-

Posts

4,576 -

Joined

-

Last visited

Posts posted by Admin_99

-

-

Why are imaginary friends so creepy? What is it that’s so unsettling about the sight of a child confidently babbling away to thin air?

Stephen King wrote, “The root of all human fear is a closed door, slightly ajar.” The things we can’t see that are almost always more frightening than those we can. The idea of a threat that the child can see but the adults around him can’t is recurrent in the horror genre because it’s so effective: think The Others, The Sixth Sense

My debut novel, The Woman Outside My Door, owes a lot to horror. It’s situated firmly in the psychological thriller and domestic noir genres, with themes of mental health, motherhood, and homemaking and dark threads of danger needling throughout. But despite the novel belonging on the psychological suspense shelf, my love of horror found its way onto the page. The Woman Outside My Door has a ghostly, Gothic feel that it wouldn’t have if I hadn’t grown up binge-reading Stephen King and watching movies like The Orphanage and The Shining over and over again.

There is so much about I adore about ghost stories. The dramatic, evocative settings, the big Gothic houses, the isolated locations and things-that-go-bump-in-the-night. The compulsive uncertainty—is there or isn’t there?—that’s introduced with the first creak in an empty corridor. If you’re watching a horror movie, you already know there is, by virtue of the story having been billed in that genre, but we watch anyway, the same way we watch romances for the will they, won’t they storyline even though we already know the answer. In The Woman Outside My Door, I introduce an is there or isn’t there question in the opening pages that isn’t answered until the very end—is there or isn’t there an “old lady” in the park who has been talking to seven-year-old Cody? It was only after I finished the book that I realised I’d been unconsciously echoing that ghost story structure.

One reason children make such fantastically frightening literary devices is their tendency toward bald statements. There’s a moment in Jordan Peele’s brilliantly clever second horror film, Us, that scared me half to death the first time I saw it. A young boy, Jason, approaches his parents just after lights-out and says to them, “There’s a family in our garden.”

Why is this so unsettling? Why is it so much more effective to have Jason deliver this line than any other member of the family? It was an undeniably excellent artistic choice, because neither the adults nor Jason’s teenage sister would ever describe what they saw in such a manner. An adult might say, “There are people in the garden.” An adult might add, “We should call the police.” But Jason doesn’t jump to that. Children don’t interpret what they see; they report it. There’s a family in our garden. There’s no analysis of the situation, no attempt to rephrase it into something that makes more sense. The end result is the kind of stark statement that make adults uncomfortable.

In the first chapter of The Woman Outside My Door, Cody’s mother catches him eating a lollipop and asks where he got it. He tells her, “The old lady gave it to me.” When she presses him, “What old lady?”, he replies simply, “The old lady in the bushes.” This was the first scene that formed in my head. I heard the conversational tone in which Cody delivered the line that made his mother turn cold. I saw the icy park where they stood, the deserted playground, the frost-tipped branches. I saw Cody pop the lollipop into his mouth and run off toward the playground, unaware that what he had said had shaken his mother to her core. Right from the beginning, Cody’s innocence and powers of imagination were core facets of the plot.

I’ve always been more frightened by the things that happen just off-screen. That which can be seen can be confronted. But the unknown—what’s behind that door? What was that sound?—can’t be faced head-on. Using children as a plot device allows us to play around with this. Kids see a slightly different world. We can’t always be sure whether they are reporting on something that happened in reality or on TV, if it was described to them by a classmate or even happened in a dream. There’s a family in our garden. The old lady gave it to me. What’s really there?

There is a scene in The Others in which Nicole Kidman’s character notices her daughter’s hand, playing with a toy, is not the smooth-skinned hand of a small child but the wrinkled hand of an old woman. The tension of that moment, as she crept up behind the small figure that sang in her daughter’s voice, stayed with me for a long time. The anticipation of the approach. A closed door, slightly ajar.

I didn’t intend, when I sat down to write The Woman Outside My Door, to use horror movie tropes to create a spooky psychological thriller. It was during the editing process that I became aware of how overtly eerie some of the scenes were, how creeping the sense of danger. That was when I realised that all the time spent re-reading Gothic novels and watching horror movies had all been part of a puzzle I didn’t know I was putting together, and it had all added up to this.

*

-

Although I’ve produced a book or two a year for the past thirty years it’s a truth still to tell that publishers continue to struggle to slot my output into a specific genre. You might ask what is a genre other than a label made up for the purposes of marketing and easy introduction. It rarely encapsulates everything that goes on in a book, is used simply to make a sale quicker and more achievable, and I guess there’s nothing wrong with that.

However, doesn’t it leave us wondering what we might be missing if we “never read crime” or we “scorn romance” or “wouldn’t go near science-fiction”? I can’t imagine there’s an author alive whose only real concern when writing a book is to be true to the story. Trying to make things conform to a given genre is constricting in a way no self-respecting writer would ever allow. True, the main character might be a detective, or a lawyer, or a British redcoat at the time of the Revolution, but that is never where he or she begins and ends.

Fortunately my books have managed to find their way through to the shelves in spite of not settling into recognized genres, often because someone has just decided to slot it into one that fits at least some of the story. I guess this isn’t a bad way to go, at least it’s out there and even if it isn’t in the category you think it should be in, going cross-genre can be an extremely effective way of reaching readers who might not otherwise pick up “that sort of book.”

The most uplifting reviews I receive are those that say ‘I’ve never read this author before; the story was nothing like I expected—definitely going to read more.’ (This can often have more to do with the jackets than the genre, but that’s for another time.) These comments usually follow me writing for a publication such as this one, with crime not being my natural home even though it features large in many of my books. However, I wouldn’t call myself a crime-writer for the simple reason that I see people, situations, stories as so much more than the act that pins them to a single misdeed, even if it is murder.

I believe it’s hugely important for new writers, especially, to be brave enough to write as expansively and truthfully as their fertile imaginations will allow. Trying to conform is only ever going to be restrictive. What matters is understanding that story is always king and characters are there to serve in the most effective way possible, while genre doesn’t really come into it until the creative process is over.

Below is a short list of books and authors who, for me, fall into a cross-genre, or even genre-less category. Some you will know because they are primarily marketed in a favoured genre, others you might not, because they have been published under other labels.

The Bernie Gunther series of books by Phillip Kerr are, for me, classic examples of cross-genre fiction. Gunther might be a big, burly German detective, making the stories fit easily into crime, but they are also gripping historical tales, sexily-romantic and the comedy is laugh out loud. (For Audio fans Jeff Harding’s narrations of these books are in a performance league of their own.)

Suite Francaise by Irene Nemirovsky. The author’s ambition here was to create a “symphony” of five novels, but she only completed two before she was arrested by the Nazis, taken to Auschwitz and never came back. Her daughters found the manuscripts many years later and they were published as a single book although they tell two very different stories. The first is of war time horror told with wonderfully wry observation of the escape from Paris, and the second is a haunting and extremely subtly told love story.

The Lymond Chronicles by Dorothy Dunnett is a series of six books that weave through every genre ever known and perhaps creates a few of its own. The writing is unusual, unique even, the settings are spectacular in an historical sense, and the stories of crime, treason, horror, supernatural forces and cunning are like nothing I’ve read before or since. They also tell one of the most powerful love stories I’ve ever read.

The Expanse novels by James SA Corey are gripping sci-fi but also profound, political novels. One of the things that struck me the most is the character of Marco Inaros, who is an incredibly dangerous man in a way that has a great bearing on the current mess we are in in the U.K. and the US. He’s a person who is completely incapable of admitting that he’s made a mistake or taking blame for anything; there is no such thing as objective truth as far as he’s concerned…

Daphne du Maurier—can you imagine which genre she’d fit into were she first being published today? Most likely she’d end up in “literature” which is fine, but not fertile ground for new authors. Her works are so full of darkness and mystery, immorality, the most sinister of crimes and some terrifying mind games. And let’s not forget the romance.

Jodi Piccoult is often lumped into the categories of “Commercial Fiction” or “Women’s Fiction” almost derogatory terms these days that set books up as fast and easy reads of a throwaway nature. On the other hand, being seeded into these genres can help to get more copies out there and build an author’s name going forward, although it’s debatable whether the author goes on to acquire the reputation they deserve. Piccoult often allows her detailed research to get in the way of the story, but there’s no doubt that she covers just about every genre, even including fantasy, and the quality of her writing is far more literary than is generally recognized.

