-

Posts

4,576 -

Joined

-

Last visited

Posts posted by Admin_99

-

-

Earlier this month, we were excited to learn that Sisters in Crime has launched a new program to support emerging LGBTQIA+ authors! Submissions are now open for the inaugural Pride Award for Emerging LGBTQIA+ Crime Writers, which will provide a $2,000 grant to an emerging crime fiction writer at the beginning of their career who identifies as LGBTQIA+. There is no cost to submit. This is the first year for the Pride Award, which has been created as the legacy project from past Sisters in Crime president Sherry Harris.

We caught up with this year’s judges, John Copenhaver, Cheryl Head, and Kristen Lepionka, to find out more about the new program, and to discuss the state of crime writing for the LGBTQIA+ community. As the following conversation shows, the world’s a lot better now for queer crime writers than it used to be, but there’s still a whole lot of work to be done.

John Copenhaver’s historical crime novel, Dodging and Burning, won the 2019 Macavity Award for Best First Mystery Novel and garnered Anthony, Strand Critics, Barry, and Lambda Award nominations. His second novel, The Savage Kind, will be published in October 2021. He writes a crime fiction review column for Lambda called “Blacklight,” and cohosts on the House of Mystery Radio Show. He lives in Richmond, VA. www.jcopenhaver.com

Cheryl Head’s debut book, Long Way Home: A World War II Novel, was shortlisted for the 2017 Next Generation Indie Book Awards in the African-American Fiction, and Historical Fiction categories. Head writes the award-winning, Charlie Mack Motown Mysteries whose female PI protagonist is queer and black. The series is included in the Detroit Public Library’s African-American Books List. Head is a member of the national board of Bouchercon. In 2019, she was named to the Hall of Fame of the Saints and Sinners Literary Festival. Visit Cheryl online at cherylhead.com

Kristen Lepionka is the Shamus and Goldie Award-winning author of the Roxane Weary mystery series. Her books have also been nominated for Anthony and Macavity Awards, and she is a co-founder of the feminist podcast Unlikeable Female Characters. Find her on social media @kmlwrites or at www.kristenlepionka.com.

_______________

CR: Why is the SinC Pride Award important to the LGBTQIA+ community and how can it help writers?

Cheryl Head: For a writer starting out in their career, every affirmation that you are on the right track can keep your spirits and ego high and push you to the next level of accomplishment. I believe this award will have that kind of value.

Kristen Lepionka: There are a lot of different grants and awards in the writing world, and the SinC Pride Award is the first I’m aware of that is specifically for queer crime writers, and it’s so important to have that spotlight on our corner of the genre. And more than that, it’s an opportunity to support an emerging writer at a critical stage in the development of their career, which can make all the difference in the world to someone who is just starting out.

John Copenhaver: The award will help up and coming queer authors find mentorship and some financial support. Most importantly, though, is that it’s a powerful way for Sisters in Crime to declare itself an ally organization and take action to demonstrate that allyship.

CR: Why are you excited to judge this event?

Kristen Lepionka: I want to read all the best new queer manuscripts! But also, I’m thrilled to be a part of something that has the potential to positively impact someone else like me. Knowing what we know about the publishing industry and the limited number of #ownvoices books that get traditionally published, I know I’m fortunate and I want to pay that forward however I can. Plus, John and Cheryl are awesome, and I’m really looking forward to discussing the entries with them.

Cheryl Head: I’m always ready to help another writer. Also it’s inspiring for me to learn of other queer writers working in my field. This award, in particular, has so many valuable elements: A cash award for career development activities, membership in the incredibly supportive Sisters in Crime community, and a manuscript critique. That’s a win-win-win.

John Copenhaver: It’s exciting to be able to read and support LGBTQ+ writers in the mystery/thriller genre. I’ve been reviewing crime fiction for years. I know that there’s so much superb writing out there that gets overlooked because many publishers think that queer fiction—particularly if it’s genre—is too niche for a broader audience. They believe only LGBTQ+ people want to read about LGBTQ+ people. I don’t think that’s true. Younger readers are reading across difference. The readers of the future don’t just want to read characters that mirror themselves; they want to read great stories about people who are different than they are. If I can play some role in building the bridge to a broader audience for an up-and-coming writer, I’m all for it.

CR: What has your writing experience taught you about how this award could be helpful?

John Copenhaver: Representation is key. Awards that highlight traditionally underrepresented writers, like the Pride Award or the Eleanor Taylor Bland Award, in organizations that aren’t specific to those writers, are sending a compelling message: We want you. A broader audience wants you. Welcome!

Cheryl Head: This business of writing is certainly about talent, but it’s also about getting the attention of readers and reviewers and agents and peers. The Pride Award will put an emerging writer’s name on the radar of so many influencers in our writing community.

Kristen Lepionka: When you are just starting out, you don’t know what you don’t know, let alone who to ask to find out. The community aspect of SinC is such an important element of this.

CR: What do you think is the biggest obstacle when it comes to diversifying mystery and crime fiction?

Cheryl Head: Getting readers to take a chance on a new author. Mystery crime read fans-and I count myself among them-know what they like. They can be very loyal to a few authors and very habitual about what they buy. What I’d love to see is more readers stepping out of their comfort zones to try works in new styles and from new voices. I love noir. But I read broadly, and I know that noir is not just a white, male, P.I. in a fedora. It’s a state of mind; a defining mood; stories both bleak and self-reliant.

“[N]oir is not just a white, male, P.I. in a fedora. It’s a state of mind; a defining mood; stories both bleak and self-reliant.”–Cheryl HeadJohn Copenhaver: Non-growth-minded individuals in positions of power in publishing houses and other organizations. If you have that power, you also have a responsibility to understand systemic racism, misogyny, homophobia, transphobia, etc. Also, marketing. For instance, it’s terrific that there’s been great energy around reading books by so many incredible Black authors over this past year. The BLM movement has created an occasion to market these writers. Still, you have to ask: Why did it take a social crisis and mass protests for the reading community to realize that there are so many splendid writers of color and that they write books for everyone, not just readers of color. The joy of reading across difference should just be embraced and employed as a marketing strategy. I hope that happens, so this won’t just be a fad, but a lasting trend.

Kristen Lepionka: I think we still have an issue of books with LGBTQIA+ protagonists being specifically labeled as “LGBTQIA+ interest” as if the broader community of crime fiction readers might not be interested—which is nonsense! A good story is a good story. Until publishers put monetary support behind diverse books, readers may not even have the opportunity to discover them, and it becomes a self-perpetuating cycle. Therefore, #ownvoices authors can benefit hugely from the extra exposure that comes with an award like the SinC Pride Award.

CR: What challenges did you face early in your career that you felt were/are specific to LGBTQIA+ authors?

John Copenhaver: When I was shopping Dodging and Burning, I often got rejections that went something like this: “We loved your book, but we don’t know how to market it.” The subtext: We liked your novel, but it’s too gay to convince our editorial board that it would sell broadly. My agent and I kept at it, and we were lucky enough to find an independent publisher (Pegasus) that didn’t see it that way. The big five publishers are changing, but it’s slow. Independent publishers are flexible, creative, and often producing the most exciting work. They’re just more agile.

Kristen Lepionka: I wouldn’t say I experienced any challenges specifically related to LGBTQIA+ authors, other than the occasional reader comment like “I liked this book but I thought it was unnecessary that the main character had to be queer?” Like…whatever.

I will also point out that, in the Before Times when we had things like big conferences (those were the days!), there is a trend of putting all of the queer writers on a few discussion panels that are specifically about queer books. While of course there is value in these conversations, it’s also a missed opportunity to include authors of LGBTQIA+ books in panels that are about other things—trust me, we have opinions about everything.

Cheryl Head: I write a mystery/crime series with a black, queer, female protagonist. That gets my books lumped into a lot of categories, but rarely just mystery. At its heart the Charlie Mack Motown Mysteries are crime novels written with my eye and voice fixed firmly on noir, but with a world view that expands the notions of law and order, justice and problem solving. Charlie Mack is a complex, smart, quirky P.I. who happens to be queer. But in the bookstores, my books might be in the LGBTQ section or the African American fiction section, not mystery. I need that to change.

CR: How has the publishing landscape changed since your debut?

