Egger argues, it was not that there were more serial killers but that there were more available victims whose worth was discounted and devalued by society. Egger maintains that society perceives certain categories of murder victims as “less-dead” than others, such as sex workers, homeless transients, drug addicts, the mentally ill, runaway youths, senior citizens, minorities, Indigenous women and the inner-city poor; these victims are all perceived as less-dead than, say, a white college girl from a middle-class suburb or an innocent fair-haired child. Sometimes the disappearance of these victims is not even reported. Criminologists label them the “missing missing.”

Egger writes:

“The victims of serial killers, viewed when alive as a devalued strata of humanity, become ‘less-dead’ (since for many they were less-alive before their death and now they become the ‘never-were’) and their demise becomes the elimination of sores or blemishes cleansed by those who dare to wash away these undesirable elements.”

We popularly regard serial killers as disconnected outcasts, as those who reject societal norms, but more often the opposite is true. In killing prostitutes, Jack the Ripper, for example, was targeting the women that Victorian society chose for its most vehement disdain and scorn. Gary Ridgway, “the Green River Killer,” who was convicted for the murder of forty-nine women, mostly sex workers, said he thought he was doing the police a favor, because they themselves could not deal with the problem of prostitution. As Angus McLaren observed in his study of Victorian-era serial killer Dr. Thomas Neill Cream, who murdered at least five victims (prostitutes and unmarried women coming to him seeking abortions), Cream’s murders “were determined largely by the society that produced them.”

The serial killer, according to McLaren, rather than being an outcast, is “likely best understood not so much as an ‘outlaw’ as an ‘oversocialized’ individual who saw himself simply carrying out sentences that society at large leveled.” Social critic Mark Seltzer suggests that serial killers today are fed and nurtured by a “wound culture,” “the public fascination with torn and open bodies and opened persons, a collective gathering around shock, trauma, and the wound,” to which serial killers respond with their own homicidal contributions in a process that Seltzer calls “mimetic compulsion.”

Or, as the late Robert Kennedy once put it more simply, “Every society gets the kind of criminal it deserves.”

***

Prior to the First World War (1914–1918), American society was relatively disciplined and cohesively structured between the upper, middle and working classes, between rural and urban, and between white and people of color. The privileges and burdens, the rights and responsibilities of each class of Americans, aside from that of industrial labor, were rarely challenged, questioned or crossed before the Great War. In the way that medieval Europeans with passive Christian forbearance lived their place in society from birth to death as divine destiny, Americans settled into their place in the social hierarchy on the basis of Horatio Alger’s “rags-to-riches” promise that with hard work and prayer, anyone can rise in the American class hierarchy to something spectacularly better than what they were born into. Most Americans quietly settled for moderately better, and did so, and that was what made America great.

World War I and its aftermath changed all that. It challenged the notion that duty and sacrifice would be rewarded with real change. A “Lost Generation” of disillusioned and shell-shocked American men returned from the horrors of a “war to end all wars” that did nothing of the sort.

In October 1929, it all crashed on Wall Street, wiping out billions of dollars of wealth in what became known as the Great Depression. By 1933, the unemployment rate in the United States was an astonishing 25 percent. Making matters worse in the Midwest, an environmental disaster in the form of the Dust Bowl uprooted millions of families from their homes and farms. All this without a “social safety net” of welfare, food stamps or public housing. Men raised and socialized for generations into their role as family patriarchs and breadwinners suddenly found themselves helpless and broken, shivering in a soup kitchen line just to eat.

***

That battered generation of young men who matured over the 1930s was now sent into what was going to be history’s most lethal and brutal war, sometimes referred to as the “last good war” because of the unambiguous evil of the enemy we fought.

In December 1941, Japan bombed Pearl Harbor and Nazi Germany declared war on the United States, dragging it into World War II. Some 16.5 million men (61 percent of American males between the ages of eighteen and thirty-six) were mobilized into the military and deployed in Europe, the Pacific or on wartime duty at home. Their average age was twenty-six.

About 990,000 of them would see combat, and 405,000 were killed. Nothing in their experience at home prepared them for what they were going to see in this war, a primitive war of total kill-or-be-killed annihilation culminating with two thermonuclear detonations that in several nanoseconds incinerated 120,000 men, women and children. Winston Churchill said it best: “The latest refinements of science are linked with the cruelties of the Stone Age.”

***

The familiar term PTSD—post-traumatic stress disorder—would appear only the 1980s in the wake of the Vietnam War, but during World War II the terms “combat stress reaction” (CSR), “battle fatigue” or “battle neurosis” were rolled up into a general statistical term: “neuropsychiatric casualty.” Of American ground combat troops deployed in World War II, an astonishing 37 percent were discharged and sent home as neuropsychiatric casualties. It just wasn’t often reported or talked about. America preferred to see their sons coming home less a leg or arm than “crazy in the head.” Hometown newspapers would euphemistically report on returning “wounded” or “casualty” figures without specifying the nature of the “wound” or “casualty.”

Returning World War II veterans did not have the current diagnosis of PTSD to take comfort in. “Combat psychoneurosis” sounded shamefully “psycho,” and most wanted to just go home and forget about everything they had seen and endured. Our returning soldiers were patted on the back and told they did their duty in a just cause, were given medals and a parade and tossed a GI Bill and then sent home to suck it up in sullen silence in the privacy of their own trauma. They couldn’t even talk to their families about it. Nobody wanted to hear it . . . at least not the truth. Our traumatized fathers and grandfathers were forever trapped in silence, like prehistoric life preserved in transparent amber as “the greatest generation any society has ever produced,” a term journalist Tom Brokaw coined in his 1998 book, The Greatest Generation.

***

It wasn’t just the war over there that affected people. There was a seismic shift in popular culture at home that took a darker and more paranoid turn. In his disturbing study of postwar America, The Noir Forties: The American People from Victory to Cold War, historian Richard Lingeman describes an era of anxiety and dread rather than the optimistic Norman Rockwell impression that we have of happy-to-be-home soldiers and optimistic baby-boom years. After describing the mass arrivals in 1947 of hundreds of thousands of coffins from Europe and the Pacific (the war dead had been temporarily interred overseas, and families had the option to leave them there in military cemeteries or have them shipped home for reburial), Lingemen describes how Hollywood launched a new genre of brutally violent and cynical crime movies, the so-called red meat movies that French film critics would later dub “film noir.” Lingemen writes that the typical film noir was “peopled with recognizable contemporary American types who spoke of death in callous, calculating language and shot with dark chiaroscuro lighting, told an unedifying tabloid-style story of greed, lust, and murder. . . .”

It wasn’t just the war over there that affected people. There was a seismic shift in popular culture at home that took a darker and more paranoid turn.It was something the New York Times pondered in the last days of the war, describing a crop of “homicidal films” either just released or in production, like Double Indemnity, Murder, My Sweet, Conflict, Laura, The Postman Always Rings Twice, The Lady in the Lake, Blue Dahlia, Serenade and The Big Sleep.

Hollywood says the moviegoer is getting this type of story because he likes it, and psychologists explain that he likes because it serves as a violent escape in tune with the violence of the times, a cathartic for pent-up emotions. . . . The average moviegoer has become calloused to death, hardened to homicide and more capable of understanding a murderer’s motive. After watching a newsreel showing the horrors of a German concentration camp, the movie fan, they say, feels no shock, no remorse, no moral repugnance when the screen villain puts a bullet through his wife’s head or shoves her off a cliff and runs away with his voluptuous next-door neighbor.

The femme fatale was now raised to iconic heights, starring in the film noir as a greedy, narcissistic, bored, oversexed female often plotting to do away with her poor husband. An article in the New York Times in 1946 entitled “The American Woman? Not for This GI” gave voice to the thousands of frustrated veterans coming home to find women transformed:

Being nice is almost a lost art among American women. They elbow their way through crowds, swipe your seat at bars and bump and push their way around regardless. Their idea of equality is to enjoy all the rights men are supposed to have with none of the responsibilities. . . . The business amazon would not fit into the feminine pattern in France or Italy. . . . They are mainly interested in the rather fundamental business of getting married, having children and making the best homes their means or condition will allow. They feel that they can best attain their goals by being easy on the eyes and nerves of their menfolk. . . . Despite the terrible beating many women in Europe have taken, I heard few complaints from them and rarely met one, either young or old, whose courtesy and desire to please left anything wanting.