*

-

Another week, another batch of books for your TBR pile. Happy reading, folks.

*

Christina McDonald, Do No Harm

(Gallery Books)“McDonald offers a painful look at two hot-button topics: the desperate opioid crisis, and a system that allows the cost of cancer pharmaceuticals to extend far beyond the reach of so many. Is what Emma does an unforgivable betrayal of her medical oath, her husband, and herself? It will be up to the reader to decide if the ends justify the means.”

–Booklist

Charles Finch, An Extravagant Death

(Minotaur)“Lenox’s latest adventure has humanity, heart, and humor; it offers a captivating glimpse of America’s richest citizens in the late 1800s; it delivers a gripping and cleverly plotted mystery; and, of course, Lenox remains a thoroughly charming lead character. A pleasure to read on every level.”

–Booklist

Andrew Mayne, Black Coral

(Thomas & Mercer)“Mayne’s portrayal of the Everglades ecosystem and its inhabitants serves as a fascinating backdrop for the detective work. Readers will hope the spunky Sloan returns soon.”

–Publishers Weekly

Rio Youers, Lola on Fire

(William Morrow)“[A] rocket-fueled crime thriller . . . . Fans of full-throttled cinematic action-fests of the Long Kiss Goodnight variety are in for a treat.”

–Publishers Weekly

John Marrs, The Minders

(Berkley)“This page-turner never sacrifices the characters’ humanity for the sake of plot. Marrs has definitely upped his game.”

–Publishers Weekly

Helen Cooper, The Downstairs Neighbor

(Putnam)“[A] heart-pounding debut…Even avid suspense readers won’t be able to predict all the twists. Cooper is off to a strong start.”

–Publishers Weekly

J. A. Jance, Missing and Endangered

(William Morrow)“Fans of police procedurals with a Southwestern flair will love Joanna’s determination to manage marriage, motherhood, and policing in this 19th ‘Joanna Brady’ book.”

–Library Journal

Mark Greaney, Relentless

(Berkley)“Vivid action scenes…this is still a must for espionage thriller fans.”

–Publishers Weekly

Hope Adams, Dangerous Women

(Berkley)“A historical episode artfully adapted in a bleak tale that offers glimmers of hope for women discarded by society.”

–Kirkus Reviews

Charles Todd, A Fatal Lie

(William Morrow)“This is a series, written by a mother-and-son team under the Charles Todd pseudonym, that shows no signs of slowing down. As always, this one combines crisp plotting with stylish prose. Ideal for historical-mystery devotees.”

–Booklist -

It’s February 6, 1960, about five in the afternoon. Darkness is falling. The Chevy Bel Airs and Ford Thunderbirds maneuvering their wide bodies off of Walnut Street onto Main are snapping on their headlights, making a sheen against the wet pavement. Saturday night is coming. Pippy diFalco is limping across Main Street. The weather is sleety, temperature in the high thirties.

Pippy is a small man wearing a big overcoat. He has an open face, puppyish eyes, shows lots of teeth when he smiles—kind of a goofy expression, which gives an impression of innocence. But that’s misleading. People say there was always something else going on. “Nice guy,” his onetime partner told me, “but not a nice guy.”

Pippy was what you would call a creature of habit. He left his home in the morning—he lived with his wife and infant son in an apartment in Morrellville, one of the oldest sections of town, a neighborhood of steelworkers’ houses and lots and lots of churches—and drove along the river. On his right rose a steep, wooded hill, at the top of which the town’s rich families had their homes. On his left he passed one of the four steel-mill plants that powered the town’s rise in the twentieth century. Today they are as silent as Greek ruins, but in Pippy’s time they incessantly poured smoke out of their high, skinny stacks. Every day the smoke put a fresh red-gray coat of dust on all the cars in town, which nobody minded wiping off because if the mills were churning, so was the town.

Johnstown had just peaked as a small industrial powerhouse. The population of 53,000 was already on the decline (it hit its apex of 67,000 in 1920), but good blue-collar jobs were still plentiful, and there were lots of managerial and professional types as well. Today the city is largely hollowed out, with neighborhoods of boarded-up houses and a population less than a third of what it once was. In Pippy’s time it rocked: shift workers crowding into the mill gates, the trolley cars full, housewives browsing the downtown storefronts.

He crossed the river and entered downtown. If he chose to follow Washington Street he would have driven past the public library and the big squat rectangular box of the Penn Traffic department store, its display windows showing lady mannequins stiff but elegant in sheath dresses. He found a place to park on Vine Street and limped down to the Acme supermarket on Market Street. He bought the same thing every day: a loaf of bread, a half pound of sliced bologna, a small pot of mustard. Then he headed up to Main Street, turned left, and came to a stop in front of the ticket booth of the Embassy Theater. Today the marquee said operation petticoat. The 11:45 a.m. show flickered into the mostly empty hall: Cary Grant and Tony Curtis, bright in Eastman Color, were officers on a navy sub who had to contend with “five nurses who just had to be squeezed in!” as the trailer screamed over a sexy flash from the horn section.

Sometime after the picture started, Pippy’s stomach would have been rumbling. His routine was to pull out a pocketknife, use it to spread the mustard, peel off a few slices of bologna and start eating his sandwich. He’d do the same thing later for an early dinner, watching shows in succession if it was a double bill, or, in this case, the same one over and over. Pippy wasn’t a movie buff; he was just killing time. Sometimes he had to leave the theater and walk around outside a bit, to stretch his legs, fill his lungs with air. But doing that meant he had to pay again to get back in, so he didn’t do it often; when it came to hoarding money, Pippy had great fortitude. Money was Pippy’s elixir. In his pocket as he sat in the Embassy was a thick roll of bills. Nobody knows exactly how much he carried that day, but the man who many people think killed him later that night told me with cheerful certainty that Pippy had “two pocketfuls of hundreds” on him. Pippy was famous for his cash rolls. People say he typically toted $3,000 in cash as he made his rounds, a pretty fabulous sum in 1960.

He left the theater for good around five p.m., ready to start his real day.

So here he was now, making his way across Main Street. He had taken shrapnel in the war, and ever since, despite wearing a corrective shoe, he’d had the limp, which made work not so easy, given what he did, but he did it anyway because it was what he knew, and because he relished it.

He was called Pippy from childhood: a nickname for Giuseppe, the Italian form of Joseph.

The sign on the building across the street said city cigar. Its name was both descriptive and deceptive. Cigars were nominally on offer, but its location, two doors from city hall, a handsome structure of rough-cut sandstone blocks on the corner of Main and Market, was crucial to its purpose.

My research takes us this far, brings me right to the front door of City Cigar, the headquarters of the mob back when it flourished in my hometown. But while City Cigar was an important stop on Pippy’s itinerary, I’m not entirely sure he went inside that night. Was he maybe avoiding the place just then?

If he did pull open that door, on his left would have been the shelves of cigars and cigarettes and a rack of newspapers: the Racing Form and the local daily, the Tribune-Democrat (the day’s headlines: “U.S. Answers Soviet Threat” . . . “Not Running, Johnson Says”). On the right side was a little lunch counter, run by Anthony Bongiovanni—Nino, everyone called him. Was Nino standing there, skinny guy with thick eyebrows and a shock of black hair, arms folded across his apron, looking him up and down? Nino wasn’t so fond of Pippy. Nino was thirty-one: eager, methodical, loyal. He was a cook, which was all he ever wanted to be, and this was a good gig, and he didn’t want anyone to mess it up. Pippy was forty-five, and he liked to be liked, but over the years he’d crossed a lot of people, including, lately, the two men who were both of their bosses.

One of those men might have been right there at the counter, where he liked to perch on a stool. His name was Joe Regino, but everyone called him Little Joe. You said it with respect. Little Joe ran the town. He was born fifty-three years earlier in southern Italy, emigrated with his parents, and grew up on the mean streets of Philadelphia. He got involved in the mafia before most Americans had heard the word. His first arrest, in 1928, was for armed robbery. Later he did time for counterfeiting. As the mob was expanding, he was offered control of Johnstown, with its population of hardworking, hardscrabble immigrants—German, Polish, Welsh, Irish, Italian. So he made his way across the state, married a local woman named Millie Shorto and befriended her brother, Russell or Russ, who became his closest ally. He made Johnstown his home and his world. He was a strikingly small, soft-spoken, unfailingly polite man who favored double-breasted suits and loyalty.