Cheryl Head: There’s much more focus on diversity and inclusion in publishing now because there are so many fine books coming from writers of color. Amazing, rules-busting, genre-bending reads. But, the industry trusts what it trusts. Shawn (S. A )Cosby recently said in a conversation about black crime writing today that the industry has to let writers of color try things and fail. I agree. White mystery writers get that chance all the time. They may have one book that hits; another that misses. If writers of color or LGBTQ writers have a book that fizzles, it’s hard to get back in the batting roster. I made a baseball analogy there. LOL.

CR: Were there missteps you made early in your career that could have been avoided if you’d had access to resources such as Sisters in Crime community resources and/or the Sisters in Crime Pride Award?

Cheryl Head: I’m an introvert. I mean one of the textbook ones. When someone says the word ‘Conference’ I’m like, do you mean I have to talk to some people? As I’ve gotten older my Meyers Briggs status is more in the middle of the introvert-extrovert spectrum. However, if I’d known of the Sisters in Crime community earlier, I’d have been part of a network of writers who understand some people build community differently. The organization has so many resources to help you along your way in your career. They should be applauded for that.

CR: Why are grants and mentorship so important to getting an author’s career started? Who is someone that you’d like to thank for giving you a leg up in your own career?

Cheryl Head: I came to this vocation late in life after a full career in broadcast news and program production. But all along the way I was writing fiction. One of my media bosses, Peggy O’Brien, drove to my house and put Stephen King’s On Writing book in my mailbox. That’s when I knew someone else believed in me as a fiction writer. More recently, I want to thank author Kellye Garrett for plucking me from the hallways at Malice Domestic to introduce me to the Crime Writers of Color community.

John Copenhaver: Lambda Literary as an organization supported me as I figured out what it meant to a gay writer writing about gay life. In 2011, I went to my first Writers Retreat. It was life-changing. I’m always directing young LGBTQ+ writers to Lambda. They’re a great resource and community.

Kristen Lepionka: There are so many folks that have helped in one way or another, but I’d especially like to shout out former SinC President Lori Rader-Day, who I got to know in the Midwest crime writing community, and Kellye Garrett, who was my mentor in 2015 during the Pitch Wars program. If not for Kellye’s support and belief in my work, I’m not sure that I ever would have been published in the first place. Kellye is an incredible champion for #ownvoices authors and just one of the most awesome people I’ve ever had the pleasure to know.

CR: Are there early LGBTQIA+ authors in the annals of crime fiction that you find particularly inspiring for writers getting started now?

Cheryl Head: Nikki Baker, Penny Mickelbury, Joseph Hansen. I’ve noticed more queer stories appearing in gothic fiction and thrillers lately—it’s great to see suspense veer away from straight couples and to see gothic novels leaning into the implications of characters’ mutual obsessions.

John Copenhaver: Joseph Hansen, Katherine V. Forrest, and Michael Nava come immediately to mind. They’re all crime writers writing universally about queer lives. Also, I deeply admire Val McDermid and Sarah Waters.

Kristen Lepionka: I love the Dave Brandstetter series by Joseph Hansen as an early example from the genre. I also have to mention a book that I always talk about when asked this question, but I so far have yet to encounter anyone who’s read it, and that’s really a shame: Dry Fire by Catherine Lewis. It’s a mid-90s novel about a lesbian rookie cop through her days in the academy and as she is starting out on patrol. One of my all time faves.

CR: What do you see as, well, the most LGBTQIA+-friendly subgenres?

Cheryl Head: Speculative fiction, and there’s some great long-form poetry being written by LGBTQ writers. There’s a lot of blending of genre. I’m seeing horror/mystery and a lot of fantasy/mystery.

Kristen Lepionka: The YA category, across all genres, is absolutely awesome for this. And that’s so exciting, because young adult readers are going to turn into adult readers who expect to see diversity in everything they read (yay!) But in terms of right now, I think fantasy is a great place to find LGBTQIA+ stories (Sarah Gailey’s Magic for Liars is an incredible fantasy-mystery hybrid).

John Copenhaver: Crime fiction is a great place to explore and comment on social injustices. Any of the subgenres can do this. I’m particularly interested in noir, because traditionally it’s been a misogynistic and homophobic subgenre—which means that it’s a great place to address those issues and turn them on their heads.

CR: What kinds of queer stories are still underrepresented in the genre?

Kristen Lepionka: I would like to see way more trans stories.

Cheryl Head: Stories of older gay men and lesbians; queer people who aren’t in their twenties and fab forties.

I’d also like to see more stories of intergenerational queer relationships. There are a lot of them, in my experience. There are very few stories with bisexual characters. I write one, and so does Kristen Lepionka. Some of the writing that focuses on minorities in the LGBTQ community can get very political, but I’d love to see more fiction about those tensions.

John Copenhaver: Trans stories. Trans people of color. Queer people of color. There are so many necessary and compelling stories to be told. We need them, but the genre doesn’t have nearly enough. And in some cases—particularly trans people of color—none at all.

CR: Crime fiction is becoming a better space for queer writers and stories, but still has nothing on, say, YA fiction. What changes are you still hoping to see?

Kristen Lepionka: Yes, YA is where it’s at! For adult crime fiction right now, I want to see more Big 5 publishers putting out crime fiction with queer protagonists. And I also want to see books by cishet authors not perpetuating stereotypes. This has obviously come a very long way already, but there is still a ways to go. Well-written queer supporting characters are important to be able to write realistically about the world we live in, even in books that do not center their stories.

Cheryl Head: I’m hoping to see our readers and publishers become just as curious about queer life as the readers and publishers of YA are. Publishers are pivotal in inviting these readers to be excited about these themes and these books. Not only YA, but TV and film producers are way ahead in understanding that a couple of generations of new readers and consumers of other media don’t see queer characters and life as anomalies. Because, to borrow a slogan from the gay rights movement of old: we’re queer, and we’re here!

CR: Can you recommend an #OwnVoices book by an LGBTQIA+ writer out this year?

John Copenhaver: Every month I review a writer in Lambda’s Literary Review. Check it out! This month I featured Edwin Hill. His Hester Thursby series is superb!

Cheryl Head: I have to name two. Both from Lambda Literary Award winners:

Lies With Man by Michael Nava

Murder and Gold by Ann Aptaker

Kristen Lepionka: I’m really looking forward to the release of By Way of Sorrow by Robin Gigl.

-

It may be two months past the winter solstice, but show’s still falling in NYC and there’s plenty of winter weather left to motivate us to stay in and read. These new-in-paperback titles are some of the most exciting mysteries and crime novels around—plus, they won’t break the bank!

Kate Elizabeth Russell, My Dark Vanessa (William Morrow) (2/2)

“[An] exceedingly complex, inventive, resourceful examination of harm and power.” –The New York Times Book Review, Editors’ Choice

Kathy Reichs, A Conspiracy of Bones (Scribner) (2/2)

“Reichs roars back with a Temperance Brennan mystery unlike any that have come before it…” –Booklist

Michael Connelly, Fair Warning (Grand Central Publishing) (2/2)

“Connelly is in terrific form here, applying genre conventions to the real-life dangers inherent in the commercial marketing of genetics research.”—Marilyn Stasio, New York Times Book Review

Silvia Moreno-Garcia, Untamed Shore (Agora, 2/2)

“This thriller sets a quiet tone before building slowly and evenly, showing how a meek teenager trapped by circumstance grows into a strong woman who takes control of her future, though in the end it might change who she is. For fans of Celeste Ng, Alafair Burke, and Kent Anderson.” –Library Journal (Starred Review)

Christina Schwarz, Bonnie (Washington Square Press, 2/9)

Absorbing…poignant, often heartbreaking…Schwarz is a vivid storyteller.” -The New York Times Book Review

John Sandford, Masked Prey (Putnam) (2/9)

“Addictive…Sandford always delivers rousing action scenes, but this time he’s especially good on character, too.”–Marilyn Stasio, The New York Times Book Review

Heather Chavez, No Bad Deed (William Morrow) (2/16)

“Her scrappy female heroine and the breakneck speed in which Chavez unfolds her story make No Bad Deed an exceptional read.” –Shelf Awareness

Daniel Silva, The Order (Harper Paperbacks) (2/16)

“A refreshingly hopeful thriller for troubled times… Silva’s latest broad-canvas thriller starring the much-loved Gabriel Allon will quickly take its reserved seat atop most best-seller lists.” –Booklist, starred review

Alma Katsu, The Deep (Putnam) (2/23)

“Clever and haunting…Katsu is a wordsmith using vivid imagery and beautiful wording to create a story that will leave you wishing there was more.” –Suspense Magazine

Guillermo del Toro and Chuck Hogan, The Hollow Ones (Grand Central) (2/23)

Like a Jack Reacher crime thriller… with a Van Helsing-style demon hunter –The Guardian

-

Humankind is predisposed to the hyperbolic. It was a true in the Titanic’s day as it is today. We love anything that smells of success. We want it huge, we crave it grand: the biggest, the fastest, the most opulent, the richest. We are drawn to such claims like moths to flame.