***

Cave drawings, myths, popular lore, folk and fairy tales, fables and literature often reflect the hidden unspoken yearnings and deep, dark fears and hates in a society, as well as its traumas and triumphs. In the limited three-TV-channel-plus-Hollywood-movies world of postwar American popular culture, without cable and satellite TV, without video, without video games, DVDs, the Internet or Netflix, guys read mainstream magazines, comics and paperbacks for entertainment. Other than movies, radio and later TV, there wasn’t much of anything else in the way of popular narrative entertainment.

What entertained and came to obsess some boys of Ted Bundy’s and John Wayne Gacy’s generation, and their fathers, were dozens of men’s adventure magazines like Argosy, Saga, True, Stag, Male, Man’s Adventure, True Adventure, Man’s Action and True Men.

From the 1940s to the 1970s, these magazines often presented salaciously exaggerated accounts of wartime Nazi rape atrocities. The magazine covers featured garish images of bound and battered women with headlines like SOFT NUDES FOR THE NAZIS’ DOKTOR HORROR; HITLER’S HIDEOUS HAREM OF AGONY; GRISLY RITES OF HITLER’S MONSTER FLESH STRIPPER; HOW THE NAZIS FED TANYA SEX DRUGS; CRYPT IN HELL FOR HITLER’S PASSION SLAVES.

Even today, nearly seventy years after the war, the Nazis and their psychosexual sadistic cruelty remain a major theme in our popular culture and imagination, from Ilsa, She Wolf of the SS, The Night Porter and Seven Beauties to the more recent Inglourious Basterds and The Reader.

The adventure magazines were known as the “sweats” for the luridly colored cover illustrations of male torturers and female victims glistening with sweat, an effect enhanced by casein paints and acrylics used by the cover artists. These magazines featured not only a gamut of Nazi and Japanese atrocities but sweaty cannibal stories based in the South Seas and Africa; Middle East harem rape scenarios; and eventually Cold War, Korean War and Vietnam War vice and torture themes.

Parallel to the “sweats” was a genre of grotesque crime tabloids like the National Enquirer (before it turned to celebrity gossip) and titles like Midnight, Exploiter, Globe, Flash and Examiner and true-detective magazines that mixed staged bondage photos with horrific crime scene photos and tales of sex, death and mutilation, with headlines like 39 STAB WOUNDS WAS ALL THE NAKED STRIPPER WORE; HE KILLED HER MOTHER AND THEN FORCED HER TO COMMIT UNNATURAL SEX ACTS; I LIKE TO SEE NUDE WOMEN LYING IN BLOOD; SEX MONSTERS! THE SLUT HITCHHIKER’S LAST RIDE TO DOOM; RAPE ME BUT DON’T KILL ME.

All these hundreds of magazines had one thing in common: their covers featured a photograph of a professional model posing as a bound victim (detective magazines) or a lurid painted illustration of a bound victim (men’s adventure magazines). Either way, she was inevitably scantily clad or her dress was in disarray or tatters, her skirt hiked up to expose her thighs or stockings, her breasts straining under the thin material of her torn clothing, her bronzed flesh glowing with a fine sheen of perspiration, often with bound legs or legs spread open, tied up in a torture chamber, in a basement, on the floor, on a bed, on the ground outside; tied to a chair, a table, a rack, a sacrificial pole; in a cage or suspended from a dungeon ceiling next to red-hot pokers and branding irons heating on glowing coals, turning on a roasting spit to be cooked by lusty cannibals, strapped spread-eagle on surgical tables for mad Nazi scientists to probe and mutilate. The woman’s face is contorted in fear and submission, sometimes gazing out from the magazine cover toward the male reader, as if she was the reader’s victim, his personal slave who could be possessed for the price of the magazine.

Norm Eastman, one of the cover artists for those magazines in the 1950s, recalled in 2003, “I often wondered why they stuck with the torture themes so much. That must have been where they were heavy with sales. I really was kind of ashamed of painting them, though I am not sure they did any harm. It did seem like a weird thing to do.”

Women in these blatantly misogynistic publications were portrayed in only two biblically paraphilic ways: either as captives bound and forced into sex against their will or as sexually aggressive, bare-shouldered women with a cigarette dangling from their lips, subject to punishment or death for their evil-minded sexuality. In this paraphilic world of the “sweats,” women were either a sacred Madonna defiled or a profligate whore punished; there were no other options available.

These magazines were not squirreled away behind counters or in adult bookstores or limited to some subculture; they were as mainstream as apple pie. Some had monthly circulations of over two million copies at their height and were openly sold everywhere: on newsstands; in grocery stores, candy stores, supermarkets; on drugstore magazine racks, right next to Time, Life, National Geographic, Popular Mechanics and Ladies’ Home Journal. They would be found lying around anywhere and everywhere men and their sons gathered, in workshops, barbershops, auto shop waiting rooms, mail rooms, locker rooms and factory lunchrooms. At their peak, there were over a hundred monthly adventure and true-detective magazine titles, available to all ages.

All this in a country where it is still taboo to show even a glimpse of a bare female breast or buttock on television.

These men’s magazines, along with true-detective magazines, would increasingly be cited as favorite childhood and adolescent reading by “golden age” serial killers.

__________________________________

I’ve always loved, and been comforted by, television, but I have found myself turning to it more and more, as I’m sure many of you have, during the past year. Nothing can make the stresses, exhaustions, or sadnesses of the pandemic go away for good, but television *can* make the days move faster, which is all that we can ask for. Escapism. That’s what I want. Well, actually, what I really want is for my brilliant mother and her amazing close friend (love you, Aunt Chris!) to write and star in a show about two super clever, beautiful, sixty-ish-year-old women who run a PI business together. But if that can’t happen, I want to watch something similar.

See, lately, I’ve found that my appetite for television has narrowed. Normally, in my downtime, when I’m trying to relax, I like genial, erudite sitcoms of any decade, lighthearted or comical mysteries with no traumatizing imagery, shows where smart con artists fleece the rich for the good of humankind, and anything involving Baby Yoda. Nothing upsetting. No serial killers. No sex crime. No violence against women. No true crime. No abductions or torture. You get the picture.

But recently, I’ve been craving something even more specific: I only want to watch clever mysteries with high production value and women-heavy casts. Maybe it’s just because everything else is demoralizing that I have no interest whatsoever in watching “genius” male detectives do their thing, since this is tedious enough during normal life and I have no patience left. But, by and large, even more than usual, I find myself wanting specifically to watch genius women detectives. To be clear, I don’t want to watch just anything in this genre just because it features women (there is plenty of crap out there pretending to be feminist for its prominent featuring of women… Ocean’s 8 cough cough). And I don’t want the show to use “feminism” to gloss over or excuse various atrocities perpetrated or problematic policies, either. Here, I should clarify that I don’t want to watch genius women “cops.” i just want to watch someone who looks remotely like me waltz into a crime scene in a really nice coat, inspect a few items on the floor, and go on to solve a puzzle with alacrity and dexterity that surpasses everyone else in the vicinity, especially the police. I should add that corporate feminism makes me cringe, so I’m not trying to hit you over the head with the vibes from the “strong female lead” Netflix category from a few years back. This isn’t some “you go girl”-tinted scheme to get you to buy or click on stuff. I just want to watch cool women being cool, OKAY?

So, what are the parameters? First off, no men. Or, really few men. I really, really don’t want to watch a genius male detective have a female sidekick, even if she’s smart or the casting is vanguard (my apologies, Dr. Joan Watson). Now, the woman detective in the show I watch can have a male sidekick, but I’d prefer if the partner were a woman. I want to watch someone whose successes mean something extra-personal to me. Second, these are fun shows, not super-dark or terrifying shows. No Happy Valley or SVU. The goal here is to be able to sleep at night. (Ideally, in the gorgeous patterned pajamas Yûko Takeuchi wears in Miss Sherlock, but we can’t have it all. I checked. They’re sold out.)