Little Joe was my great-uncle. I’m told I was around him somewhat when I was very young, but I don’t remember. What I’ve learned about him comes mostly from cross-referencing FBI files—which list “highway robbery” among his achievements, a crime I had thought went out with the stagecoach—with family reflections: “He had the sweetest disposition. . . . He was very quiet. . . . Uncle Joe helped everybody.”

Let’s assume that Pippy diFalco, after leaving the movie theater, had some brief interaction with Little Joe out front and then went in back. We’ll follow him, pushing open the swinging door. We’re met by smoke: a light cloud of it hovering in the center of the long room. The furniture consists of ten pool tables, one billiard table and several pinball machines. At this time of day you’d have maybe half the tables occupied: office workers, municipal employees from city hall, a few lawyers. All men, of course. Pool halls were as common as Laundromats in mid-twentieth-century America; Johnstown had half a dozen within a few blocks of City Cigar. But this one was a little different. The low rumble of the players’ chatter was spiced not only by the bright clack of ivory balls but by the constant chicka-chicka of the ticker-tape machine. It sat out right in the open, at the end of the counter that ran along the left side of the room, chucking out sports scores.

And here, in his natural environment, overseeing the landscape of green felt and blue smoke, invariably dressed in suit and tie and with a Lucky Strike in the corner of his mouth, I locate the object of my search. He was of medium height, bearish in build, and had a handsome, wide face and squinting, suspicious eyes. I’ve always thought he looked a bit like Babe Ruth. Russell Shorto went by Russ. “Hiya, Russ.” “Russ, we got a problem.” He was forty-six years old and at the height of his success—or rather, just past it. In fact, not long before, he had been cut out of the business by his brother-in-law. My grandfather was Little Joe’s second-in-command; the two men had built the mob franchise in town together; they were close. But Russ had a drinking problem, which had gotten so bad that Little Joe decided he had to let him go. Later, though, Joe had relented, given him a second chance. So Russ was now on a kind of probation. He needed to steady himself. He needed to make sure things went smoothly.

Despite his flaws, he had a talent for organization. Russ was largely responsible for having capitalized on the little steel town’s postwar boom by building an operation that generated what one knowledgeable person estimated at $40 million over the fifteen years since the war’s end (about $370 million today), a portion of which was sent off weekly to “the boys” in Pittsburgh. From there another portion supposedly was sent on to New York.

Gambling was the heart of Russ and Little Joe’s operation. Before there were legal, state-run lotteries, when even tossing a pair of dice against a wall and betting on the numbers that came up was considered immoral and a threat to public health, gambling was what the mob was all about. It was illegal—yet, in the glow and relative prosperity of the postwar era, people were crazy for the possibilities it offered, the giddy thrill of turning a bit of pocket money into sudden wealth. Gallup surveys in the 1950s showed that more than half the country’s population gambled on a regular basis. The mob—Russ and Little Joe—provided a service; a public utility, as many saw it.

In Johnstown, City Cigar was the center of things. The place itself was a hive of legitimate commercial activity: eight-ball was in its heyday, and there was a regular ebb and flow from the lunchtime rush to late at night.

The centerpiece of the Johnstown operation was something Russ created not long after the war, a cleverly named entity called the G.I. Bank, which sounded like a bedrock institution, something that supported the returning troops, but was simply a numbers game that half the town played. Like a lot of other local books around the country, the G.I. Bank took its winners from the closing numbers of the New York Stock Exchange. That made for a virtually tamper-proof system that encouraged bettors’ trust.

There were other games. “Tip seals,” a tear-off game much like today’s scratch-off lotteries, brought in millions in revenue. There were organized card games and craps games throughout the city, some of which had pots that got into the thousands of dollars.

Then there were the legitimate, or semi-legitimate, enterprises. They owned, wholly or with partners, diners, restaurants, pool halls, and bars.

I don’t imagine for a minute that the situation in Johnstown was unique. What Little Joe and Russ created in the period from the end of the Second World War to 1960 was mirrored in smallish cities across the country. New York and Chicago drew the attention of journalists and politicians, and therefore of the public, but the mob spread itself across the map like a corporation opening branch offices. In Pennsylvania, besides big operations in Pittsburgh and Philadelphia, there were Little Joes and Russes in Scranton, Reading, Braddock, New Kensington, Sharon, McKeesport, Penn Hills, Allentown, Wilkes-Barre, Greensburg, Monessen, Pittston, and Altoona. In 1957, when the FBI began to try to get a handle on the scope of things, it identified mob activity in such unlikely places as Anchorage, Alaska, and Butte, Montana. Bosses communicated, cooperated, and vied for power with one another in a continent-wide network.

In Johnstown, Russ oversaw much of the activity, but his particular area of focus was the sports book. It’s not like he was a dyed-in-the-wool fan (an old bookie set me straight on this: “Russ could give a fuck about sports”), but his way with numbers, his ability to set the odds, which required great precision, made him especially suited to sports-related gambling. He managed the bookies who took bets on baseball, football, basketball, horse-racing, and prizefights.

This is what brought Russ into regular contact with Pippy diFalco. Pippy booked sports. He had a regular route and regular customers, who knew where he would be at what time, and City Cigar was a part of that schedule. But lately Pippy had been light in his payments. Russ and Little Joe tolerated a certain amount of this. As Pippy’s onetime partner told me, “They knew that in a business full of cheats you gotta give guys some leeway.” They themselves were surely shortchanging the bosses in Pittsburgh, just as Pittsburgh was doing it to New York. Russ was something of a first-class cheat himself, especially with cards; he had probably gotten in his 10,000 hours of practice—false shuffles, second dealing, dealing from the bottom of the deck—before he was old enough to drive.

So: it took one to know one. Either Pippy had taken too much liberty this time or too many people had become aware of it. That’s why I think it’s possible that Pippy was avoiding City Cigar just then. Then again, if he had skipped his regular stop at the pool hall, wouldn’t that have sent a pretty nervy signal? He was just a guy, just a sap with a game leg and a stupid grin and a wad of bills in his pocket; he was in no position to give the mob the finger. So maybe he came in to offer an explanation of his situation.

If they talked, what did Russ say? What kind of threat might he have made? Russ carried a gun at all times, but I have no indication that he ever used it, and there didn’t seem to be a reason for anyone to fear for his life—not in Johnstown in 1960. “It was an innocent time,” more than one guy told me. But he and Little Joe knew how to use muscle. “If a bookie ran out on Little Joe, he’d call me,” one former enforcer told me from his nursing-home bed. “I’d go beat the guy up—get the money. Maybe I’d bring a .48 to scare him. Minor shit.”

So maybe we can go out on a limb and assume that Russ threatened Pippy that if he didn’t start making up for lost time, he would send somebody after him. One guy in particular they used for muscle—a guy called Rip, tall, lean and vicious, with blond hair and horn-rimmed glasses—would have been just the guy to put a healthy scare into Pippy. Once before, in a dispute over money, Rip had beat Pippy up, beat him real bad. Maybe, as that evening got under way, Pippy had the image of Rip in his mind.

Eventually, then, on this February evening in 1960, Pippy went off on his rounds. He probably headed east down Main Street, passing the one-square-block of Central Park on the left and Woolworth’s on the right, turned left at Clinton Street, past Coney Island Lunch, “world famous” (locally) for its chili dogs, and made his way to the Clinton Street Pool Room. It, too, was controlled by Little Joe and Russ. The same activities went on here, but whereas City Cigar was a leisure center favored by city officials, lawyers, and other elites, Clinton Street was a working man’s hangout. There was a counter where you placed bets, and spittoons at intervals. It was looser and louder than City Cigar.

Pippy presumably met clients that evening at the Clinton Street Pool Room. He passed a little time with Frank Filia, my mom’s cousin, the guy who got me started on this project during a four-hour chat session at his hangout, Panera Bread. By this time Frank had been working for the manager, Yank Croco, for nine years as a numbers runner and as counter man in the pool hall. Frank performed with the George Arcurio Orchestra on weekends and was building a name in town as a crooner. He was also an artist: in his spare time behind the betting counter he liked to make sketches of the regulars. When I asked, during a follow-up to our first Panera Bread session, what some of the people from his youth looked like, he picked up a stack of cocktail napkins and spontaneously re-created a few:

Click to view slideshow.Frank told me he had been feeling a little uneasy around Pippy around this time. Everyone, it seemed, knew that Pippy was welching on the mob. Or maybe that’s all hindsight.