As much as we love hyperbole, however, it invariably leads to disappointment. This world is not meant for absolutes. Every title has an asterisk or footnote, explaining why any claims must be qualified. The problem is that we love our absolutes and have no patience for the fine print.

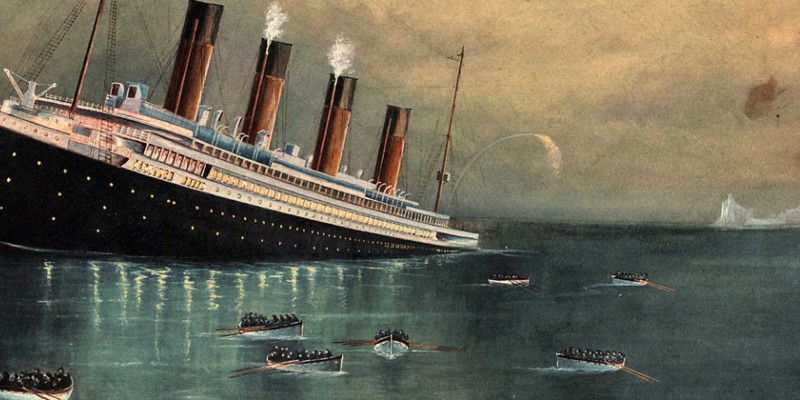

It is no mystery why we’re drawn to the Titanic. In writing my novel The Deep, a reimagining of the sinking of RMS Titanic and its sister ship, HMHS Britannic, I studied the events surrounding two ships in painstaking detail. While these events provide a wealth of things to capture the imagination—the glamorous passengers, the political and social moment in time—it was the parallel between those events and the current day that I found most striking. As The Deep explores, it was an age in which women faced considerable oppression and little legal recourse to improve their situation. It was also a time of great economic disparity: the rich were getting obscenely richer thanks to improvements in manufacturing and trade, while the lower classes sank further into poverty. Colossal tragedy was right around the corner: the Spanish Flu epidemic was a few years off, as was the Great War. There was a sense of giddy optimism but, at the same time, a creeping realization that maybe we were only pretending that things were great.

RMS Titanic captured the popular imagination when it was launched in late March 1912. It was born into grandeur, the largest passenger ship of its day (though, given the arms race among the world’s shipbuilders, it would be eclipsed by the SS Imperator less than a year later). A key selling point was safety. Passengers were right to worry: sinkings were more common than airplane crashes are today. A White Star vice-president went so far as to claim the ship was unsinkable. As boasts go, it was clever: every day the ship doesn’t sink, you look like a genius. Too bad for White Star Lines, the ship sank on the fourth day of the voyage.

This ridiculous boast made the Titanic forever synonymous with hubris. The ship’s funnel tops sank under the waves in three hours once it struck the iceberg. Common sense would tell you that no ship is unsinkable, and certainly not one weighing over 50,000 tons. Imagine if modern airplane manufacturers promised that a particular model of aircraft would never fall out of the sky. Yet much of the public chose to embrace this threadbare claim.

Did White Star Lines suffer any consequences for its bald-faced lying? J. Bruce Ismay, CEO of White Star Lines, was a passenger aboard the Titanic for its maiden voyage. Ismay managed to escape on one of the lifeboats, though he was widely criticized for his cowardice. Still, he managed to live with this shame to a ripe old age, something you can’t say about John Jacob Astor, the richest man in America, or the other 1,500 people who drowned in the freezing cold Atlantic waters.

As the Titanic goes to show, it is easy for humans to cling to denial when faced with existential threats like spiraling poverty and consolidation of power by elites. How does one prepare for doomsday? Is it so unexpected that many would prefer to believe the lies and would refuse to see the iceberg until chunks of it came crashing onto the deck?

In real life, Titanic’s sinking provided a wake-up call. A review of the incident informed industry-wide improvements in both design and safety procedures. The launch of Britannic, the last ship in the line, was delayed so that improvements could be made to the hull design, changes that probably accounted for the far lower loss of life when the Britannic, now a hospital ship, struck a sea mine and sank on November 21, 1916 (approximately 1500 people were killed when the Titanic sank, only 30 on the Britannic).

What lessons can we take away from the sinking of the Titanic? It reminds us that massive self-deception can’t be sustained, that after every disaster there’s going to be a reckoning, an attempt to set things right. I think that’s one reason so many people remain fascinated with the Titanic: because even though we know its sad ending, we know that come the dawn, there’s going to be a rescue ship on the horizon.

*

-

He walked, feeling his body fill with blessed tiredness. Vyrin knew every root, every hole on this path, and he looked forward to seeing the pasture on the left, fenced by rowan trees—the berries would be ripe in color by now—and then he would encounter the sweet, gentle chimney smoke from the farm. The walk both tired and invigorated him; his recent fears seemed silly. I guess I really am old, he thought. I’ve become neurotically fearful.

He could see the cathedral from the last turn. It stood on a stone outcropping that divided the top of the valley. The yellow façade, framed by two bell towers, continued upward from the vertical plane of the cliff. This church was much larger than the cathedral in town. It had been built here, in the mountains, by the pass, on an ancient pilgrimage path, its majestic vaults signifying the depth and significance of someone’s epiphany, an acquisition of faith that took place in the silent solitude of the outcropping.

Beyond the cathedral’s back wall, in the shade of chestnut trees, lay a small outdoor restaurant with good food. The regular waiters recognized him—or pretended to. They did not try to chat but smiled respectfully. Here he fully felt he was Mr. Mihalski; he took that pleasant and exciting sense of connection, the merging of true and invented identities, as a special gift which he brought back home in the trolley that traveled along the bottom of the valley.

Today the courtyard was full: a summer weekend. There was only one free table, at the edge behind a wide-branching tree. Next to the sandbox and swings. That meant frenzied children would run around, making noise. Vyrin preferred sitting among people dining sedately, behind strangers, in the buzz of calm conversation, the clinking of knives and forks, where it is hard to eavesdrop, photograph, or take aim.

Vyrin looked at the diners: Was anyone about to leave? No, they were all relaxed, in a merry lazy mood. The brunette at the nearby table had a provocative drop of crème brûlée on her upper lip. She didn’t wipe it away or lick it off, knowing how seductive and sexy it looked. She wore a dark metal necklace resembling a dog collar—a sign of exotic passions, kinky torment insolently displayed in a restaurant by a church.

The brunette’s sister, in her eighth month at least—her swollen belly had pulled her dress up to reveal strong, plump legs— was eating chocolate cake and schnitzel simultaneously with great appetite, as if the infant were overripe, born but remaining in the womb, and demanding his share of the feast.

Vyrin wanted to leave. He was dizzy with fatigue, the heavy scents, the density of human voices—the village was small, every- one was related in some cousinhood, redolent of fetid incest that repulses outsiders like salty seawater.

But he felt the charm of the play of light in the chestnut leaves, the clay-blue tablecloths pressed so that there wasn’t a single wrinkle, the high-necked bottles of ice water, the harmless murmur of neighbors, the balletic moves of waiters balancing enormous trays of six to eight plates on their shoulders, where atop the delicately tossed salad looking as if arranged by a coiffeur, the leaves green with reddish veins, floated golden-breaded schnitzels, resembling torn blobs of copper blasted from a smelting furnace.

Yum, yum, yum the pregnant woman crooned to her unborn infant. The limestone angel with a blurred face blew silently into a golden trumpet over the back entrance to the church. He felt himself basking in the insouciant summer that enveloped the entire world.