I ranked them on a scale, not in terms of quality, but from HARDCORE to COZY, to help you pick a winning series. The list should feel increasingly soporific as you scroll down.

Veronica Mars

Am I actually putting Veronica Mars, a show everyone knows about, on this list? Yes, just in case. This gritty but fun neo-noir series (just renewed, many years later!) about a teenage outcast (Kristen Bell) solving the murder of her best friend (Amanda Seyfried), and helping out her PI father (Enrico Colantoni), is definitely one you should have under your belt.

(Available to stream on Hulu)

Riviera

You know what’s pretty enjoyable? Riviera. In which the universally-beloved Julia Stiles stars as Georgina a wealthy, newly-married art-curator who discovers after her billionaire husband is killed (his yacht explodes!) that his entire financial empire was built on really shady stuff. Our EIC Dwyer Murphy has been recommending it for months, and I decided to give it a whirl. As expected, Julia Stiles decides to figure out what this is all about, partly for her self, partly to protect their family. Sometimes it can get fairly rote, but the aesthetic is so compelling, I almost don’t care. (The setting is “glitzy European waterfronts,” if you haven’t guessed.) Normally, I really don’t love shows about rich people being rich, but I miss Europe. Plus, I do really like splashy, big budget shows full of intrigue and competent, resourceful amateur sleuths.

(Available to stream on YouTube TV)

The Flight Attendant

I had a LOT fun watching The Flight Attendant, HBO’s high-flying new series based on the novel by Chris Bohjalian). Cassie (Kaley Cuoco) is an alcoholic, carousing flight-attendant who, after one date with a handsome traveler, wakes up in a trendy Bangkock hotel room next to his (very) dead body. Terrified she’ll be blamed for the crime, she decides to wings her own amateur investigation into what really happened. Zosia Mamet plays her concerned lawyer best friend with the utmost realness. My favorite appearance is by Scottish character actress Michelle Gomez, whose face I have frequently called “a carnival of sarcasm.” She is a mysterious assassin hot on Cassie’s trail as she walks unknowingly into dangerous international intrigue.

(Available to stream on HBO Max)

Stumptown

Although Stumptown, the rainy adaptation of Greg Rucka and Matthew Southworth’s comic book series of the same name, is NEITHER cozy, nor precisely lighthearted, I’m sticking it on here because it’s a focused, non-traumatizing story about a strong woman who chips away at local corruption and greed, using her PI license and some light body combat. Dex Perios (Cobue Smulders) is a wry ex-marine with a broken heart and a drinking problem who winds up becoming a PI in Portland. I like how this show emphasizes the actual process of acquiring one’s PI credentials, as well as Dex’s closet of VERY nice coats. Plus, as I’ve said before, it productively represents its disabled characters, and features Native actors in complex, weighty roles.

(Available to stream on Hulu)

Miss Sherlock

My favorite series as of late, HBO Asia’s sleek Miss Sherlock, is one of the best Holmesian adaptations I’ve ever seen. This modern, female, Japanese reboot borrows just enough from its source material to inspire a totally new story. And it’s great fun. Dr. Wato Tachibana (who, with her honorific title, is called “Wato-san,” which is amazing) returns to Tokyo from medical volunteer work in Syria to witness the strange murder of her mentor, a traumatic event which leads her to meet a strange consulting detective, a mysterious, elegant woman who goes by the name “Sherlock” and who has tremendous powers of observation (Yûko Takeuchi). They wind up collaborating on the case, and ultimately living together. But this isn’t the chummy partnership of Holmes-and-Watson you’ve come to know; more than simply being motivated to solve crimes by boredom, this Sherlock is motivated solely by her own pleasure. A bossy, self-directed, antisocial, cranky, often whiny genius, Takeuchi’s Sherlock loves dressing up in expensive, funky clothes to sit in her apartment all day, just as much as she loves cracking impossible puzzles (and grins with excitement whenever the plot thickens). She’s even a little mean to Wato (Shihori Kanjiya), who, on the other hand, is shy, sympathetic, and sensitive—dealing with her own demons, PTSD that has begun to rage since her return to Japan. Their friendship becomes more like a sisterhood—fraught, frustrated, turbulent, triumphant.

(Available to stream on HBO Max)

Year of the Rabbit

The boisterous series Year of the Rabbit has more men in its core crime-solving team than is ideal for this list, but Susan Wokoma’s Mabel is such a good detective, and the surrounding men are wholly daffy that it’s clear they’re not taking away her spotlight. Mabel is a Black female detective living in London during the Victorian era. She has the skills, and the connections (she’s the Police Chief’s adopted daughter), but she still has countless odds stacked against her, when it comes to getting the appropriate credit and compensation for what she’s capable of. Still, Mabel is undaunted.

(Watch on Amazon with Topic)

Vera

The phenomenally talented Brenda Blethyn shines in Vera, a detective show set in Northumberland, about a crotchety, sarcastic, messy, but brilliant female DCI named Vera Stanhope. We’ve seen the archetype plenty of times, but not enough in female characters. And Blethyn is so good, she makes the whole thing feel brand-new. This is the only show with a cop at its helm, and I’m making the exception because Vera is so condescending towards the police, it’s a wonder why she isn’t a PI.

(Available to stream on Acorn and Amazon Prime, with Acorn)

Teenage Bounty Hunters

I’ll never stop championing Teenage Bounty Hunters, which is both amazing and tragically cancelled. Created by Kathleen Jordan, this critically-beloved sleeper hit is the story of 16-year-old twin sisters Blair and Sterling (Anjelica Bette Fellini and Maddie Phillips) who begin an after-school side-hustle working for a middle-aged bounty hunter (Kadeem Hardison) who maybe can’t run as fast as he used to. Blair is super fast and Sterling is an ace with a gun. But between chasing bad guys and high-school problems, they find a lot of difficult stuff to deal with. Set in the affluent Atlanta suburbs, this is a smart, sincere show that is just as also in asking questions about who profits from arrests, and prison, in general. Which it is able to do *very* effectively for its setting in the deep South, real Trump territory. The show has a lot to say about race, class, and sexuality, particularly whiteness (and Southern white womanhood). But it’s also just an endearing romp. Maybe there’s too much high school-related self-discovery and drama than “mystery-solving,” PER SE, for it to be on this list, but you should overlook this. You’ll thank me later.

(Available to stream on Netflix)

The Mrs. Bradley Mysteries

There are only five episodes of The Mrs. Bradley Mysteries, which is a SHAME, because they are eminently delightful. The legendary Diana Rigg plays the wealthy, meddlesome, brassy Mrs. Bradley, a passionate suffragette who suffers no fools, and loves to solve crimes. Again, there are too few episodes (WHY!?), but they will charm and entertain you. And few actors can spellbind an audience quite like Rigg.

(Available to stream on Amazon Prime and Britbox)

Miss Fisher’s Murder Mysteries (Netflix)

The grand-dame of all female-led murder mystery shows has to be the Roaring-20s-set Miss Fisher’s Murder Mysteries, about a very game, cunning flapper named Phyrne Fisher (Essie Davis) who has just inherited a vast fortune and lives in an enormous house in Melbourne. She lives with a crew of skilled factotums, and loves to solve mysteries, to the consternation (and eventual fascination) of the local police chief. There’s a mysterious amount of really fake-looking CGI, and sometimes the fabulous costumes look a biiiiiit too “costume-party” than totally believable, but it’s hard not to love watching a very confident woman doing whatever she wants. Also, a high point is that Phryne’s best friend is an out-lesbian doctor, who wears pants! I WISH 20s America could handle stuff like that. This show is delightful to the very last drop. (Be warned, the show tries to be all dark in Season 1 by weaving in a plot about Phyrne’s sister being kidnapped and murdered as a child. It is upsetting. But once this arc is over, the series settles into something vastly more relaxing).

(Available to stream on Acorn and Amazon Prime, with Acorn)

Murder, She Wrote

Don’t forget the great-grand dame all female-led murder mystery shows, which needs no introduction on this website.