Night came on. Nowadays if you venture to downtown Johnstown on a February evening you’ll find yourself in a rustbelt ghost town, but in 1960 the streets got lively even in winter. People headed to Hilda’s Tavern, where on this night the Harmony Tones were playing. The Gautier Club, a strip joint right above the Clinton Street Pool Room, was hosting its All-Star Floor Show and Orchestra, plus comedian Allen Drew. Back at City Cigar, the place filled up with men and smoke. It got rowdy; floor men stood ready to break up fights (one told me he had kept a broken cue stick on hand, and used it frequently). Even in bad weather, the opposite corner of the street outside, called Wolves’ Corner, was alive. Guys hung out there and whistled at broads, hoping for something to happen.

Midnight came. The sleet stopped; the streets glistened. At two o’clock the bars emptied. Then it got quiet.

Two doors down from City Cigar, the top floor of a three-story building became an illegal after-hours joint on weekends called the Recreation Club. It wasn’t much: a jukebox, two sofas, a little bar with its lineup of offerings: Kessler Whiskey, Walker’s Gin, Mogen David wine. Tacked to the wall was a board listing football and basketball scores. You had to be known to get in. It was seedy, smelling of old carpet and cheap wine, but it could get packed.

Pippy showed up here sometime after two, with a woman nobody had seen before. He was a married man with a two-year-old son at home, but everyone—including his wife, Barbara—knew he had a weakness for ladies. He didn’t have much going for him in terms of natural attractions, which was a likely explanation for the otherwise unnecessarily large wad of cash. People noted it that night, the flash of the bankroll, and the grin. Making an impression. Eventually he left, with the mystery woman on his arm.

___________________________________

-

When you think of the 19th Century English novelist and poet Thomas Hardy, you don’t necessarily think of suspense. Rather, he brings to mind the agricultural world of the southwestern counties of England, where most of his novels are set, and the harsh social circumstances (to put it mildly) of his characters. He’s renowned for his lyrical writing style, the romantic and pastoral elements of his books, and his commentary on the moral, social, philosophical and religious values of his time. But when I re-read one of my favourites, his 1891 novel Tess of the D’Urbervilles, it struck me that Hardy is also a master of suspense. And I felt compelled to start taking notes.

Perhaps this shouldn’t have come as a surprise. As the novelist David Lodge points out in his collection of fascinating articles, The Art of Fiction, Hardy’s earlier novel A Pair of Blue Eyes features a cliff-hanger in the most literal sense. The character Henry Knight slips while trying to retrieve his hat, and ends up clinging to a cliff face while the young woman he is secretly engaged to, Elfride, disappears to (we presume) find help. Hardy prolongs the suspense by describing in detail what Knight sees and thinks as he dangles there. At one point, he realises he is looking into the eyes of a fossilised creature in the rock: he stares the long-dead thing in the face as he wonders whether he himself is about to die. By the time Elfride returns, the reader is as desperate as Knight to know where she has been, what she will do, and whether he will survive.

This scene, as well as containing some very Victorian ruminations on geology, prehistory and the wildness of nature, is infused with tension, danger, bad omens and sinister imagery. These are used to clever effect throughout Tess of the D’Urbervilles, too—along with a range of other suspense devices, which I only fully noticed when I re-read it at the same time as I was writing the first draft of my novel, The Downstairs Neighbor.

Tess is an innocent young woman who, feeling responsible for her family’s poverty, takes a job in the grand house of a rich lady to whom she has been led to believe she is connected by name and ancestry. Tess is seduced and raped by the lady’s son, Alec D’Urberville, and becomes pregnant. Later, as she tries to put the trauma behind her, Tess falls in love with a gentleman farmer, Angel Clare, but their marriage falls apart when he learns of her past. The tension builds as Angel goes abroad and Alec closes in on Tess again, driving her towards the act that will seal her fate.

With my novelist’s hat on, I found myself wondering whether Hardy was a careful planner or an ardent editor. Because when you re-read Tess, you realise it’s peppered with chilling clues to Tess’s eventual ending. The early scene in which Tess accidentally causes the death of her family’s horse (a catalyst for the events that follow) is described with horrifying beauty: “The huge pool of blood in front of her was already assuming the iridescence of coagulation; and when the sun rose a hundred prismatic hues were reflected from it.” More than that, though, we’re told, “Tess regarded herself in the light of a murderess” – an early, subtle foreshadowing of what is to come. Later in the story, she passes a man in a field, painting Bible quotations onto a fence, including: “THOU SHALT NOT COMMIT—” The last word is omitted as the painter sees her and stops his work. It’s as if Hardy is pulling back from completing the clue, while knowing the reader can fill in the blank.

I once took a class on writing crime and suspense fiction, taught brilliantly by the author Lucie Whitehouse, and I remember one of her simple pieces of advice: ‘Unsettle your reader.’ And Hardy certainly does this; he heightens our unease to almost unbearable levels in the build-up to Tess’s life-changing encounter with Alec D’Urberville. Tess pricks her chin on the roses Alec gives her, endures a dangerous ride in his horse and cart, and eats blood-red strawberries straight from his hand, at his insistence. Even Tess’s mother, who hopes Alec will marry Tess and save their family, feels a shiver of misgiving as she sends her daughter off into his arms. How can the reader not feel the same?

After Tess leaves the D’Urberville mansion, Hardy employs another suspenseful device, this time structural. He leaps forward in time by a few months, but initially withholds information about what has happened in the interim. We re-approach Tess as if from a distance, observing her back in her home village, working in the fields—and then, on her break, a baby is brought to her for breastfeeding. It’s a jarring moment of realisation for the reader. A plot twist dropped into our laps while we’re still playing catch-up with the story.

Hardy does it again later in the novel, this time combining it with an agonising switch in perspective. Tess is now married to her true love, Angel Clare, but he has gone to Brazil and Alec D’Urberville has reappeared in her life. Hardy puts Tess in a situation of grave potential danger (and according to the great Patricia Highsmith, the essence of suspense fiction is “the threat of violent physical action and danger”), alone with Alec in the creepy D’Urberville family tomb. It’s a heart-stopping moment when Tess realises she isn’t alone; that one of the figures she thought was an entombed ancestor is actually the breathing shape of her pursuer. Abandoning her there at the end of the chapter, Hardy hops forward by a month, and into the perspective of a minor character. An old friend of Tess’s learns of Angel’s return to the country but has heard nothing of Tess. Next, we move into Angel’s perspective as he tries to track down his wife, and all the time we are wondering and worrying about our heroine who is off the page. We have more of an inkling about where she might be than Angel does, and every clue he uncovers during his search increases our fear for her.

These kind of storytelling devices are fascinating to me. Hardy makes very deliberate decisions about when to leave or enter different characters’ perspectives; when to close a chapter or a ‘Phase’ (part); when to cut quickly between events happening in parallel and when to make his reader wait. Many of these choices are made in the name of suspense, and to give maximum impact to his most important plot twists. And isn’t that exactly what the most page-turning thrillers do?

The climax of the book is, for me, his pièce de resistance. On first reading it, I was moved and horrified by the tragedy of it all, by the timing of Angel and Tess being reunited just too late. On re-reading it, though, I took greater notice of Hardy’s storytelling choices for ultimate effect. Not least, the genius move of narrating the moment Tess finally snaps from the point of view of an irrelevant character, the landlady of the lodgings in which she and Alec are staying. Through this stranger’s eyes—and literally through a keyhole—we see fragments of Tess and Alec’s final argument. Then, as the landlady returns downstairs (and after a few pages of prolonged suspense, complete with creaking floorboards and a glimpse of Tess running from the house), we get one of the most unforgettable moments of the book. The landlady sees a red stain spreading across the ceiling above her, with “the appearance of a gigantic ace of hearts.” This scene could be straight out of a Hitchcock movie. It’s somehow even more arresting than if we had seen Tess stab Alec first-hand.

Perhaps it was no wonder that Hardy’s climactic scene struck a chord with me at the time of my re-reading. My novel The Downstairs Neighbor, which I was then in the thick of writing, already included lots of scenes in which the residents of a shared building hear and see disturbing fragments of each other’s lives. Tess served as an unexpected reminder of how much potential there is to manipulate perspective and narrative in that kind of set-up. As I wrote subsequent drafts, I gave extra thought as to how I might crank up the unease in my fictional neighbourhood; make my readers worry about characters even when they were out of sight; or use ‘through-the-keyhole’ type moments to confuse and intrigue. You may spot one scene, in particular, which owes a debt to Hardy’s masterclass in suspense—though there is no blood seeping through the ceiling, not literally anyway.