Vyrin ordered beer and a steak. Wasps flew toward the fra- grant hops. They were not attracted by the remains of dessert on nearby plates, rivulets of honey and chocolate—only by hops. They crawled around the rim of the mug and tried to land on his shoulder, his hand, circling persistently and stubbornly. He waved them away, almost spilling his beer. He had a bad allergy to insect bites. Back when he was in the service, the doctors said it would get worse over the years and offered to give him a medical discharge. Wasps, wasps, wasps—he moved the mug away, flicked a wasp, and then another, from the table, regretting he had not brought a jacket.

A sting. On the nape of his bare neck. Sudden. As painful as an injection administered by an inexperienced nurse.

He slapped the bite, but the wasp was gone. He turned, intent on the pain, and noticed a man walking away and getting into a car. The license plates were not local.

His neck ached. The pain spread up and down, to his shoulder, cheek, temple. He felt something microscopic in the wound—probably the stinger.

His vision clouded. His breathing became shallow. His body was engulfed by dry heat. He got up with difficulty and headed for the toilet.

Rinse. He needed to rinse with cold water. Take a pill. But wash first. Such pressure in his throat! He might not be able to swallow the pill. His skin was burning.

He could barely stand. He leaned against the sink, clumsily splashed water on his face. The wasp sting was on the right side of his neck, and his right arm was stiff. He shoved the tablet into his throat. The mirror showed a gray, bloodless, but swollen face, as if something was trying to undo the plastic surgery and force his old look back on him.

The tablet should have worked by now. It was the latest medicine.

But it wasn’t working.

A rash broke out on the gray skin. His stomach cramped. He sank to the floor, staring at the tiles—and understood. That man had not been a customer at the restaurant. Locals didn’t park where he had stopped the car.

With a final effort, he rose and holding on to the walls made his way into the corridor. His constricted throat kept him from screaming, calling for help. On the porch, he bumped into a waiter carrying a tray of bottles and wineglasses. The waiter assumed he was dead drunk and moved aside. He fell from the porch, taking the waiter with him, hearing the crashing glass and hoping that everyone noticed and was looking. He hissed and gurgled into someone’s ear:

“Ambulance . . . police . . . murder . . . not drunk . . . poison . . . I was poisoned.”

And he collapsed, still hearing the sounds of the world but no longer understanding what they meant.

The two generals had known each other a long time. They had served together under the red flag with hammer and sickle.

The lieutenant general had been chairman of the Party Committee then. And secretly, he was head of the numbered department, which was not indicated even in the top-secret staff register. The major general had been his deputy, successor, rival. The Party Committee was long since disbanded. But the department remained. It survived all the reforms of their agency, all the changes in names and leaders, divisions and mergers. As ever, it had only a number and was not included on the organizational chart.

They were in the surveillance-free room and could talk without worry of being overheard. However, their language, laden with professional euphemisms, deceitful by nature, allowed the men to formulate sentences so that they could be interpreted as expressing either conviction or doubt.

They both knew that their conversation would most likely result in the execution of an order, unspoken, not registered in the system of secret case files, but which would still require sanction at the very top. Both generals wanted to avoid responsibility for a possible failure but to claim his share of benefits in case of success. Each knew what the other was thinking.

“According to the information of our neighbors, he died after four days in an induced coma. The organism almost coped with it, you might say. We can’t rule out that the dose was insufficient. Or its method of introduction was wrong. Perhaps he had time to take antidote pills. Or some other outside substance lowered the effectiveness of the preparation. Weather could have been a factor. Air pressure. It was in the mountains, high altitude. Before passing out, he had time to say he had been attacked. The waiter was a former policeman. Someone else might not have paid attention, thought it was just a drunken fantasy.”

“So did the neighbors want the incident to attract attention or not?”

“Naturally, they don’t give us details. They may want to put a good face on a bad game: that they had anticipated this becoming public from the start.”

“Well then . . . Let’s move on to our information.”

“An interagency investigation team has been set up. International protocols have been put into action. They’re bringing in foreign chemistry experts. There are very few specialists of that quality. They called in four people. Three are known to us, they are on file. They are people with big names. But the fourth one does not appear in the files. There is no open information about him. At our request, competent agents have been questioned. No one has heard of such a scientist. We are continuing the search; we’ve put the overseas stations on it.”

“Looks as if he’s a know-nothing, unknown professor.” Both gave a restrained chuckle.

“The source says that this professor was not involved in police cases before. He might have been used by the military, but the source does not know about that. The source is not directly involved in the investigation. His future abilities are limited. He is only coordinating the cooperation of his country’s police.”

The generals fell silent. They could picture the bureaucratic strategy in an extreme event: controlled chaos, mountains of paperwork, coordination, documents that have to be shared with other agencies. Forced repeal of secrecy regulations. Temporary commissions. Outside specialists who would otherwise never be allowed through the door. Whether the neighbors’ action had gone according to plan or not, it gave them a wonderful opportunity, which the neighbors did not recognize.

“There is a high likelihood that this professor is Kalitin,” the deputy said at last.

“Yes, that probability exists. It fits his scientific profile. Exactly. And since suspicion naturally falls on our country, it’s very reasonable to bring him in. If, of course, he is still alive. And of sound mind.”

“He’s only seventy. I assume he takes good care of his health.

Physical and mental.”

“We have an address?”

“The source reported it.”

“Will that compromise the source?”

“Can’t say with certainty.”

“Is he valuable?”

“Moderately. Because of his past in the GDR he has not been promoted readily. And he’ll be retiring soon.”

“Understood. An order must be given to the station. Let them check it out. Send the very best.”

“If they determine it’s him, we can prepare the event. And start the coordination.”

“Interesting. If it’s Kalitin, then it’s very interesting.”

“Neophyte.”

“Yes. Neophyte. His favorite.”

“None of our operatives today have worked with Neophyte.” “I am aware of that.”

“But there is one candidate—Shershnev. He did an operation with one of Kalitin’s early versions. He doesn’t have any experience abroad, however. But he was born and grew up there. His father was in our army. He knows the language well. Here’s his file.”

“I’ll take a look. Send all the necessary orders immediately.”

“Yes, sir.”

The deputy left the room. The general opened the file.

__________________________________

-

The Baker Street Irregulars, Sherlock Holmes’s organization of motley street urchins, are going to get their own Netflix series. It’s a dark show, full of supernatural mysteries, but the paranormal activity is not the only modification to the Sherlockian world you know and love. The program, titled The Irregulars, posits that the group is manipulated into solving dangerous supernatural crimes by Dr. Watson (who is evil)—feats for which his sketchy business partner Sherlock Holmes gets all the renown. The series, which consists of eight episodes, is due to make its streaming debut on March 26th.

In an interview with the BBC, writer Tom Bidwell sums up the series as a new interrogation of Holmes’s legacy, concentrating on the construction of his mythos: “Sherlock Holmes had a group of street kids he’d use to help him gather clues so our series is what if Sherlock was a drug addict and a delinquent and the kids solve the whole case whilst he takes credit.”

The Baker Street Irregulars, who are for the most part children, made their first appearance in the inaugural Holmes novella A Study in Scarlet. They are led by a boy named Wiggins, and they perform intelligence work around London.

“It’s the Baker Street division of the detective police force,” explains Holmes to a startled Watson, when half a dozen dirty children burst into their apartment one day, in A Study in Scarlet. Holmes elaborates: “There’s more work to be got out of one of those little beggars than out of a dozen of the force. The mere sight of an official-looking person seals men’s lips. These youngsters, however, go everywhere and hear everything. They are as sharp as needles, too; all they want is organisation.” For their work, Holmes pays them each one shilling per day, plus expenses.

Holmes calls them “the Baker Street Irregulars” for the first time in the following novella, The Sign of the Four, which takes place seven years after A Study in Scarlet. The kids (now teenagers) make a few appearances throughout the Holmes stories, and have been featured in several adaptations, most recently as Holmes’s “Homeless Network” in the BBC Sherlock series starring Benedict Cumberbatch.

In the new series, the leader of the Irregulars is not Wiggins, but a preteen girl named Bea (Thaddea Graham), who looks out for her younger sister Jessie (Darci Shaw). They are accompanied by three other children named Billy (Jojo Macari), Spike (McKell David), and Leopold (Harrison Osterfield).