(Stream on Philo, whatever that is)

Death Comes to Pemberly

Elizabeth Bennett is our detective protagonist in Death Comes to Pemberly, based on the adaptation of P.D. James’s late-career fanfiction of the same name. Elizabeth and Darcy have been married for a few years and all is blissful at Pemberly until the original novel’s entire cast shows up… and then there is a murder!

(Available to stream on Netflix)

Frankie Drake Mysteries

I haven’t watched much of the Frankie Drake Mysteries, but they seem very soothing, in a Miss Fisher kind of way. Frankie Drake (Lauren Lee Smith) is a pants-wearing Private Eye who opens an office in 1920s Toronto with an aim of helping the downtrodden. She and her glamorous partner Trudy Clarke (Chantel Riley) remain undaunted by even the most treacherous-seeming of circumstances. Plus they have help in their crime-solving from Flo (Sharon Matthews) at the morgue, and Mary (Rebecca Liddard) at the police station. I find myself being not-totally-convinced by the aesthetic (it looks a BUNCH more like a costume party than Miss Fisher does) but it’s a nice time if you want to flop on your couch and watch women supporting one another, especially at a historical moment crucial in the history of women’s social and political advancement.

(Available to stream on Amazon Prime and Thirteen Passport)

Agatha Raisin

Agatha Raisin is so quirky and cute and full of sneaking around and meddling. It’s fresh and perky without being cloying. Agatha Raisin (the brilliantly-talented Ashley Jensen) is a PR consultant-turned-amateur detectives who solves murders in the Cotswolds. TELEVISION SUNSHINE, I TELL YOU.

(Available to stream on Acorn and Amazon Prime, with Acorn)

Marple

There are LOTS of adaptations of Agatha Christie’s Miss Marple stories, and I recommend all of them. But right now, I’m going to recommend this recent adaptation, which stars both Geraldine McEwan and Julia McKenzie starred in the title role. (Nothing too formally funky… McEwan was cast from 2004 to 2007, and McKenzie from 2008 to 2013). If you like watching women-who-are-underestimated-for-their-gender-and-age turn out to get the better of everyone, LOOK NO FURTHER.

(Available to stream on Acorn and Amazon Prime, with Acorn)

Rosemary & Thyme

This show is especially soothing for its preponderance of beautiful foliage. Rosemary Boxer and Laura Thyme are just two professional gardeners who wind up feeling a bit bereft and alone: Rosemary is newly single after her husband leaves her for another woman, while Laura is laid off from her job as a university lecturer specializing in horticulture. But it’s fine, because they have each other, and a burgeoning hobby for solving crimes. There’s nothing like investigating a murder to put the rose back in one’s cheeks.

(Available to stream on BritBox, or Amazon)

Some people are great at movie trivia. Some know all the U.S. state capitals. Me? I’m a walking encyclopedia of famous authors who have committed crimes. (Yes, I’m as much fun at parties as I sound. Invite me, post-COVID.)

This niche interest started when I began reading about the sixteenth-century English poet Christopher “Kit” Marlowe for a college literature class. Usually, the bios of classic British authors are pretty easy to skim: went to Oxford and/or Cambridge, moved to London, published some writing, racked up debts, died eventually. Now, to be fair, all of these facts are also true for Marlowe. But that’s leaving out the good parts.

There’s the 1589 arrest for murder. The dramatic seven-year career in international espionage. The 1592 arrest for counterfeiting money. The other 1592 arrest, that one for brawling. The 1593 arrest for atheism. The threatened 1593 arrest for sedition, which only didn’t happen because Marlowe was stabbed first.

As a longtime fan of crime fiction and historical crime fiction in particular, Kit’s biography was like catnip for me. I went deep down the research rabbit hole and never looked back. One result of this research is my first novel, A Tip for the Hangman. The book takes the covert and criminal activities in Marlowe’s life and reshapes them as a spy thriller, complete with secret codes and international missions. I hope it’s as much fun for others to read as it was for me to write, because I had a blast.

The other result? Tell me that a canonized author committed a weird crime, and you have my complete and undivided attention.

More literary icons have been criminals than your high school English teacher might have led you to believe. Take Marlowe’s contemporary, Ben Jonson, who stabbed an actor in a street brawl. That’s right: Jonson, England’s first poet laureate, got his start by murdering a man in a swordfight. He barely escaped death by hanging for the crime, calling on an obscure legal precedent that said the executioner couldn’t hang a man who could speak Latin.

Then there’s Samuel Pepys, whose extraordinarily detailed seventeenth-century diaries are one of the most-often-cited primary sources of the English Restoration. More interesting—to me—is the fact that Pepys was arrested for high treason not once, not twice, but three separate times. And while none of these charges stuck, he did spend time under lock and key in the Tower of London for a different, equally splashy crime: piracy.

(Where is my ten-part miniseries about Pirate Captain Samuel Pepys, Netflix? Must I do everything myself?)

Robert Louis Stevenson, of Treasure Island fame, was arrested twice: once under suspicion of being a German spy, and once for a snowball fight that got out of hand. The French surrealist poet Guillaume Apollinaire was briefly—though wrongly—arrested for stealing the Mona Lisa. Thomas Malory, author of Le Mort d’Arthur, was most likely a notorious outlaw convicted of robbery, cattle theft, extortion, attempted murder, and church robbery.

There’s something about this list of canonized secret criminals that delights me to my core. We’re all used to the archetype of the stay-at-home author who sits by the fire with a cup of tea and composes grisly murder mysteries. I’m a broadly law-abiding writer myself, with little but a handful of parking tickets to my name. I have no desire to turn to murder, art theft, or piracy in my spare time—but these men did, and I find myself yearning to figure out why.

I also love the sheer rebellious pleasure of putting the fun back in classic lit. Every one of us could tell the story of a “great” book we hated entirely because we were forced to write a timed essay on it in English class. Knowing the salacious backstories of the men behind the canon re-genres those books, in a way. It feels like taking the dusty classics off the shelf and slapping a new, more colorful jacket on them—one that’s just as much mystery, thriller, or true crime as it is literary fiction.

As an author of historical fiction, criminal authors have one more powerful draw: we have access to their writings, and all the psychological insight that can yield. Sorry, Roland Barthes: when I’m writing biographical historical fiction about writers, “death of the author” is off the table. To write A Tip for the Hangman, I dove into Marlowe’s work and let my interpretive brain run wild. How much of the notoriously bloody Tamburlaine the Great reflected Marlowe’s own thoughts on revenge and justice? What can we learn about his espionage tactics from The Massacre at Paris? There’s no way to know for sure, but from a crime writer’s point of view, it’s too much fun not to speculate.

There’s a narrow line to walk here, of course. Some authors have committed crimes that seem endearing with a few centuries of distance: piracy, treason, espionage, getting entangled in a counterfeiting operation in the Netherlands. Other crimes are of a different stripe entirely: the kind that makes it difficult or distasteful to engage with the author at all. Take William S. Burroughs, for instance, who murdered his second wife and barely served time for it. Or Ezra Pound, modernist poet and notorious fascist collaborator during World War II. Or any number of writers through the ages who use the authority of their position to sexually harass or assault those with less power.

Beyond that, the phenomenon of the criminal author is almost entirely a function of white male privilege. The canon has only opened to women and people of color in the last century, if not the last few decades, so it’s no surprise the writers I’ve mentioned above are all white men. And it’s impossible to imagine a person of color committing any of the crimes I’ve described and escaping as lightly as these men did. Race, gender, nationality, class, religion—all the complicated facets of identity are deeply at play here, and it’s naïve and dangerous to pretend they’re not.

Just like any time the “bad boy” trope rears its head, it’s worthwhile to think about what behaviors it’s tacitly condoning, and at what point it starts to become a problem. Everyone will need to locate and draw their own line in the sand. For me, it’s a question of feel: as a woman of Jewish heritage, the anti-Semitism in Marlowe’s play The Jew of Malta is something I can look beyond for a good story; Pound’s chummy relationship with Mussolini is not.