*

-

When Putnam and the Ludlum Estates asked me to write The Treadstone Resurrection, all I knew was that it was a spinoff series that drilled deeper into the shadowy world of Operation Treadstone.

For those unfamiliar with the Ludlum Universe, Operation Treadstone was the covert CIA program that took Jason Bourne and turned him into a genetically modified assassin. A man capable of killing without hesitation or remorse. My contribution was to create a new hero. A protagonist who’d give readers a Bourne-like experience, but not a Bourne rip-off.

At first glance, it seemed pretty straightforward. In fact, as I began developing my protagonist, a former Treadstone operative named Adam Hayes, I told myself that not having Jason Bourne hanging around would make my life easier.

Turns out, that was total bullshit.

You see what I didn’t know at the time was that iconic characters like Jason Bourne cast long shadows. Really long shadows. And no matter what kind of literary sleight of hand I employed, it seemed that Adam Hayes just never measured up. Either he wasn’t smart enough or fast enough or cool enough. I wasn’t sure. But one thing was certain: Adam Hayes was being eclipsed by a man who wasn’t even in the damn book.

The first problem I encountered was straight out of Character Development 101. Mainly, an author needs to create a likeable protagonist. Now, I’m not saying your hero needs to be a choir boy or the kind of person who helps old ladies across the street, but they’ve got to have some sort of moral compass. Only problem was that removing a man’s moral compass was pretty much Operation Treadstone’s bread and butter.

The best approach was the one Ludlum took in The Bourne Identity, when Bourne developed amnesia after being shot in the head. I mean, how good is that? Not only can he not remember being a cold-blooded killer, but you as the reader are immediately sympathetic because the poor guy can’t even remember his name.

Thanks a lot, buddy.

I spent days trying to write my way out of this problem, and when that didn’t work; I went back to the source material. Then I spent another couple of days re-reading the books and re-watching the movies, desperately searching for a solution. When that didn’t work, I knew there was only one thing left to do—start drinking.

I was about halfway through the bottle and my thoughts were wandering around my brain like a dog off a leash when out of nowhere I remembered this article about Carl Jacobi, a German mathematician who believed the best way to clarify your thinking was to restate math problems in inverse form.

Now, I suck at math, so how you restate a math problem in reverse is beyond me, but I got the concept. All this time I’d been trying to out-think Robert Ludlum, create a protagonist who was stronger or smarter than Bourne, but this is not the way. I knew that now, and after jotting my findings on a Post-It Note, it was off to bed.

The next morning when I began writing it was with the idea that whatever Bourne was, Hayes would be the opposite. If Bourne couldn’t remember, then Hayes couldn’t forget. If Bourne was a loner, then Hayes would have a family, but perhaps most important of all, if Jason Bourne was a scalpel then my job was to make Adam Hayes a sledgehammer.

In the end both Jason Bourne and Robert Ludlum are icons for a reason. Mainly because when The Bourne Identity came out in 1980, books like that weren’t even popular. It wasn’t until after the books came out that audiences realized what they’d been missing. The same is true for the big screen. Don’t believe me? Fine, go back and watch The Bourne Identity and Die Another Day, both released in 2002. Then go watch Casino Royale the next Bond movie released in 2006 to see how the 007 franchise was rebranded to match the hyper-realism of the Bourne films.

When you’re done with your film comparison, go pick up a copy of The Treadstone Exile and find out why neither James Bond or Jason Bourne want to meet Adam Hayes in a dark alley.

*

-

The Man Who Didn’t Fly, first published in 1955, is a highly successful novel by an author of distinction whose crime writing career came to a sudden and rather mysterious end when she was at the peak of her powers.

The central puzzle in the story is unorthodox. A plane is engulfed in fire and crashes in the Irish Sea. The wreckage can’t be found. A pilot and three men were on board and their bodies are missing. But four passengers had arranged to go on the flight and none of them can be found. So who was the man who didn’t fly, and what has happened to him? This is such an original mystery that I don’t want to say much more about the plot, for fear of spoiling readers’ enjoyment.

The novel was a strong contender for the very first Gold Dagger Award for best novel of the year given by the Crime Writers’ Association (in those early days of the CWA, the award was known as the Crossed Red Herring Award). In the event, it was pipped by The Little Walls, written by Winston (Poldark) Graham, while Ngaio Marsh’s Scales of Justice and Lee Howard’s Blind Date were also shortlisted. A couple of years later, the novel was again a runner-up, this time to Charlotte Armstrong’s A Dram of Poison, for the Mystery Writers of America’s Edgar Award for best novel.

In other words, this was the first book to be shortlisted for the premier crime novel awards in both Britain and the U.S. Julian Symons included the novel in his The Hundred Best Crime Stories, a list compiled in 1958 for the Sunday Times and also published separately, in which he described Bennett as “the wittiest of recent crime novelists, but in other respects the most unpredictable.” As if that were not enough of an achievement, the story was adapted for television in America in 1958, with a cast including the young William Shatner, later to find fame as Captain Kirk in Star Trek, trying out his version of a British accent. Given the success of the book on both sides of the Atlantic, it’s sobering to consider that it has been out of print for a quarter of a century.

Margot Miller was born in Lenzie, Scotland, in 1912, and at the age of fifteen, she emigrated with her family to Australia. In the early 1930s, she spent some time in New Zealand, working on a sheep farm. Much later, she used her first-hand experience of the massive 1931 Hawke’s Bay earthquake for her mainstream novel That Summer’s Earthquake, set on a sheep farm and published in 1964. She took a job as a copywriter in Sydney, Australia, and moved back to London at the age of twenty-three, where she continued to work in advertising. During the Spanish Civil War, she went to Spain as part of the first British Medical Unit. There she met Richard Bennett, her future husband, who shared her left-wing political sympathies. The Bennetts had four children together.

Margot’s first novel, Time to Change Hats, was published in June 1945 but very clearly set in wartime, with references to the Home Guard and a rural English village invaded by evacuees. She and her two older children had themselves been evacuated, to a village in Cornwall. Her publishers described the book as “a story of drink, a cow, and the fine art of murder.” After the long years of war, they promised readers: “If you are tired of murder in the raw, here is murder in a comedy.” Bennett set the tone in her dedication (“To My Creditors”) as well as in the first line: “It is difficult to become a private detective; the only recognized way is to be a friend of the corpse.”

The narrator is John Davies, who finds his friends disobliging until Della Mortimer responds with a note saying: “I have not been murdered, but may be. A woman called Death has been leaving visiting cards.” This makes for a pleasing start to a story, and the book was well received in Britain and the U.S., although Bennett later commented, with some justice, that her attempt to “try the novelty of combining comedy with the obligatory murder” resulted in the book being too long.

Davies returned in Away Went the Little Fish, published the following year. This mystery displayed Bennett’s developing talent, but she promptly abandoned Davies, and she did not produce another crime novel for another six years. The Widow of Bath was undoubtedly worth the wait. Her skills as a crime writer had matured in the interim and the story blended first-rate characterization with a strong mystery puzzle. Bennett was, like all good writers, self-critical, and she observed that it “had an entirely plausible and novel plot, but it was low on comedy and had too many twists.” This success was followed by Farewell Crown and Good-Bye King, a book written with the accomplishment that marks all her fiction, albeit pivoting on a plot twist that is pleasing but perhaps too easily guessed.

Bennett felt that her last two mystery novels, this one and Someone from the Past were her best. After her near-miss with The Man Who Didn’t Fly, in 1958 she succeeded in winning the Crossed Red Herring Award (it was renamed the Gold Dagger in 1960) with Someone from the Past. The next year, 1959, she was also elected to membership of the Detection Club. She had reached the pinnacle of her profession. But that, as far as crime writing was concerned, was it. Astonishingly, she never published another mystery novel, an extreme example of a crime writer going out at the top.

She had reached the pinnacle of her profession. But that, as far as crime writing was concerned, was it.Instead, she concentrated mainly on writing for film and television. Women Screenwriters: an International Guide describes her as a writer of B-movies, only two of which were actually produced, the comedies The Crowning Touch and The Man Who Liked Funerals. She adapted The Widow of Bath for television and wrote scripts for popular series such as the medical soap opera Emergency Ward 10 and Maigret. Her last known writing credits were in 1968. She wrote scripts for Honey Lane, a cockney forerunner of EastEnders, and a science fiction novel, The Furious Masters, which made less impact than her previous venture into sci-fi, The Long Way Back, published fourteen years earlier.