The cast stars Henry Lloyd-Hughes as the shady Holmes, and Royce Pierreson as the “sinister” Dr. Watson.

Take a look at the official teaser here:

-

What is the Purpose of Algonkian?

What is the Purpose of Algonkian?

To give writers in all genres a realistic chance at becoming published commercial or literary authors by providing them with the professional connections, feedback, advanced craft knowledge and savvy they need to succeed in today's extremely competitive market.

What is Your Strategy for Getting Writers Published?

What is Your Strategy for Getting Writers Published?

- A model-and-context pedagogy that utilizes models of craft taken from great fiction authors and playwrights, thereby enabling the writer to pick and choose the most appropriate techniques for utilization in the context of their own work-in-progress.

- Emphasis on providing pragmatic, evidence-based novel writing guidance rather than encouraging multiple "writer group" opinions and myths that might well confuse the aspiring author.

- Our insistence that a writer's particular genre market must first be thoroughly understood and taken into consideration when it comes to the planning of the novel, and on every level from narrative hook to final plot point--thus clearly separating us from the MFA approach found at university programs like Iowa and Stanford.

- Our conviction that you were not born to be a good or great author, but that you stand on the shoulders of great authors gone before. Their technique and craft are there for you to learn, and learn you must as an apprentice to your art. Every success you achieve is based on hard work and evolving your skills and knowledge base.

- Our instructional and workshopping methods, as well as our pre-event novel writing guides and assignments which are the best in the business.

How are Algonkian Events Unlike Many Other Workshops and Conferences?

How are Algonkian Events Unlike Many Other Workshops and Conferences?

- More than sufficient time for productive and personal dialogues with faculty. No "speed" dating-like pitch sessions.

- Critical MS and prose narrative critique provided by faculty only, not attendees (no MFA methodology).

- Comprehensive 86-page novel-and-fiction study guide.

- Extensive pitch prep before events with agents or publishers.

- As noted above, unique and challenging pre-conference assignments that focus on all major novel elements.

- An event focus on market-positioning, high-concept story premise, author platform, and competitive execution.

- Emphasis on pragmatism and truth telling. No false flattering or avoidance of critical advice to spare the writer's feelings. Thin skins need to go somewhere else.

- No tedious lectures, pointless keynotes, or bad advice.

- Faculty chosen for wisdom as well as compassion - no snobs or bad attitudes.

How to Know When My Novel is Ready for a Program or Event?

How to Know When My Novel is Ready for a Program or Event?

When is it not? The novel-in-progress, even if only a concept, is ready to be examined and properly developed no matter the stage because the process always entails approaching story premise and execution in a manner that is productive. In truth, it's a process that should have begun as soon as the work was conceived. Therefore, the stage of the novel or number of years working on it is irrelevant. Any time is a good time to begin doing it correctly.

Do you Have Success Stories?

Do you Have Success Stories?

Comments, Careers, and Contracts

Which Events or Programs to Attend First

Which Events or Programs to Attend First

Novel Writing Program online and/or one of the workshop retreats followed by a New York prep seminar followed by the New York Pitch Conference OR the Novel Editorial Service (MTM) followed by New York prep seminar and New York Pitch, in that order. These are best case scenarios wherein money isn't tight. We will provide an overall discount of 26% on all events in either string if payment is made upfront for the entire grouping. Contact us for more information.

What Genres do You Work With?

What Genres do You Work With?

Upscale and literary, memoir and narrative non-fiction, mystery/thriller and detective/cozy genres, urban fantasy, YA and adult fantasy, middle-grade, historical fiction, general fiction and women's fiction. Our agent and publisher faculty handle all genres.

How Does Algonkian Differ From An MFA Approach?

How Does Algonkian Differ From An MFA Approach?

Algonkian emphasizes writing-to-get-published, creation in the context of heart, wit, and market knowledge. We teach writers to think pragmatically about the development of their ms while retaining their core values for the work. Our motto is "From the Heart, but Smart." College MFA programs do not prep a writer for the cold reality of the current publishing climate. Many of our most grateful writers are graduates of MFA programs.

How do Writers Interact With Agents and Publishers?

How do Writers Interact With Agents and Publishers?

The model for the pitch is a "book jacket" the writer creates with the help of the workshop leader prior to the pitch session. The process is part of a longer evolution the writer begins even before arriving at the conference. Once the pitch is accomplished, the agent interacts with the writer in a Q&A session. The workshop leader then follows up with the writer to create a plan for publication, i.e., a step-by-step post-conference process the writer must undertake in order to stand a realistic chance of having his or her manuscript published.

What is the "Pre-event Work" All About?

What is the "Pre-event Work" All About?

Writers are given several different types of relevant assignments, story and pitch models, as well as a considerable amount of reading on the subject of advanced craft directly applicable to their work-in-progress. The idea is to prep the writer before the event so they can hit the deck running and share with us a common language. As a bonus, the pre-event work saves us from wasting time with extra handouts. Samples of the pre-event work, readings, and guides can be found here. -

Another week, another batch of books for your TBR pile. Happy reading, folks.

*

Russ Thomas, Nighthawking

(Putnam)“Outstanding. . . Thomas adeptly develops his diverse cast, but the novel’s real power lies in its intricate structure—the mystery surrounding the body is impressively deep, the various levels of tension are relentless, and every chapter ends with a narrative punch to the face. This police procedural is virtually unputdownable.”

–Publishers Weekly

Steve Berry, The Kaiser’s Web

(Minotaur)“Berry keeps finding enticing alternate-history mysteries for Malone to solve . . . Keep ‘em coming.”

–Booklist

Joe Ide, Smoke

(Little Brown)“Ide has displayed a rare ability to mix dark comedy and gut-churning drama…mixmaster Ide’s compulsion to blend light and dark (Isaiah’s confrontation with the serial killers, while gruesome, takes the form of “a slapstick movie shot in a burning insane asylum”) affects the two plots in surprising ways, again producing an emotion-rich form of character-driven tragicomedy, but one in which peril forever loiters in the shallows.”

–Booklist

Nalini Singh, Quiet in Her Bones

(Berkley)“Singh sustains tension throughout, delivering a lushly written, multilayered mystery that will keep readers guessing. Susan Isaacs fans, take note.”

–Publishers Weekly

D.W. Buffa, The Privilege

(Polis)“Buffa’s characters are compelling; the dialogue authentic and well crafted. With the current political upheaval, Buffa’s newest novel hits home in more ways than one. The author draws on his own experience as a criminal defense attorney to render realistic courtroom proceedings. Highly recommended for lovers of legal and political thrillers.”

–Library Journal

György Dragomán, The Bone Fire

(HMH) (Trans. Ottilie Mulzet)“A poignant coming-of-age tale set against the backdrop of regime change.”

–Kirkus Reviews

Justin Fenton, We Own This City

(Random House)“Baltimore Sun reporter Fenton, whose coverage of the Baltimore riots that followed the death of Freddie Gray led to a Pulitzer Prize nomination, debuts with a searing look at that city’s recent police corruption scandal. . . . Fenton’s detailed narrative makes the tragic consequences of the [Gun Trace Task Force’s] graft palpable.”

–Publishers Weekly

Tim Brady, Three Ordinary Girls: The Remarkable Story of Three Dutch Teenagers Who Became Spies, Saboteurs, Nazi Assassinsand WWII Heroes

(Citadel)“Historian Brady (Twelve Desperate Miles) delivers a dramatic group portrait of three teenage girls who fought in the Dutch resistance movement during WWII. Brady conveys the inhumanity of the period with precision…. This moving story spotlights the extraordinary heroism of everyday people during the war and the Holocaust.”

–Publishers Weekly

Tori Telfer, Confident Women: Swindlers, Grifters, and Shapeshifters of the Feminine Persuasion

(Harper Perennial)“Whether she’s describing women pretending to be doctors, socialites, or just another nice lady who desperately needed help, Telfer dishes up their scandalous schemes for true-crime fans to relish.”

–Booklist

Nicole LaPorte, Guilty Admissions: The Bribes, Favors, and Phonies behind the College Cheating Scandal

(Twelve Press)“[A] riveting rundown of Operation Varsity Blues…Readers will be captivated by this entertaining look behind the headlines.”