Still, these caveats won’t dissuade me from luxuriating in the study of classic literature’s strangest criminals. The grist it provides for the fiction mill is unparalleled. It’s one of the best ways I’ve ever found to turn the marble busts of Literature’s Great Writers back into real people: human beings who made terrible choices, took risks that didn’t pan out, and maybe dabbled in piracy of a weekend.

And let me tell you, knowing all this would definitely have made tenth-grade English more fun.

*

My first encounter with the Russian mob occurred two-and-a-half years after the dissolution of the Soviet Union, in Istanbul. My new husband and I had traveled to Turkey and spent a week in a gloriously historic neighborhood, the Blue Mosque visible from our hotel windows. On our second night, we wandered across Galata Bridge, descended the steps to the waterfront, and chose a restaurant with a perfect view of the Golden Horn. Docked directly in front of this restaurant and sporting the tricolor Russian Federation flag floated a gigantic but peeling cruise ship, the name “Odessa” painted under a red star on its side. A single Russian family occupied nearly every table inside the restaurant—a man, his wife, his parents, her parents, multiple siblings, children, nieces, and nephews. They appeared to have been sitting for hours, the dishes before them already of the sweet and evening-snack variety.

We ate our kebabs while I tried to eavesdrop surreptitiously, even as we ourselves attracted quizzical glances. Back then, the only tattooed people in Russia were criminals, mostly men who had served time in Soviet prisons. Their tattoos, as in many underworld societies, had (still have) specific meanings. The reason we drew attention was that I was very obviously of Russian heritage and my husband, who could pass for Russian if he kept silent, had tattoos. As curious as we were about this party, so were they about us. Only when I got up to use the ladies’ did I realize everyone thought I was yet another Eastern European woman taking advantage of the newly opened borders to escape poverty and ply her wares on the shores of the Bosphorus, perhaps with her pimp. (A man followed me and made this assumption abundantly clear).

We stayed as late as we reasonably could, but the Russians were still eating. Much like a family on Thanksgiving who grows peckish a few hours after dinner, they requested fresh platters of kebobs and pilaf while their dolled-up children ran between the servers’ legs.

Throughout this entire evening, the family and various young men from neighboring tables paid homage to the man sitting at the head of the longest table. They asked him questions, and he would debate and answer. Then they’d drink a toast. Or they handed him something and he would pat them on the shoulder. Then they’d drink a toast.

Right before we called it a night, the man retrieved a softball-sized roll of US dollar bills, peeled off a couple hundreds and handed them to a waiter. The rest of the bills in that eye-popping roll were also hundreds.

Back in our hotel later that evening, I spotted two of the young men from the restaurant in the lobby, and the next night we bought them drinks, probing them for details. What we had witnessed would have been straight-up commerce in any capitalist country. But since the man with the wad of cash hailed from a county that only recently stopped punishing private enterprise with prison sentences, and still had no idea how to conduct itself capitalistically, the party we had inadvertently crashed was tied up with the criminal underworld. The young men confessed that their ultimate dream was to climb the mafia hierarchy and come to America.

Their cruise ship sailed from Odessa to Istanbul every few months, then the boss would send them and many others to buy everything in sight. Back in Russia, the cheap Turkish goods sold for huge profits. Russian money being worth nothing, this commerce was almost exclusively conducted in US dollars.

The reliance on dollars was not new and had evolved decades earlier when the black market began to flourish in the Soviet Union. Despite Stalin’s savage regime and the relentless hunt for “spekulants” (people who bought and sold goods on the black market), and “valuta” (foreign currency), absolutely everyone in the Soviet Union, at one point or another, bought or sold something on the black market. Even my father, who prided himself on being financially naïve, bought matzoh for us on the DL, because there was no other way to buy it. Other things that appeared in our household on the DL: bananas, caviar, pink patent-leather shoes for me, watercolor paints. There was probably more, but I was a child and not privy.

Private enterprise was underground yet universal in the USSR, often criminally organized, sometimes not. With an increase in foreign tourism in the 1950s, resourceful young men could be found circling tour groups, whispering, “For sale? For sale?” Anything a tourist had could translate into profit: blue jeans (of course), but also chewing gum, records, cassette tapes, books, shoes, underwear, cosmetics. Literally everything from the West was worth money. This buying and selling of all things foreign became known as “fartsa” (from “for sale”) and the men churning this commerce were called “fartsovschiks”. It was highly illegal, very dangerous, but the thrill was irresistible. It wasn’t just the money. It was the excitement of laying hands on a Beatles album or tasting a stick of Juicy Fruit. It wasn’t just that commerce itself was forbidden, but western music, food, clothes, magazines—for with those came foreign ideas. And those ideas proved deadly to a totalitarian state.

This underground commerce bubbled under the control of loosely connected criminal brotherhoods known as Bratvas. Regular citizens did their own bartering, but the more organized efforts belonged to Vors (Thieves), officially known as Vory v Zakone, or Thieves-In-Law. These Vors served time in prisons, received their specialized tattoos, and eventually were the cause for the bemused glances my husband received at a mob-dominated restaurant at the foot of Galata Bridge.

In the 1970s and ‘80s the Soviet Union relaxed its borders for citizens of non-Russian nationalities, resulting in a quarter of a million Jews rushing to leave while the leaving was good. An astonishing number of those immigrants settled in Brooklyn, in Brighton Beach, a community that had already been Jewish for half a century. I’ve read speculation that the Soviet Union opened its borders to rid itself of its criminal element, but plenty of criminals remained behind. A connection between the old world and new ensued, only to strengthen after the fall of communism in 1991.

Brighton Beach, or Little Odessa as it came to be known, very quickly birthed a robust criminal brotherhood of its own. Here, they were often of Jewish, Ukrainian, and Georgian descent, soon joined by men from the far-flung Soviet republics. Meanwhile, the disintegrated ex-Soviet state had many desirable commodities to sell and a power structure having more in common with the underworld than a First World democratic state should. Arms (including nuclear), planes, tanks, anything that wasn’t nailed down was soon for sale on the global black market.

The Vors were not at all averse to working with other criminal organizations. In 1997, a Vor nicknamed Tarzan plotted to sell a Soviet diesel submarine to a Colombian cartel for the purpose of smuggling cocaine. More recently, a 2017 racketeering case against the Shulaya gang out of Brighton Beach was so wide ranging in scope the indictment listed 33 defendants and spanned the continental US. The indictment details, among other things: violence, extortion, the operation of illegal gambling businesses, casino fraud, identity theft, credit card fraud, and trafficking of stolen goods. There is also prostitution, slot machine hacking, drug trafficking, a murder-for-hire plot, a plot to have a female member of the enterprise seduce victims, then chloroform (!) and rob them. They stole 10,000 lbs. of chocolate from container ships. Did I mention the kidnappings or the money laundering—using a fraudulent vodka export-import business (what else?).

Speaking of money laundering, I’ll end on one more personal experience. The last time I visited my family in Moscow, we had to exchange money. Being cautious Western tourists, we decided to do this at a bank. The bank was guarded by visibly armed men. When we finally made our way into the lobby, we were told that the bank would not take our dollars, though it would happily sell dollars to us for rubles at a laughably worthless rate. We gave up and descended into the metro, where pop-up kiosks exchanged money unofficially. There too, the clerk refused to accept our bills because some had markings or creases. Frustrated, we turned around, only to have the woman behind us in line shrug and say she’d buy our dollars because she would, quote, “have to give it to the gangsters, anyway.”

The Russian mob is local and global, multi-lingual, technologically advanced, but not against using low-tech, brutal techniques. Its members are atheist, Jewish, Muslim, and Christian, their culture a greater bond than their religious differences. As an organization, it has existed since the eighteenth century and has adapted and thrived through every historical upheaval.

As with all criminal organizations, it is filled with bad people doing awful things. But it’s the demented quality of their undertakings that makes it such outrageously great fiction fodder.

*

When Taryn Cornick’s sister was killed, she was carrying a book. People don’t usually take books when out on a run, but Beatrice must have planned to stop, perhaps at the Pale Lady, where she was often seen tucked in a corner, reading, a pencil behind her ear.