Why did this gifted and versatile author, who lived until 1980, first give up crime writing, and then apparently stop writing for publication altogether in her mid-fifties? It’s a puzzle to rival anything in her books, and I’m very grateful to Veronica Maughan for casting light on Bennett’s life and career. It seems that Bennett found screenwriting more lucrative than producing novels at a time when she was also raising a family, and that in the 1960s she became increasingly committed to political campaigning. She was closely associated with CND and Amnesty International and in 1964 published The Intelligent Woman’s Guide to Atomic Radiation, a book which (like her forays into science fiction) reflected her anxieties about nuclear proliferation.

This volume includes a bonus for Bennett fans in the form of a little-known short story, “No Bath for the Browns,” which first appeared in Lilliput in November 1945 and then in the U.S. in The Mysterious Traveler seven years later; I’m indebted to Jamie Sturgeon for supplying me with this information and a copy of the story.

It was thanks to Julian Symons’s Bloody Murder that I first became aware of The Man Who Didn’t Fly, and when I finally tracked a copy down in a library, I enjoyed reading it. Some years later, I was invited to write an introduction to a reprint published in 1993 by Chivers Press in conjunction with the CWA, and again the story entertained me. So this is, strangely, the second time I’ve written an introduction for a reprint of this novel—although I’ve tried to avoid repeating myself! My hope is that other readers will share my enthusiasm for an author who, despite a regrettably slender output, ranks high among British crime novelists of the post-war era.

-

The headline pretty much says it all—after three decades of reviewing an incredibly wide variety of crime novels, Marilyn Stasio has retired from writing the New York Times Book Review’s crime column, although she will still contribute occasional reviews to the newspaper.

Sarah Weinman, author of The Real Lolita and frequent contributor to national publications as well as editor of a number of landmark anthologies, is the natural choice to succeed Stasio—Pamela Paul of the NYT calls her the “the most obvious suspect” and we couldn’t agree more. We won’t be seeing her Crime Lady newsletter as much anymore, but we’re looking forward to reading her column—the first one’s up today!

Weinman continues a long tradition of New York Times crime columnists stretching back to the original tastemaker, Anthony Boucher, for whom the mystery world’s largest convention is named.

Check out some of Sarah Weinman’s columns for CrimeReads here.

-

I love the show Moonlighting, but everyone loves Moonlighting. To see Moonlighting is, in fact, to love it, though if you didn’t watch it when it aired, from 1985 to 1989 on ABC, there’s a chance you may never have seen it. None of its five seasons are available in digital versions, for purchase or subscription streaming. The handful of DVD editions produced in the early 2000s are out of print. The only way to watch it now is via a mélange of YouTube clips, or to get your hands on those rare physical copies (which is what I did, via many stressful eBay auctions, tortured soul that I am). The eventual obscurity of this show is, as far as I’m concerned, a crisis. Moonlighting, an hour-long mystery series which ran on Tuesday nights, is about the unlikely pairing of a tough, Type-A former model (played by Cybill Shepherd) and a scrappy, motormouth PI (a then-unknown Bruce Willis), who team up to run a detective agency. It is endlessly entertaining. It is full of energy and pathos, of lust and tension, of joy and laughter—a firecracker of a program whose antics feel not only amusing, but also, in a way, moving. Watching it, you can’t help but find it special.

I confess that I didn’t watch Moonlighting when it aired, not having been born until a few years after it ended. But Moonlighting is a timeless, nostalgic show—initially owing much of its personality to Golden Age Hollywood’s screwball comedies and noirs, plus assorted odds and ends from other film and television genres. As the seasons went on, Moonlighting began to experiment with form and aesthetics. There were referential acknowledgements of the camera, extended dance sequences, and one Zeffirelli-esque Shakespearean episode spoken (almost) entirely in iambic pentameter. Moonlighting gave Bruce Willis his start. It gave Cybill Shepherd her comeback. There were glittering evening gowns, big-budget and high-flying climaxes, and zinging banter slung so deftly that you might have forgotten you weren’t watching Rosalind Russell and Cary Grant. There was chemistry so palpable and powerful it’s a wonder why every TV set in America didn’t burst into flames every week.

The story of Moonlighting itself—that is, making Moonlighting—is no less fiery. There were real-life feuds, backstage fireworks, and an always-behind production schedule that promised more episodes than were ever delivered. According to crew members, sometimes scenes would be filmed for an episode that needed to air that night. One crew member remembers handing in a full episode to the studio a half hour before its air time. In the show’s final seasons, its two lead actors became less involved; Cybill Shepherd because she was pregnant, and Bruce Willis because he had made it big. After becoming the (singing) spokesperson for Seagrams Wine Coolers, Willis became an action star in 1988’s surprise hit Die Hard, and thus became extremely unavailable for Moonlighting commitments. To sustain itself, the show began to spotlight its minor characters, two agency employees named Agnes DiPesto (Allyce Beasley) and Herbert Viola (Curtis Armstrong), who, while adorable and charming, didn’t supply the romantic voltage that drew viewers to the show in the first place. But by the time it was cancelled in 1989, after the behind-the-scenes problems had completely engulfed the actual process of making it, it had still accomplished something vanguard, and brought something new and wonderful to television.

* * *

It’s impossible to say all the ways in which Moonlighting influenced television that came after it. Its wacky breaking-the-fourth wall, mile-a-minute jokes, throwaway references that not all audience members might even understand place it in a lineage of television’s smartest, most sophisticated situation comedies. And its particular, zany take on the “lighthearted detective show” gambit was new, too—whenever I watch a show like Psych, I am overcome by the debt owed to Moonlighting. But Moonlighting’s impact was also extremely personal. One of these days I’ll launch an essay contest, a “what Moonlighting means to me” sort of deal. It made an enormous impact. The television critic Howard Rosenberg, who had panned the show upon its release, wrote a correction a few weeks later to apologize for not having understood Moonlighting and to confirm that he had since seen the light. After its startling first season, it had become such an enormous sensation that (according to people who were alive in the 80s) Moonlighting became the ubiquitous conversation topic on Wednesday mornings at work. Two years after it aired, sixty million viewers tuned in to watch the protagonists finally hook up, in a passionate (edgy for prime-time) sex-scene that involved destroying every nearby prop. (Anyone who wants to read about this, more in-depth, should pre-order Scott Ryan’s official book on the series, which is due out in June 2021.)

It’s funny, because the circumstances in which I first saw Moonlighting (on YouTube, in 2014, after my mom had recommended it) were almost relatively meaningless to me. I watched it almost in a vacuum—devoid of any advertisements, hype, the strange (plot-spoiling) TV trailers that were ubiquitous on ABC before its premiere on March 3rd. And yet I was entranced. Not that I ever mind watching something that is a relic of its own era of production, but I didn’t need any context to connect with what I was watching. Moonlighting didn’t feel like a product of the 80s so much as an accumulation of the entire entertainment world that came before it—a world that I already loved.

Moonlighting is about two people, two complete opposites, with absolutely no romantic history, who nonetheless build a rich romantic history for themselves—one scrapped together from a long archive of mainstream pop culture.Moonlighting is about two people, two complete opposites, with absolutely no romantic history, who nonetheless build a rich romantic history for themselves—one scrapped together from a long archive of mainstream pop culture. Our protagonists, Maddie Hayes and David Addison, are “moonlighting” in that neither one of them has any (figurative) business in literally operating a detective business, but they are also “moonlighting” in a more abstract sense, slipping in and out of various love stories… borrowing the best elements from a great syllabus of romances, from William Shakespeare to Howard Hawks to Raymond Chandler, giving themselves the opportunity to enjoy falling in love over and over, in all these many styles and moods.

So often, Moonlighting is a string of fantasies. The show dreamily wonders what its characters would look like—how they would spar, how the sparks would fly—in other aesthetics, and so blinks them there. No greater example of this occurred than when writers Debra Frank and Carl Sautter wrote them an episode shot entirely on real black-and-white film stock entitled “The Dream Sequence Always Rings Twice.” The show’s creator Glenn Gordon Caron had been informed by the studio to record it in color and have the picture altered later, but he insisted it needed to be recorded on the genuine material from the era they were capturing. The episode, which you can watch in full on YouTube, is marvelously grainy, with dipping, swooping shadows, by cinematographer Gerald Perry Finnerman. Looking at it, it’s nearly impossible to tell that it was made forty-five years after Humphrey Bogart played Sam Spade.