–Publishers Weekly -

I’ve always been impressed with the level to which authors, readers, and editors support each other in the crime fiction community, but the folks at #pitchwars go above and beyond. I interviewed some of the wonderful mentors and mentees of Pitch Wars to find out how their community works to help new authors break into the industry. We talked about gatekeeping, getting started, and how to gracefully take an edit, among other things. Thanks to Kellye Garrett (Hollywood Ending), Layne Fargo (They Never Learn), Mia P. Manansala (Arsenic and Adobo), Mary Keliikoa (Denied), and Dianne Freeman (A Lady’s Guide to Mischief and Murder) for answering all my questions about this fantastic program. Follow #pitchwars on Twitter to keep up with all the news.

__________________________________

To get started, can you give us a brief overview of what Pitch Wars is?

__________________________________

Kellye Garrett: Pitch Wars is a mentoring program where published/agented authors, editors, or industry interns choose one writer each to mentor. Mentors read the entire manuscript and offer suggestions on how to make the manuscript shine for the agent showcase. The mentor also helps edit their mentee’s pitch for the contest and their query letter for submitting to agent.

Since Brenda Drake started Pitch Wars in 2012, we’ve had over 250 success stories of mentees getting agents and/or publishing deals. Some notable alums include Tomi Adeyemi, Helen Hoang, Zoje Stage and others.

__________________________________

How can people get involved in Pitch Wars?

__________________________________

Kellye Garrett: They can visit the Start Here page on our website: http://pitchwars.org/new-start-here/. They can also just hang out on the #pitchwars hashtag on Twitter. Thousands of people use it and have found friends, critique partners and just an amazing community.

__________________________________

What is the best way to support the work that Pitch Wars is doing?

__________________________________

Kellye Garrett: The best way would be to share info on Pitch Wars with any emerging writers you know. For example, I found out about Pitch Wars on the Sisters in Crime Guppies board and in turn, I have shared info about it with anyone who will listen. I know at least two mentees who learned about it through me just talking it up and decided to apply.

__________________________________

How has mentorship helped you in your writing career?

__________________________________

Mia P. Manansala: I’m very lucky that my mentor, Kellye Garrett, has not only become my co-mentor, but a good friend. She is a constant cheerleader, sounding board, and go-to for questions about the publishing industry. I don’t know how I would’ve survived having to return to the query trenches and being on sub with a new agent and new novel without her. Plus I still use all the tools and techniques I learned as a mentee in my writing routine.

Layne Fargo: When Nina Laurin picked me as her Pitch Wars mentee back in 2017, I had no idea how to take my raw, messy manuscript and turn it into the polished, compelling story I saw in my head. She helped me close that gap and take my work to the next level. I truly have no idea where I’d be now without her guidance.

Kellye Garrett: My debut novel, Hollywood Homicide, was a Pitch Wars novel in 2014! You can read my pitch here: http://pitchwars.org/71-iou-adult-mystery/. My life changed when Sarah Henning selected me and my book to mentor. I met my amazing agent, Michelle Richter, through the program. I sold my Pitch Wars novel to Midnight Ink. It went on to be the most decorated debut mystery of the year when it was awarded the Anthony, Agatha, Lefty and IPPY awards for best first novel. And most important, it created a sense of community that I still depend on to this day.

Dianne Freeman: Working with my mentor, E.B. Wheeler was the first time my writing had ever been edited. I didn’t have a critique group or even a critique partner. I was just floundering on my own. Through PitchWars I gained an understanding of what it was like to work with an editor and produce results within a stated deadline. And if those results weren’t quite hitting the mark, to do it again. And again. Through this process I became a better writer and a better editor.

Mary Keliikoa: Being mentored has meant everything. When I came back from a long writing hiatus (15 years to be exact), I didn’t know anyone who was writing and I felt a bit on an island. Being mentored meant that I had an experienced voice who could help me navigate the new landscape of writing—not only what was happening in publishing, but what was happening in the mystery genre itself. Of course the feedback I received on my book helped me move in the direction of being published, but having that someone who believed in my work was equally as important to keeping me motivated.

__________________________________

What makes for a great pitch?

__________________________________

Dianne Freeman: Character, conflict, and stakes—and nothing else. I pitch a story to myself before I ever write it. If it has those three elements, I know I can write the story. Then I memorize it. I’m under contract, so I don’t have to pitch to an agent or editor, but I do speak to readers and booksellers. When they ask what I’m working on, I don’t want to go into a rambling description that keeps veering from the point—which is exactly how I talk—so I give them my pitch. Distilled to those three elements, the pitch should elicit the same reaction you want from readers when they read the book—excitement, interest, a shiver, or maybe a laugh.

Mary Keliikoa: The basics of the pitch are knowing who the main character is, what the goal is they’re striving for, and what’s at stake if that goal is not met. When you can add a layer of voice to that pitch, it turns into great.

Mia P. Manansala: Intriguing comps and specificity. Know exactly what your book’s about and who you’re trying to sell it to.

__________________________________

What has your experience been like with the publishing industry? Have gatekeepers helped or hindered your career?

__________________________________

Kellye Garrett: As a black woman, this is such a tricky question. I think most people will agree that I’m one of the most outspoken people in crime fiction when it comes to diversity. It’s so amazing to see editors and agents seeking out crime fiction by writers of color now because it was not like that five years ago when I was looking for an agent and later was on sub. It’s so hard because as a POC, you never know why someone is rejecting you. Is it because they didn’t connect with the book or was it because they don’t think that a book where the black woman actually solves the crime will sell well? Hollywood Homicide was on submission for over a year before Terri Bischoff at Midnight Ink took a chance on it. And I will say this. I had minimal edits on my debut. So the book that won all those awards and got two starred reviews is the same book that Michelle and I were trying to sell five years ago and was getting rejected left and right.

Layne Fargo: Gatekeepers kept me out of the industry when I was querying my first manuscript—and they were right to! That book wasn’t ready, and neither was I. Since signing with my agent Sharon Pelletier post-Pitch Wars, I’ve had a wonderful experience. She’s a relentless advocate for me and my work, and I trust her judgment completely (especially since she was wise enough to form-reject that first book).

Mia P. Manansala: With my Pitch Wars novel, I received lots of positive feedback from agents and editors (including several offers) but it never went anywhere because acquisitions teams didn’t find it “marketable.” According to them, traditional mystery (my genre) skews older and white, and my queer, Filipinx millennial solving a murder at a comic book convention didn’t have an audience. I obviously disagree, but it’ll be some time before those with power in the publishing industry reflect the demographics of the world around them.

Dianne Freeman: Gatekeepers haven’t really played a part in my publishing experience. At least part of the reason for that is PitchWars, where I connected with my agent. If not for PitchWars, I wouldn’t have subbed to her since her bio stated she probably wasn’t the best match for historical fiction. Due to the nature of the Agent Showcase, she picked me, rather than the other way around. In this way, PitchWars allows a writer to bypass a few of the gatekeepers, including the one in our own brains. As it turned out, we’re a wonderful match.

Mary Keliikoa: It’s been educational for sure. I have enjoyed seeing the different stages required to bring a book together, but my experience is it moves very slow. I’ve had to develop the skill of patience, which I didn’t possess much of prior!

__________________________________

What are some pointers you can give for those who are interested in mentoring up-and-coming authors?

__________________________________

Kellye Garrett: The biggest thing is recognizing the power dynamic. Even though mentoring is really just someone a bit farther in their career giving notes and advice to someone else, it doesn’t always feel like that to the mentee. What you as the mentor says is bond. A lot of emerging writers have never had a hard critique before as well. It’s like their parents or significant other being like, “This is great.” So it’s hard to get that first real set of notes. It’s not uncommon for someone to get feedback and want to give up writing. So just be mindful of how you interact and say things, especially when giving feedback. Also, just remember this is their book and their voice. It’s not yours. So please don’t try to make them mini-mes.

Layne Fargo: Remember that you’re there to help your mentee achieve their vision for their book—not your own vision. You can give advice and suggest changes, but final decisions should always be up to the author themselves.