The book in the bag still strapped to Beatrice’s body when Timothy Webber bundled her into the boot of his car was the blockbuster of that year, 2003, a novel about tantalising, epoch‑spanning conspiracies. Beatrice enjoyed those books, perhaps because they were often set in libraries.

The Cornick girls loved libraries, most of all the one at Princes Gate, which belonged to their grandfather, James Northover. Beatrice was seventeen and Taryn thirteen when their grandfather died. The family had to give up the debt‑encumbered house—though Grandma Ruth stayed on in the gatehouse while she continued at her vet’s practice. It was Grandma Ruth whom Beatrice was visiting when Webber found her.

Beatrice and Taryn’s parents were separated. Basil Cornick was in New Zealand, playing the bluff fellow in a fantasy epic. Addy Cornick had been struggling with illness and was dispiriting company. Taryn would spend some of her holidays with her mother, then stay with friends. She never went near Princes Gate, because she couldn’t cope with the changes. A farm conglomerate had taken over the estate. The new owners left the last of the wetlands intact, and the plantation forest with its kernel, a copse of ancient oaks. But the stone walls were dis‑ mantled to make long fields with nothing to impede the big harvesting machines—not walls, or drainage ditches, or the hawthorn hedges the foxes had followed.

The library had already gone, broken up before the sale. James Northover’s books passed into the hands of the owners of antiquarian bookshops, except a few long‑coveted items that went to his collector friends, perhaps including the ancient scroll box known as ‘The Fire‑ starter’, because it was said to have survived no fewer than five fires in famous libraries.

So, the book bumping against Beatrice’s shoulder blades as she took her last steps was one of those set in old museums and libraries. A book with a light in its long perspective, like the light of a grail. A book with scholarly heroes and hidden treasure.

Beatrice was running in her baggy sweats and bouncing backpack. It was autumn, and there was a light mist. The road between St Cynog’s Cross and the village of Princes Gate Magna was thickly covered in fallen leaves, its surface amber but for two black streaks where the leaves had been chewed up and tossed aside by the tyres of passing cars. The road was quiet. Beatrice wasn’t wearing headphones. She moved off onto the verge when she heard the car. The mist began to sparkle, and the reflectors on Beatrice’s shoes flashed as the headlights caught them.

Whenever a restless night summoned her sister—her grey sweats and swinging ponytail—Taryn never found herself on that road. She was always in the car. In the driver’s seat. She was the murderer, Timothy Webber. Taryn thought this might have been because she had spent so much time wondering why Webber had done it. Wondering how anyone does a thing like that.

The trial was held a year after Beatrice died. Taryn attended and became familiar with every detail of what happened—or, at least, what was known.

Webber’s car hadn’t clipped Beatrice because she wasn’t far enough off the road. The police photographs showed a curved tyre track in the black mud. They showed how far he had swerved to catch her. There were no skid marks, because he’d braked already, reducing speed not to pass safely but to hit Beatrice hard enough, he hoped, to subdue her. His car cracked Beatrice’s pelvis, and a roadside oak her skull. He stopped, got out, and scooped Beatrice up from where she lay in the lap of some tree roots. He put her in his boot.

Webber’s lawyers let him take the stand, perhaps hoping his fecklessness would convince the jury that his actions lacked malice. He told the kind of feeble story kids concoct when they’re caught out. He said he put Ms Cornick in his trunk to take her to hospital. But—the prosecution asked—wouldn’t most people place an injured person in the back seat, or not move her at all and wait to flag down the next car?

Webber said he’d been too afraid to wait for someone to come along. It was a quiet road. He wasn’t carrying a phone. It would probably have all gone better for him, he said, if he’d just driven off and had to face a charge of hit‑and‑run instead of this one. ‘But I couldn’t do that.’ He screwed up his mouth in an expression of apology. ‘Why I put her in my trunk rather than my back seat must have been because she’d soiled herself and was a bit of a mess.’

The jury moaned in anger.

Timothy Webber had been charged with manslaughter, not murder, because, the prosecutor explained to Beatrice’s family, it was very difficult to prove intent. The police didn’t want to risk him getting off altogether. Webber wasn’t a bad character on paper. He had a job. He was an honest and reliable worker. He had no criminal record. He had friends and family. He hadn’t been equipped for an abduction, wasn’t carrying rope or duct tape. He hadn’t lined his boot with plastic. He made no attempt to conceal anything, leaving Beatrice’s thrown shoe where it lay, on the road, pointing back the way she’d come. He ran her down, but it was difficult to prove conclusively that it wasn’t an accident. He may have bundled her into his boot and driven off, but in the end, all he had done was take her another two miles in the direction he’d been going, before performing a U‑turn to drive to his sister’s house. His sister called an ambulance. She said to the paramedics, then to the police, ‘Tim just isn’t very bright.’

Beatrice was dead when the ambulance arrived.

Taryn wanted to know what it had been like for her sister, locked in the dark of Webber’s car boot. After the trial, a medical intern friend took a copy of the coroner’s report to his colleague and arranged a meeting so the neurologist could tell Taryn how it might have been.

‘It’s unlikely your sister regained consciousness after the impact,’ said the neurologist. ‘She had a skull fracture, compression fractures in two cervical vertebrae, and the crucial thing, a brain stem injury. It was the swelling in your sister’s brain stem that killed her—through uncontrollable blood pressure and disruptions to the normal rhythms of her heart. If you’re wondering whether she suffered, she almost certainly knew nothing from the moment the car ran into her.’ The neurologist’s look said it all—how he respected Taryn’s need to know. How this was all he could tell her. How he knew it could never be enough.

What he said helped Taryn believe what the jury had believed—that Webber wasn’t a killer with a plan. He hadn’t stalked her sister, and he wasn’t prepared. He’d only nurtured a fantasy, then surrendered to an impulse. He pulled the wheel to the left. He picked Beatrice up. But she’d soiled herself and wasn’t what he had wanted—a woman thrown down, stunned and helpless. It all went wrong for Webber. He hadn’t felt what he’d hoped to feel, or gotten to do what he’d dreamed of doing, and he couldn’t cope with any of it. And, because he didn’t follow through and rape the woman he’d injured and abducted, maybe that was why he was able to stubbornly insist on his innocence. He hadn’t meant to hurt Beatrice and was indignant that anyone would suggest he had.

He just ran into her, then panicked. ‘I was upset,’ he said—almost as if he expected the court to kiss him better.

Webber was convicted of the charge of manslaughter and sentenced to six years. Five with good behaviour.

I’ll be twenty‑five then, Taryn thought. She hoped five years would be long enough for her to move on—as people put it, not seeming to under‑ stand how she was always on the move, even in her dreams, driving along the amber road as the mist began to sparkle.

As it was it took most of that time for Taryn even to learn to hide her rage. She wanted to keep her friends—not that they were much use to her now, but she understood that they might be one day. In time she’d feel human again, and part of some civil world.

To starve her rage, Taryn stopped talking about Beatrice, not just about what had happened—everything. There were stories she would tell about her childhood where she and her mother and father, grand‑ mother and grandfather would be there, in the room of the story, with a ghostly absence, the now unmentionable Beatrice. Taryn couldn’t separate her sister from her death, from the mark on the oak at the fringe of the forest. In Taryn’s memory, her sister was a tender wound, Beatrice’s whole life stained with the blood she had shed inside her own head. Taryn was angry—burned and pitted by anger like acid. Other things came with the anger: fearlessness, recklessness, chilliness, insolence.

When Taryn met her husband, Alan Palfreyman, she wasn’t after a man of any sort, let alone a rich one. She only wanted something to eat, a glass of wine, a comfortable place to sit. She’d been caught in Frankfurt Airport by a cancelled flight on a budget airline. She’d had a holiday in Greece, on a beach she went to only at dusk, because the sun was fierce and her skin very fair. She was on her way home—sea salt still powdering her faintly mauve‑shaded white skin; salt in her hair too, so

that it was curling and almost black in its thicknesses. Taryn was superficially tired and very hungry, so she staked out the first‑class lounges and shamelessly followed one man, a self‑contained individual whose passing glance had registered not exactly interest but passive admiration, as if she were a fine watch and he had enough watches. Taryn fol‑ lowed him up the escalator, and when he was showing his membership card to the woman at the front desk of a hushed and scented lounge, and that woman was saying, ‘Good afternoon, Mr Palfreyman,’ Taryn gently slipped her arm through his and said, ‘Mr Palfreyman and guest.’