And, emphasizing its investment in film history is its best cameo: the episode is presented to the audience with an introduction from an elderly Orson Welles, who informs the audience (in color) that their screens are going to play the episode in black-and-white, and assures them that the “monochromic, monophonic” transformation they will witness twelve minutes into the broadcast is not a malfunction on the part of their sets. The writing team noted that when Welles recorded his scene, the stage had filled with crew members, quietly, respectfully watching the master at work. Welles would die exactly one week later. It was the last thing he made that would air during his lifetime. It was his last performance.

“The Dream Sequence Always Rings Twice” isn’t really a mystery (it’s two dream sequences, one for Maddie and one for David, that imagine outcomes of a cold case from 1946). That’s fine, because Moonlighting isn’t really a detective show, anyway. Yes, there are cases, but just enough. The detective agency is the pretense, and frequently, this shows. Its creator, the twenty-six-year-old Caron, had been given an opportunity to develop some pilots for ABC, and Moonlighting was his third. He had been specifically instructed to write a “boy-girl detective show,” a rote genre which Caron despised. He had written some episodes of Remington Steele (a more traditional mystery show that ran from 1982-1987 and starred a young Pierce Brosnan as a thief who pretends to be a detective to work with a cool lady PI, I KNOW), but didn’t have much experience with the genre. Moreover, he had little interest in writing something that felt so formulaic. But the more he protested, the more leeway the studio gave him. He would later say (in the interview on one of my Moonlighting DVDs) that Moonlighting appeared to break so many rules (of the detective show format, of television in general) because he had never actually known “what the rules were.”

Make no mistake, Moonlighting is about the central relationship between Maddie and David, and the precise nature of this relationship is ultimately the central mystery. When will they realize they are soulmates? Do they already know? From the moment the two meet, their personalities chafe and clash. The theme song, with lyrics written and vocals provided by Al Jarreau, refers to them as “moon” and “sun”—two strong, elemental antipodes cosmically, perhaps even magnetically drawn to one another (I don’t remember eighth grade earth science, bear with me). Maddie is a no-nonsense former model (famous for being the “Blue Moon Shampoo girl”) whose business managers have just (legally) robbed her of her life savings. But she discovers that she owns several businesses (including a detective agency) as tax write-offs. She shuts them down, but when she arrives at the last one, the City of Angels Detective Agency, she can’t manage to do it. That’s because its proprietor, the loud, constantly-quipping wiseass gumshoe David Addison begs her to go into business with him, to turn the company around. A series of misadventures, which leads them to a treasure hunt for hidden Nazi diamonds, ultimately convinces the reluctant Maddie of their compatibility, or at least viability. It’s clear (to everyone) that they, fire and ice, will fall passionately in love. The fun is watching the ardor stall for as long as possible.

Moonlighting is about the central relationship between Maddie and David, and the precise nature of this relationship is ultimately the central mystery.Cybill Shepherd notes, in an interview, that this tension was maintained because she and Bruce Willis were “never lovers” in real life, though by all accounts, mutual attraction was there. Caron had to promise the studio that the relationship would not become romantic right off the bat, in the two-hour pilot, mostly because the executives (who were skeptical about the ever-so-slightly-crass Willis) could not believe that he would ever conceivably be the object of affection for someone as polished as Shepherd. But Caron thought the tension between a sloppier huckster of a man and an elegant woman was essential for the gambit—if he had been making a film version, Caron said, he would have cast Bill Murray and Jessica Lange.

Caron was sure that Shepherd and Willis would have sparkling chemistry, despite not actually having seen them act together (Shepherd, who had signed onto the part after seeing a mere half a script, was terrified that she might be replaced if she did a screen test, so she refused—though she needn’t have worried, because Caron wrote the part with her in mind). Caron’s intuition was on the money: they were a perfect match. (Willis jokes that the real screen test was in the elevator ride on the first day of shooting, where he met Shepherd in person and he wouldn’t stop flirting with her.) Eventually, their mutual interest turned to competitiveness and ire; they wound up fighting before every single (scripted) fight scene. But their friction only seemed to fuel their onscreen dynamic. Back before production had even begun, when Shepherd had read Caron’s script, she excitedly told him that he had inadvertently written “a Hawksian comedy,” and obligatorily within that, a kind of glamorous, witty female leading role bursting with vim and fizzing with repartee. An ardent fan of screwball comedies, she had always dreamed of a part like this.

Maddie Hayes is fierce; she suffers no fools, and this is rotten luck for David most of the time. Maddie’s contribution to the comedy comes from her transformation—her acceptance of and eventual participation in the cockamamie circumstances in which she finds herself and which are often David’s fault—as much as her conviction. She bosses David around because she is serious, but she isn’t so serious that she winds up doing all the (emotional, or literal) labor. David, who appears at times to be an immature clod, is hopelessly clever and relentlessly brave. He’ll jump in the path of a shooter, or leap on top of a moving train. Maddie is brave, too—though she’s more calculating than her partner. In the pilot episode, she scales a level of Los Angeles’s Empire clock tower in a pencil skirt and heels, as calmly as if she’s ascending a staircase at a gala, wearing one of her fabulous gowns.

It’s noteworthy, also, how both of these actors become so funny in their comic parts—Shepherd for her glowering glances and cranky intonations, Bruce Willis for his sound effects and willingness to loudly burst into song (or trill into a harmonica) at a moment’s notice. (Because of all his riveting shenanigans in Moonlighting, I find that Willis’s subsequent, totalizing career as an action star is a bit of a shame, because it has suppressed the roles he might have taken that allow him to be a total ham, and he’s so, so good at that). But, as I’ve said, the funniest part of the show is the rapier-raillery, a volley of puns and cracks so crackling that you’ll rewind your Moonlighting DVD three times to catch everything (or record it with your iPhone and text it to all your group chats, ahem).

Moonlighting’s charms superseded the familiar “battle of the sexes” framework it naturally employed. Though Maddie and David were obviously in love the whole time, the forestalling of their relationship led to them establishing a dependable, beautiful friendship. They were partners, neither with the professional upper-hand nor greater industrial know-how. They were resourceful, kooky, ride-or-die friends. Best friends.

Crew members—writers and other artists—noted that the atmosphere on the show was especially friendly and loving. In part because of Caron’s freewheeling showrunning, which allowed writers to have fun with their scripts and even make obscure jests that audience members might not understand, it became Moonlighting’s ethos that the team wasn’t writing a show to please anyone, least of all network executives—they were doing it to make the kind of show they, themselves, wanted to watch. Caron wound up going to bat for his strange (and often big-budget) production countless times, promising skeptical executives that whatever unconventional turn the show would take, would wind up enormously successful.

Key to the soul of Moonlighting is the knowledge that it is a pastiche,that it is meta. But its reflexivity isn’t merely a gag, it reflects a particular investment. In a show that is so much about teamwork, friendship, love (and also, conversely, “winging it” while shooting for the stars), it became increasingly meaningful to illuminate the relationship between the performers and the crew—that everyone on set was “in” on a joke together, that behind the effortless, dueling bon mots were teams of laughing writers. No episode emphasizes this more than Season Two’s Christmas episode, in which the camera pulls away from David and Maddie to reveal an entire soundstage packed with staffers.

Crew members had received last-minute notice to come to the studio that day, and bring their spouses and children, to make an ensemble appearance. As the camera pulls out away from the two stars, revealing the village it took to make Moonlighting possible, everyone starts to sing, together. The song is the carol “Noel.” Actress Allyce Beasley, who plays the agency’s rhyming secretary Agnes, says of this moment that “there was a feeling in the air you could almost touch,” for its being “so tender and so sweet.” The show’s theme song promises a unification of “moonlighting strangers who met on the way,” and here was a room full of them, once unknown to one another, and now a passionate group of friends. Besides that this scene was formally innovative, it was also sentimental. It was loving. Indeed, as other crew members noted, “every day” making Moonlighting “was special.”