Mia P. Manansala: Check your ego at the door. You do not have all the answers and you are not there to stake your claim on their story. Ask questions. Guide them. Help them tell THEIR story the best way they know how. Finally, empathy and kindness go a long way. Writing is a tough gig no matter where you are in your journey, and the perceived power imbalance between mentor and mentee can make it tough for your mentee to speak up when they disagree with you. Make sure your relationship is a safe space, but also keep your boundaries very clear.

__________________________________

Pitch Wars provides not only mentorship, but a sense of community. How has the community of Pitch Wars made an impact on your life?

__________________________________

Layne Fargo: Almost all of my close friends and creative collaborators in the publishing world are people I met through Pitch Wars. As an extreme introvert, Pitch Wars was the perfect way to meet lots of people from the safety of my browser screen.

Mia P. Manansala: The community is absolutely the best part! I was part of the 2017 class and our group is still very active–cheering each other on, helping with beta readers and critique partners, giving book/media recommendations, and just providing a safe place to discuss the difficulties of publishing.

Dianne Freeman: It’s such a thrill when you find someone who gets you. When you find over 100 people who get you, it’s a community and there’s no feeling quite like that. We’re all striving for the same goal and sharing the same experience. We commiserate with each other and cheer each other on.

Mary Keliikoa: Having kindred spirits has been very impactful. We all understand the angst of editing and waiting and wondering. Having a place to land with people who do get you on that level, is incredible. And I think long lasting friendships come out of that as well. One of my best friends that I correspond almost daily with was a mentee the same year as I was, and another one of my close friends was an applicant. And if I’m ever wanting a sprint partner, or just to lament, I just hop over to my 2016 Pitchwars community and there is always someone there to sprint with or talk me down. There is a glue to the community that continues no matter where our paths have led us.

__________________________________

Pitch Wars is one of many organizations advocating for more diversity in publishing. What changes would you like to see in the industry?

__________________________________

Kellye Garrett: Diversity is trendy right now but trendy implies it’ll go away. I want diversity to be status quo, where it’s no longer a big deal to see a cozy written by a black writer or a domestic suspense written by someone who is Latinx. After the huge success of Walter Mosley and Terry McMillan in the 90s, black mystery novels were hot! But with some exceptions, most of those amazingly talented writers publishing mysteries in the 90s aren’t still writing those series today. We need to not just publish marginalized writers, we need to keep publishing them.

Layne Fargo: Publishing obviously needs more diverse contributors at all levels. One of the most impactful, immediate changes publishers and agencies could make would be offering more remote work opportunities, so people don’t have to scrape by for years in an expensive city like New York just to break into the industry. Everything about Pitch Wars has been remote since the beginning, and it’s working just fine!

Mia P. Manansala: Widespread representation across all aspects of publishing: agents, editors, acquisitions/marketing/publicity teams, etc.

What books get represented/acquired, the advances they receive, how they’re marketed (or even which books get a marketing push and which are left to struggle on their own) are so often reliant on the white, cishet experience, which leads to a huge imbalance and lack of nuance in representation.

Mary Keliikoa: Representation just needs to continue to happen on every level from the top down. That’s the only way there will be lasting change. Open hearts, open minds, and the willingness to know each other and have compassion for each of our journeys. I have hope that we will just continue to work down the path together and keep opening it up. There’s no other option. It has too happen and I’m encouraged by the outpouring that it will.

__________________________________

What’s your advice for young writers and those new to writing crime fiction?

__________________________________

Layne Fargo: Read a lot (not just crime fiction: every kind of fiction) and get over your perfectionism. You have to write the awful version of the book before you can even begin to figure out what the good version looks like.

Dianne Freeman: You really need to love doing this. If you don’t you should choose another career. Writing a book takes a long time and a lot of hard work (usually before and after your paying job). And there are so many ways it can break your heart. Maybe it will be after your umpteenth rejection, or maybe a one-star review, or when your editor tells you that you have to cut 100 pages from your manuscript that just isn’t working. If you write for yourself—for the joy of it, none of that will matter. You get to do what you love!

Mary Keliikoa: Join groups that are crime leaning. Sisters in Crime is great and their Guppies group focuses on the unpublished writer who wants to continue to network and build their skills. Mystery Writers of America is another great organization. In addition, just keep creating a network of people in the industry and experts outside the industry so you have a group to call upon as you write your crime novels.

__________________________________

What are some recent or upcoming books you’d like to recommend, either from the Pitch Wars community or the genre as a whole?

__________________________________

Kellye Garrett: I’m super super super excited for Mia’s book, Arsenic and Adobo, and not just because she’s one of my best friends. She has an amazing writing style and is a much needed voice in crime fiction. Her books feel like true millennials, which is rare in cozies.

I begged Halley for an early copy of The Lady Upstairs, and it was worth every annoying message I sent because the book is amazing. Halley has the type of voice that makes you never want to write again because you won’t be able to match it.

Non Pitch Wars, I loved Alyssa Cole’s debut thriller, When No One is Watching. (I also begged Alyssa for an early copy of that), S.A. Cosby’s Blacktop Wasteland (begged for an early copy of this as well) and David David Heska Wanbli Weiden’s Winter Counts (would have begged for this one but they accepted me on Netgalley so I didn’t have to. Yay!) These are all #ownvoices thrillers that weave cultural elements/issues with an amazing story.

Layne Fargo: Well, of course I have to recommend my mentee turned co-mentor Halley Sutton’s debut novel The Lady Upstairs, out this November from Putnam. Halley’s book is a scorching, gorgeously-written feminist noir that I haven’t been able to get out of my head since the moment it appeared in my Pitch Wars inbox.

Dianne Freeman: If you enjoy historical fiction, my mentor E.B. Wheeler released Wishwood in January, and The Royalist’s Daughter in March.

PitchWars alum, Julie Clark’s thriller, Last Flight is on my TBR. I’m a big fan of Kristen Lepionka’s Roxane Weary. Once You Go This Far, book 4 in the series, released in July.

Outside of the Pitchwars community I have two historical mysteries on my radar: M.L. Huie’s Nightshade and S.M. Goodwin’s debut mystery Absence of Mercy came out last fall.

Mary Keliikoa: Anything from Kellye Garrett, Dianne Freeman, Kristen Lepionka and the others on this fine Roundtable that I’m proud to be part of! I also really enjoyed Pitch Wars alum’s Meghan Scott Molin’s book The Frame Up. And as a PI fan, I have to add Tracy Clark’s recently released What You Don’t See. It is excellent.

Mia P. Manansala: My Pitch Wars class has been KILLING it lately. YA mystery is a hugely slept-on category in the mystery community and that’s our loss since kid lit is where some of the most interesting and fresh takes are happening. Two queer YA mystery novels out last year from my class are Throwaway Girls by Andrea Contos and You’re Next by Kylie Schachte. I’ve been wanting to read these books since I first saw their pitches back in 2017 and I’m so excited they’re here.

On the Adult side of crime fic, They Never Learn is Layne Fargo’s sophomore novel (her PW novel Temper came out last year and is a fast, sexy ride), which came out last fall.

As for non-crime fic recs from my class, definitely check out Rena Barron and Roseanne A. Brown for diverse YA fantasy.

__________________________________

What are some challenges you’ve faced in the quest for publication?

__________________________________

Layne Fargo: Like most writers, I have several books in the drawer. My first manuscript racked up over 100 rejections— including two consecutive failed attempts to get into Pitch Wars!

Mary Keliikoa: I think probably the hardest challenge was during the querying stages and when the rejections rolled in, trying to understand what the agent had wanted so that I could make my manuscript better. Often, and understandably so, they weren’t very specific which meant I spent a lot of time trying to decipher what different rejection wording actually meant.

-

The CrimeReads editors recommend the month’s best new crime nonfiction.