Alan looked at her in surprise but consented. ‘And guest.’ And they were through, arm in arm.

Taryn was twenty‑three when she married, the same age Beatrice had been when she died. Webber had three years of his sentence left to run—if he was serving the full sentence. Taryn’s mother had gone. Addy Cornick had been battling breast cancer for years and was in remission when Beatrice was killed. Shortly before Webber’s trial Taryn’s mother had one of her twice yearly check‑ups. Taryn went with her mother for the follow‑up appointment. When Addy Cornick’s oncologist told her she was still in remission she wept, not with relief, but bitterly, like someone who has had the worst possible news. She wiped her eyes and shrank in her chair, saying to herself, over and over, ‘Do I have to keep doing this?’ Meaning, ‘Must I go on living?’ Then, once the trial was over, Addy lost ground. She gave up. She seemed to be in a hurry to leave the world before her daughter’s killer returned to it.

For much of that period Taryn’s father was in New Zealand. Basil Cornick had a role in what he invariably referred to as ‘a juicy fantasy franchise’. It made him a lot of money, though the lonely interactions with imaginary friends and foes in front of a green screen almost robbed him of his lifelong joy in acting. Taryn’s father returned for her wed‑ ding. He gave her away. He also gave a speech and got the guests to raise their glasses to Beatrice: ‘My elder girl, who was tragically taken from us by violence, four years ago.’

Taryn carefully avoided looking at her husband. He knew she’d had a sister, and that Beatrice was dead. But she’d only told him that Bea was hit by a car. Perhaps, when her father was making his overly informative toast, she should have met Alan’s eyes so he’d at least see her wondering what he might be thinking. Taryn had, after all, wanted to share her life. To at least have a roost, as if she were a solitary ocean‑going bird looking for somewhere solid to set down, no matter how bare and exposed it might be.

On her wedding night Alan was still a little under the shadow of the loneliness he’d felt as he sat, his face stiff with shock, hearing his bride’s rather off‑putting actor father outline the appalling story of her sister’s murder. The speech had been so strange, somewhere between sentimental and perfunctory. Sitting with his bride on a splendid hotel bed, that loneliness wasn’t a thing Alan could recall in its horrible purity. He re‑ fused it, because he loved Taryn, the mysterious woman with wounds so deep she hid them from him. He hadn’t yet begun to think, Who am I to her that she hides a thing like that from me? Alan Palfreyman thought too well of himself for that.

Once they were finally alone, Alan took Taryn’s face between his hands and looked into her eyes. ‘You’re so sad, Taryn, and haunted, and out of step with others.’

Even Taryn could see this was true. She was always studying the world, not rapt or curious, but patient and dutiful, as if the world was something she’d paid good money to see. She was studying it now too— in the shape of Alan’s tender, troubled face. She was listening to the whisper of his smooth palm on the skin of her jaw, as he gazed at her and said, ‘Who are you, Taryn?’

__________________________________

Personally and overall, I found this vid by Sanderson to be the most useful and pragmatic of all the vids reviewed so far--precisely the kind of advice I would expect from a truly successful author. My takeaways as follows:

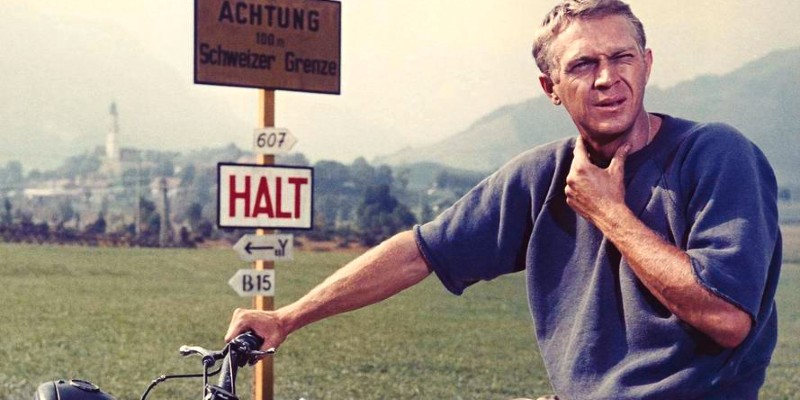

The fifth-floor hallway was darker than reported, and there was an awkward dogleg near the stairwell that their local recon hadn’t bothered to map; it smelled of garlic, mold, and dry rot even though the hotel was billed as a Byzantine five-star. A milky Mediterranean twilight bled faint from hidden recesses along the ceiling, enough to cast a glow but not overly expose the shadow gliding through the shadows toward its target.

A woman, unremarkable, if a little boxy, hip to shoulder. Here on business, you might think, not worth a second look. Black slacks, T-shirt and unstructured blazer, wireless earpiece, and Zero Halliburton briefcase.

She approached a doorway with a curious surfeit of caution, stepping to one side of it while preparing to knock. But then she hesitated, stared uncertainly at the brass digits fixed to the door— six two seven—and was momentarily unable to make sense of them. A voice in her earpiece hissed, “What’s wrong?”

She shook her head, forgetting that the voice couldn’t see her; she glanced across the hallway at the next doorway, momentarily paralyzed with doubt.

“Suite number,” she murmured, with a calm she didn’t feel. “Double-check for me?” “Seriously?” In her earpiece, an annoyed whisper: “Shit, man, did you fucking forget it?” She didn’t answer him but felt her cheeks flush hot because yeah, she had.

“Stand by.”

She waited as papers rustled on the other end of her comm, a clock in her head ticking away precious seconds that she knew, from long experience, she’d regret losing however this went down, at which point a door across the hall but just behind her—six two six—opened to reveal the naked, pale, middle-aged Chinese American asset she’d been sent to retrieve, a towel wrapped around his waist and a frown on his face. Their eyes locked.

There’s the plan that you make going in, and then there’s what really happens—the shit storm.

Rarely do they align. “Can I help you?”

No. It was supposed to be the other way around. But on the love-tossed bed in the room behind the towel man, a pretty, naked woman was reaching to a side table and a big black Glock that surely had been stowed in its drawer for a contingency just like this one.

The woman in the hallway felt the familiar slowing of time she often experienced at the initiation of conflict. The clarity, the narrowing of focus, her pulse in her neck, a slight dissociation, as if she were watching what was unfolding rather than actively participating in it.

She was across the corridor and falling to the side and away from the six-two-six doorway, her arm wrapped around and pulling the towel man down with her as bullets from the naked woman’s gun splintered the jamb, slipped hot past their faces, and blistered plaster off the wall opposite. She felt them tear into the tactical vest under her T-shirt and bang off the metal briefcase she had raised as a shield. The narrow corridor came alive: voices, Turkish, other doors flung wide, a volley of panicked gunfire as red tracer dots from short-stock automatics searched the gloaming for her. The towel man was shrieking. She felt the warm wetness where a bullet had grazed her neck,

just below her ear.

Stress, but no panic. She whispered evenly, “Stay with me, Scott, okay?” Their Halliburton shield burst open, she lost her grip on it, and bullets tore the cash bundles inside into a flurry of pale confetti that smelled like burned rice.

She hit the floor hard. The stun grenade that exploded next was too close to her, with a roar of blinding light she’d been unprepared for.

The three-op backup who had rolled into position beyond her waited for sight lines to clear so they could cut the Turks down with little fanfare.

Close your eyes. Cover your ears. With the asset in her arms, she had been unable to follow any operational protocol. A searing scree deafened her. Curled around her man, protective, blood leaking from her neck wound, she felt dizzy, head filled with glue, and sensed a lateral movement.

The naked woman. Glock in her outstretched hand aimed point-blank down at the asset.