I wish so badly that Moonlighting were accessible via some sort of streaming platform (really, ABC, we are in a *pandemic*… now is the time to do it… it will make so many people furiously gleeful, I promise). I don’t often write essays so bereft of thesis statements—rather, essays in which my thesis statement is really just an adulation or a recommendation. But it seems silly to try to dig far into Moonlight analytically when no one else can feasibly watch it. Instead, this essay serves to ask you to remember it, to try to revisit it, or to do what you can to meet it for the first time. Moonlighting is a show about loving movies. It is a show about loving form, and genre, and history. It is a show, such a niche show, that was made to simply be fun, to make fun with friends and the people you come to love. And for all these reasons, it is nothing short of magic.

-

The Valentine’s Day love note from a secret admirer has an evil twin—the “vinegar valentine” from a hidden hater. When mass-produced valentines replaced handmade ones in the Victorian era, satirical valentines were as available as sentimental ones. Vinegar valentines, ancestors of poison pen letters and trolls’ tweets, ridiculed their recipients and sometimes drove them to suicide or assault.

Sending cards with poems of love and friendship to mark Valentine’s Day became common in the 18th century. This practice grew out of an earlier tradition of gift-exchange between lovers on that day. In pre-Victorian England, valentines were handmade and resembled today’s cards in their depiction of flowers or other symbols of love along with sentimental verses. To avoid triteness, poetically-challenged men and women had to resort to annual pamphlets like Every Lady’s Own Valentine Writer, in Prose and Verse for the Year 1794.

Nineteenth century advances in printing and paper production took away the burden of composition, brought inexpensive cards to the market, and spread the custom of sending paper tokens of affection. After 1840, when Great Britain established the Uniform Penny Post system, sending cards became cheap, fast, and anonymous. That, along with the rise in literacy, pushed the annual number of Valentine’s Day cards sent in Great Britain from an estimated 200,000 in the 1820s to nearly eight times that many in the 1870s.

Some of that growth came from card vendors’ introduction of mocking valentines, which could go to neighbors, relatives, and colleagues in all classes and walks of life. Those cards were also available across the Atlantic. The 1847 catalog of A. S. Jordan, an American importer of British valentines, listed cards not only in such traditional categories as Romantic, Courting, and Matrimonial but also Caricature, Spiteful, Lampooning, and even Suicidal. Many people couldn’t resist putting curare on Cupid’s arrow. According to estimates, half of all valentines sent in the United States by the mid-19th century were the spiteful kind. Usually, they were printed on a single side of flimsy paper, not on folded card stock. It was cheaper to insult than to praise.

Vinegar valentines married humorous images to caustic sentiments. The typical format was a caricature of the recipient and a short verse at the bottom. Sometimes women sent anti-valentines to men who were pursuing them. In one, a woman is shown holding a huge lemon inscribed with “To my Valentine.” She extends the lemon to a miniscule man in the lower corner of the card. The verse reads: Tis a lemon that I hand you / And bid you now “skidoo” / Because I love another— / There is no chance for you! Likewise men sent vinegar valentines to damsels who’d dared turn them down or to women they were throwing over.

Even in the absence of a personal relationship, women received valentines mocking them for behavior that would drive away men. Cards derided women for frowning and also for smiling too much. A card with a finely dressed woman in an elaborate hat and a skirt made of peacock feathers reads: Proud beauty you’d best lay aside, / Your nonsense and your peacock pride, / Or none will have the pluck to say, / “Fair lady will you name the day.”

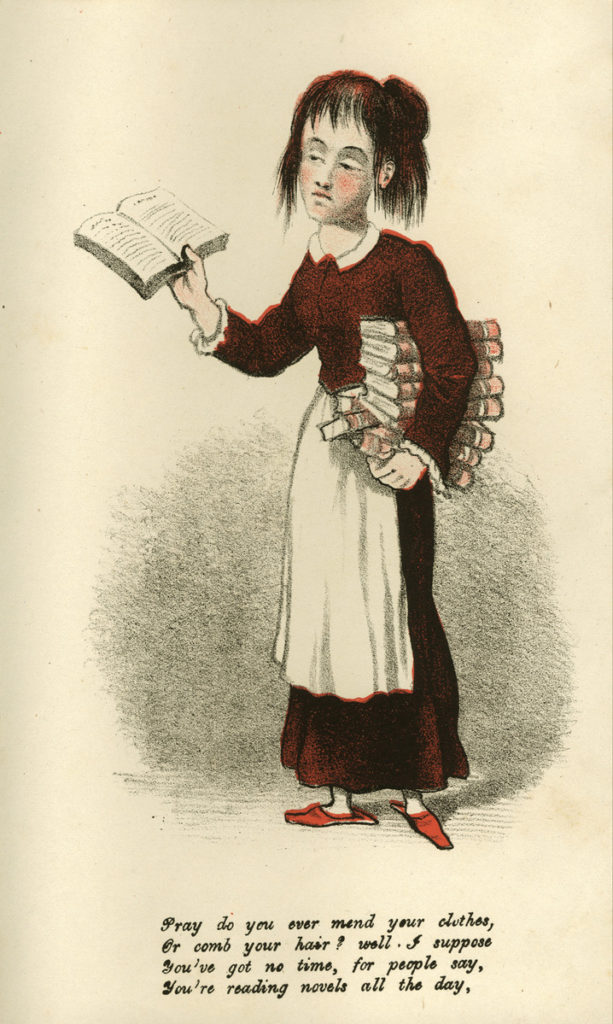

Other valentines condemned women for not dressing well enough. An illustration of an unkempt woman with a stack of books under one arm is accompanied by these words: Pray do you ever mend your clothes / Or comb your hair? Well, I suppose / You’ve got no time, for people say / You’re reading novels all the day.

Phrases like “people say” and “everyone knows” often appear in the mocking valentines. The sender thereby proclaims he is speaking on behalf of the larger community, not out of his own malice. As the women’s suffrage movement grew, so did the number of valentines lampooning women who fought for the right to vote. One of these reads: The vote from me you will not get / I don’t want a preaching suffragette.

Men were also the butt of vinegar valentines. They were criticized for drunkenness, vanity, stinginess, and stupidity. Some vinegar valentines didn’t even bother with poetry, but chided in prose: Everyone thinks you an ignorant lout or Don’t borrow money from your friends. Pitch in and earn it for yourself.

Cruel valentines poked fun at people’s physical characteristics or misfortunes, including their age, excessive weight, or widowed status. The most malicious cards suggested suicide to the recipient. The image on one of them depicts an oncoming train with the verse: Oh miserable lonely wretch! / Despised by all who know you; / Haste, haste, your days to end—this sketch / The quickest way will show you!

Vinegar Valentine’s card, c1875.

Vinegar Valentine’s card, c1875.

Though many sentimental valentines from the 19th century have survived, offensive valentines are rare, presumably because offended recipients burned or trashed them. Some had even stronger reactions to them. In 1847 a New York City woman overdosed on laudanum after receiving a nasty valentine from a man who’d led her to believe she was his love interest. In 1885 a London evening newspaper, the Pall Mall Gazette, reported that a man was charged with attempting to murder his wife: “The pair lived apart, and on St. Valentine’s Day she sent him an offensive valentine. In his anger he purchased a revolver, and meeting his wife last night shot her in the neck. The woman lies in the hospital in a critical condition.” Reports appeared in newspapers of fighting and physical assaults resulting from a vinegar valentine’s “scurrilous lampoons” (Dundee Courier and Argus 1877).

Because of public revulsion, these valentines became less common in the latter part of the century in England. Their popularity declined a few decades later in the United States, about the time when the poison pen letter became the chosen instrument of verbal abuse. Instead of the stock verses of the valentine, the letter allowed for customized venom. In another CrimeReads article, Curtis Evans explores the rash of poison pen letters during this period: The Poison Pen Letter: The Early 20th Century’s Strangest Crime Wave.

Fast forward to our century, when the cyberbully and the troll personify the spirit behind vinegar valentines. Hate springs eternal.

Happy Valentine’s Day!

***

-

As we all know, the worst thing to happen to mainstream American cinema in the 21st century was the near-total abandonment of that most compelling and enigmatic of subgenres: the erotic thriller.

While there have been a few notable additions to the canon over the past two decades (In the Cut, Unfaithful, Gone Girl, When the Bough Breaks…em… The Boy Next Door) the sweaty heyday of the erotic thriller has been over for some time now. Its Golden Age was actually quite a lengthy period, beginning (I would argue) in earnest in 1981 with Bob Rafelson’s remake of The Postman Always Rings Twice and ending in 1996 with the Wachowskis’ Bound. (I will also accept 1998’s Wild Things as an end point, for those of you who prefer a messier climax to your cinematic eras).