*

Ellen McGarrahan, Two Truths and a Lie

(Random House)In 1990, Ellen McGarrahan, then a reporter working for the Miami Herald, attended the execution of Jesse Tafero. The bungled execution stayed with her for a long time after, and the haunting only grew worse when she learned, years later, that there was serious doubt as Tafero’s conviction. McGarrahan eventually left behind life as a reporter and turned private investigator. From her new perspective, she decided to delve into the case to find out what really happened, and to wrestle with some of her own demons in the process. Two Truths and a Lie is a powerful story driven by intense, dogged research, told by a writer with great skill. This is sure to be one of the year’s best books in nonfiction crime. –Dwyer Murphy, CrimeReads Editor-in-Chief

Peter Vronsky, American Serial Killers: The Epidemic Years

(Berkley)The postwar period has come to be known, in some macabre circles, as the Golden Age of American serial murder. Peter Vronsky, one of the foremost chroniclers of modern serial killer stories, here narrows in on that period and frames the stories of these men, driven to kill in succession, as a kind of “epidemic.” Looking at their stories together offers insight into what drove them, but more than that Vronksy pieces together a theory of the unique American moment that gave rise to these terrible crimes. –DM

Sonia Faleiro, The Good Girls: An Ordinary Killing

(Grove)Sonia Faleiro is a narrative journalist with a talent for nuance and ambiguity, and in her new work of true crime, there are no easy answers—only hard conversations that the world must, and should, be having. The girls of Faleiro’s title, two teenagers growing up in a remote agricultural town in the state of Uttar Pradash, are murdered in the fields around their village after weeks of rumors and escalating tension. The Good Girls will not be a happy story. But it is an essential story. –Molly Odintz, CrimeReads Senior Editor

Russell Shorto, Smalltime: A Story of My Family and the Mob

(Norton)Growing up, Russell Shorto knew he was named for Russ Shorto, a mobster who ran a small criminal empire in Johnstown, Pennsylvania, but it wasn’t until recently that he started to get curious enough to look into the matter. Smalltime promises to be a lively journey into the illicit pastimes of factory towns in decades gone by, and the charismatic leaders of the underworld who lived to provide such entertainment. –MO

Keith Roysdon and Douglas Walker, The Westside Park Murders: Muncie’s Most Notorious Cold Case (The History Press)

In 1985 two teenagers, Kimberly Dowell and Ethan Dixon, were murdered in Muncie, Indiana. The killings spun out national headlines and a range of theories. (One of them involved Dungeons & Dragons, that 1980s boogeyman.) The community was rocked, and two reporters at The Star Press, Roysdon and Walker, were assigned to the story, which went unsolved for decades. They would occasionally check back in for new leads and angles, and after thirty years, with a new person of interest, they’ve performed their most detailed examination of the case to date. The Westside Park Murders is at once a vivid true crime account, but also something bigger, a portrait of a community bound in grief, reckoning with the kind of questions that won’t ever go away. –DM

Justin Fenton, We Own This City

(Random House)Fenton’s We Own This City is nonfiction writing at its most urgent and essential, as he unfolds the story of Baltimore’s Gun Trace Task Force, led by Sergeant Wayne Jenkins. The Task Force was put at the helm of the city’s efforts to get guns off the street and quell the violence that was bubbling up following the death of Freddie Gray in police custody. Instead, the force went on a crime spree of its own, stealing, skimming, intimidating, planting evidence, and generally turning itself into a dreaded band of corrupt stormtroopers. Fenton, a reporter at the Baltimore Sun, lays out in full and shocking detail the Task Force’s crimes and how they spread like a poison throughout a city that was already grieving. –DM

Alex Tresniowski, The Rope: A True Story of Murder, Heroism, and the Dawn of the NAACP

(Simon & Schuster/37INK)In this riveting true story, Alex Tresniowski tells the intertwined stories of a crusading reporter, an innovative detective, and a man unjustly imprisoned. When Marie Smith was murdered in a New Jersey resort community in 1910, town leaders immediately tried to pin the murder on a local Black man. Only thanks to the diligent efforts of a pioneering detective and a nascent civil rights movement was the true culprit discovered and the falsely accused suspect set free. You’ll read this in a night, I promise! –MO

Tori Telfer, Confident Women: Swindlers, Grifters, and Shapeshifters of the Female Persuasion

(Harper Perennial)Telfer’s portraits of women criminals are always clever and compulsively readable. Last time around she was looking at women who kill; this time the material has a little more zip and glamor, though no less crime. In Confident Women, Telfer profiles women scammers, swindlers, hustlers, and all around confidence artists down through the ages, offering up plenty of compelling theories, patterns, and insights along the way. –DM

Ioan Grillo, Blood Gun Money: How America Arms Gangs and Cartels

(Bloomsbury)The debate over gun control may flare most just after a mass shooting, but the everyday realities of gun violence are often intertwined with the realities of the drug trade and armaments manufacturing. In his new book, Ioan Grillo looks at the ease by which legally purchased weaponry makes its way into the illegal arms market, and the efforts of the gun lobby to derail any attempts at closing the loopholes that prevent effective arms control. –MO

-

When I tell people that I write cozy mysteries, the most common question I get is “Who are you and why are you knocking on my door at three o’clock in the morning?” The second most common question is “What are cozies?”

Cozy mysteries are fun, light-hearted adventures—with a side of murder. A reluctant sleuth in a quaint town filled with zany characters follows a twisty trail of suspects and clues to uncover the unlikely killer. Compared with their more hard-boiled mystery cousins, cozies have surprisingly little blood with their murders, and limited adult situations—with no strong language and no sex.

The first full-length cozy mystery appeared in the 1930s, featuring Agatha Christie’s Miss Marple. Christie’s books coined the phrase cozy, and set the stage for all the cozies to come—a highly intelligent, nosy, regular Josephine (I’d say Joe, but the main character is most often female) who solves crimes by relying on their shrewd wit and the local gossip, rather than digging into forensics like a Sherlock Holmes might. They have evolved with the times, but cozies endure as a popular—and fun!—genre.

Many cozy mysteries remain essentially unchanged since their creation nearly a century ago. Lilian Jackson Braun’s The Cat Who… books are an enjoyable series of a dozen mysteries, which other than having a notable male protagonist, are a perfect example of the genre. Dorothy St James’s The Broken Spine and Laurie Cass’s Gone with the Whisker are two more examples of fantastic embodiments of delightful traditional cozies—each with a brilliant female librarian with a mischievous cat and a penchant for solving murder in a charming setting.

However, the genre has expanded over the years to include edgier books, which deal with serious social issues, darker themes, or other real world subjects that straddle the line between cozies and traditional mystery. Leslie Meier’s Irish Parade Murder explores the topic of police use of force and the blue shield that protects them. Karen MacInerney’s Margie Peterson Mysteries deal with divorce and messy family issues, while her Dewberry Farm Mysteries touch on domestic violence. Then there’s the magnificent Charlaine Harris, who is best known for her Sookie Stackhouse The Southern Vampire Mysteries that were the basis of HBO’s True Blood. She also writes conventional cozies, such as the Aurora Teagarden series (which are featured on Hallmark Movies & Mysteries) in addition to edgier books that range from the Harper Connelly Mysteries where after a brush with death, the main character gets visions that help her locate dead bodies to the more darkly noir Lily Bard Shakespeare Series wherein the titular character has a mysterious, violent past.

As cozies grow in popularity, they might be adapted into movies, but some popular television shows align with the cozy genre as well. I’d argue that Scooby Doo is, at its heart, a cozy cartoon. My personal favorites are USA Network’s Psych (I found the pineapple!) and BBC’s Death In Paradise. The most well-known cozy mystery television show, however, is the beloved Murder, She Wrote, which ran for a dozen seasons and has spawned more than fifty popular spin-off companion novels, including Jessica Fletcher and Jon Land’s Murder in Season and the upcoming Killing in a Koi Pond by Jessica Fletcher and Terrie Farley Moran.

A new generation of cozies are appealing to a new audience. Abby Collette’s Ice Cream Parlor Mysteries, Mia P. Manansala Tita Rosie’s Kitchen Mysteries, and my own Brooklyn Murder Mysteries all feature Millennial main characters. Whereas traditionally, cozy heroines are often middle aged women, like Agatha Christie’s spinster busybody Miss Marple or Murder She Wrote’s Jessica Fletcher, these books trend younger. Manansala’s Lila Macapagal in Arsenic and Adobo, Collette’s Bronwyn Crewse in A Game of Cones, and Odessa Dean in my cozy mystery debut, Killer Content are all amateur sleuths in their early twenties, and all are characters that feel like they’d be fun to sit down and have a beer with when they’re not solving crimes.

Cozy mysteries have enduring appeal. Whether they are traditional, edgy, televised, or featuring a new generation, cozies will continue to entertain readers who enjoy a good mystery in a safe, comfortable setting with smart, lovable characters.

*

-