His dad body wasn’t as heavy as she expected. Or maybe it was simply the adrenaline of fear. She levered him safely to one side, rotated while pulling the sidearm from her hip—took a breath— and aimed center mass before tapping the trigger twice.

The naked woman dropped like a puppet whose strings had been cut.

Shredded bills and bits from the broken briefcase were still wafting down on them. No more than eleven seconds had passed. It had happened so fast that the spray of the overhead sprinklers triggered by the stun grenade only now began to rain.

Her thinking was splintered and unreliable; her eyes felt fried, the hallway even thicker with the smoke and the mist. She struggled to sit up. The naked woman lay dewy and unmoving on the threadbare carpet, ivory skin between augmented breasts ruined by the two puckered puncture wounds where the bullets had made entry.

There was movement around her. She heard but couldn’t understand the voices, as if she were underwater, but when her hand found his shoulder, she felt the pounding of the sobbing towel man’s heart.

“Let’s get you home,” she heard herself murmur.

There were hands under her arms then, and she stood, finding her balance; the rank lukewarm water that ran down her upturned face felt heaven sent. The backup team got their trembling towel- clad asset to his feet and trundled both of them to the emergency stairwell and away.

Her own pulse was steady, stubborn; she’d survived.

__________________________________

One morning, not long after my first novel, Finding Jake, was published, I walked my kids to the bus stop. As I stood just outside a pod of my neighbors, watching our kids roll away, one of the dads stepped up to me. Understand, the exchange was nothing but friendly. Conversational, even. But it was the beginning.

“We really enjoyed your book,” he said.

“Thanks,” I said, my eyes lowering, a little embarrassed by the attention.

“Yeah,” he said, staring at me. “It was really cool to read a story with so many familiar details.”

I didn’t get it at first. Social interactions have always confused me to some degree. The nuances lost until I have time to think about it. When he continued, I picked up my first hint.

“My wife really found it… interesting.”

I slipped out of the conversation and went home. Later that day, I ran into another neighbor as we walked our dogs. I saw the hunger in her eyes as she approached.

“(Name withheld for my own safety) is mad at you,” she said.

She was talking about the wife of the man I had spoken to that morning. I had a sense of where this was going, but I had to ask.

“Why?”

“What you wrote in your book about her,” she said.

I took the time to explain myself, knowing this conversation would get back to her. Regardless, we didn’t get their Christmas card that year, or any year since….

Writing books is truly a great job. The commute is nonexistent. The schedule is fairly flexible. The physical strain is no worse than a bout of carpal tunnel syndrome. But there is a dark side. A very true and personal danger. One someone should have put in the job description. An occupational hazard that should come with a warning label. When you write dark stories, particularly one about a serial killer, people certainly start looking at you a little differently.

Just for background, here are the topics covered in each of my four published novels—a school shooting, domestic terrorism, alcoholism and abuse, and my newest book due out in February, Let Her Lie, a serial killer. If you lived next door to me and you read any of the four, you might give me the side-eye. You might install a camera outside your house, surreptitiously pointed in my direction. You might not invite me into the carpool for our daughters’ dance class. And, I guess, I can’t blame you.

The question is simple. How can a normal person come up with stuff like that? If they can, they must think about it. And if they think about it, how far is that from actually dabbling, really? Right? Sometimes I imagine my neighbors practicing the interview they will give to the local news station when the truth comes out. When I’m finally caught.

Maybe that would make a good book. The author next door acting out his darkest fantasies. Like a domestic Basic Instinct. But it’s just not believable. I’m pretty much a softy. I don’t like setting mouse traps. If I accidentally walk out of the grocery store and notice I have something under the cart that I forgot to pay for, I head back in. I even hold doors for the elderly, as hard as that may be to believe.

So how did this happen? Why do people I know come up to me with a sheepish laugh and ask how I come up with such dark ideas? How did I scare all of the people around me? It’s simple. Just as people see me in my stories, they see themselves in my characters. If I’m writing about real people, I can’t be making up everything else, right?

I’ve provided this exact explanation so many times. To my mom after she got upset with me because of the father character in my novel, The Perfect Plan. To my son’s teacher after the cover of Finding Jake came out looking eerily like him. And at almost every festival or event I’ve attended when an audience member comments on my newest book being a little more “disturbing” than my last. The short answer is, I make it all up.

In reality, this misunderstanding, in my opinion, all comes down to the conception of a character. My life is pretty boring. Certainly not something that would make a plot for a novel. And, I apologize in advance, the people in my life aren’t much more thrilling. But I do something that causes this confusion. When I start a book, I have a character in mind. This person is utterly and completely fictional. This person has to do some crazy things, survive life and death situations, to get to the end of the story. Like I said, this person is absolutely no one I know.

Then I start writing. It is the little details that pop up. I might set a scene at someone’s house, even. Or my character might find his/her self in a real-life situation. These mundane moments anchor a story. Give it a sense of reality. And I blatantly steal them from my real life. In my first book, I included a play date that pretty much happened. In my most recent book, my main character struggles with a sense of purpose that might be my own. These descriptions, or actions, or settings cause most of my agita. For those around me recognize them. And when they do, they identify with that character. They think I wrote them into the story. But I’ve never done that. Every character I’ve written is their own person. And no character I’ve written has a single person as their basis.

Back to the story that began this discussion. What, you might ask, made my neighbor think I wrote about her? What made her so angry that she has yet to forgive me? It’s a delicate answer, but I’ll do my best. In my first book, one of the main character’s neighbors has a physical attribute. Or, more specifically, an augmented physical attribute. From what I’ve come to understand, my neighbor has a similar… augmentation. A fact that I was blissfully unaware of until that fateful day. And the absolute truth, though I’ve tried not to say it for fear of offending her or anyone, I never thought of her once while writing that book.

So, to that neighbor, and to all those that I’ve frightened, let me leave you with one plea. Please consider that the imagination we try to cultivate and grow in our children might well be alive in some adults. They are, after all, just stories. Stories that I hope prompt a discussion about the state of society and culture.

*

Another week, another batch of books for your TBR pile. Happy reading, folks.

*

Mick Herron, Slough House

(Soho)

“Herron has certainly devised the most completely realised espionage universe since that peopled by George Smiley.”

–The Times (UK)

Ben McPherson, Love and Other Lies

(William Morrow)

“McPherson dramatically highlights the tensions between Norway’s native and immigrant populations as the plot builds to a devastating conclusion. This powerful, thought-provoking novel deserves a wide readership.”

–Publishers Weekly

Alex Tresniowski, The Rope: A True Story of Murder, Heroism, and the Dawn of the NAACP

(Simon & Schuster)

“This suspenseful, well-written true-crime tale will be an eye-opener for anyone who assumes that after Reconstruction, lynching remained a serious threat only in the South. High-velocity historical true crime.”

–Kirkus Review

Michael Koryta, Never Far Away

(Mulholland)

“Well-developed characters enhance the high-octane plot. Fans of nail-biting suspense will be in heaven.”

–Publishers Weekly

Linda Castillo, A Simple Murder

(Minotaur)

“Murder in Amish country has a certain added frisson, and Castillo’s the master of the genre.”

–People

Emilya Naymark, Hide in Place

(Crooked Lane)

“An original, satisfying roller-coaster ride for domestic suspense fans.”

–Publishers Weekly

C.J. Tudor, The Burning Girls

(Ballantine Books)

“Tudor . . . strikes again with another thriller filled with twists and turns right up to the mind-bending ending.”

–Library Journal

Alison Epstein, A Tip for the Hangman

(Doubleday)

“[T]hrilling and romantic . . . Epstein successfully evokes both the beauty and the brutality of 16th-century England.”

–Historical Novel Society

Bryan Reardon, Let Her Lie

(Crooked Lane)

“A virtuoso exercise for serious players determined to keep playing each other to the bitter end.”

–Kirkus Reviews

Lucy Atkins, Magpie Lane

(Quercus)

“Lucy Atkins excels at creating highly intelligent, slightly eccentric outsiders. I was completely immersed… and preoccupied, and appalled, by such credible characters. I loved it.”

–Sarah Vaughan